Tuesday night, for about the fourth time in my tenure, the Economics Department will show The Informant as a complement to our oligopoly case study in Economics 400. It should start at 9 p.m. in the Warch Campus Center Cinema. A good chunk of this text is a repost from last year:

The movie “comically” recreates the character of Archer Daniels Midlands (ADM) employee, Mark Whitacre, the principal informant in the notorious lysine price fixing scandal. Lysine is an essential amino acid used to fatten up hogs and broilers. If you mix it in with corn, you don’t have to spring for the relatively more expensive soymeal, or so I’m told.

Well, I’ll let deRoos (2006) characterize the market for us:

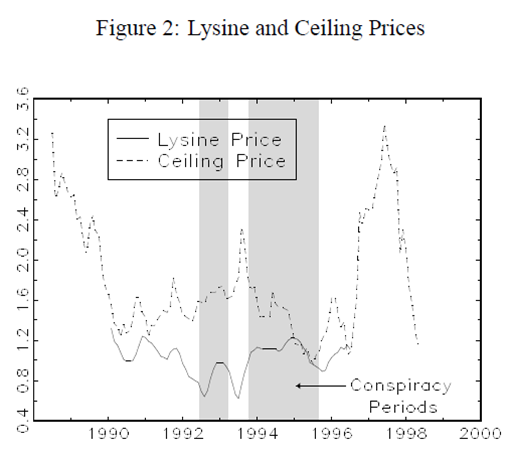

Through 1990 the market lysine market was dominated by three firms with prices (as you can see) somewhere north of $1 / lb. However, in 1991 ADM opened a massive production facility in Decatur, Illinois, doubling world capacity and pushing the price below $1 toward its (probable) marginal cost of $0.66 / lb.

Whitacre subsequently orchestrated a coordinated effort to fix prices among the four dominant producers (a CR4 of 95-97%), though there is some dispute as to what exactly happened. Nonetheless, price fixing is a per se violation of federal antitrust laws, so ADM was in pretty serious hot water as soon as Whitacre turned informant.

On the other hand, Whitacre was absolutely crazy himself. And the movie does a good job portraying the frustration and insanity of everyone involved in the situation as the events unfolded. It seems the best defense for ADM was to simply let Whitacre unravel and leave the prosecutors to deal with him.

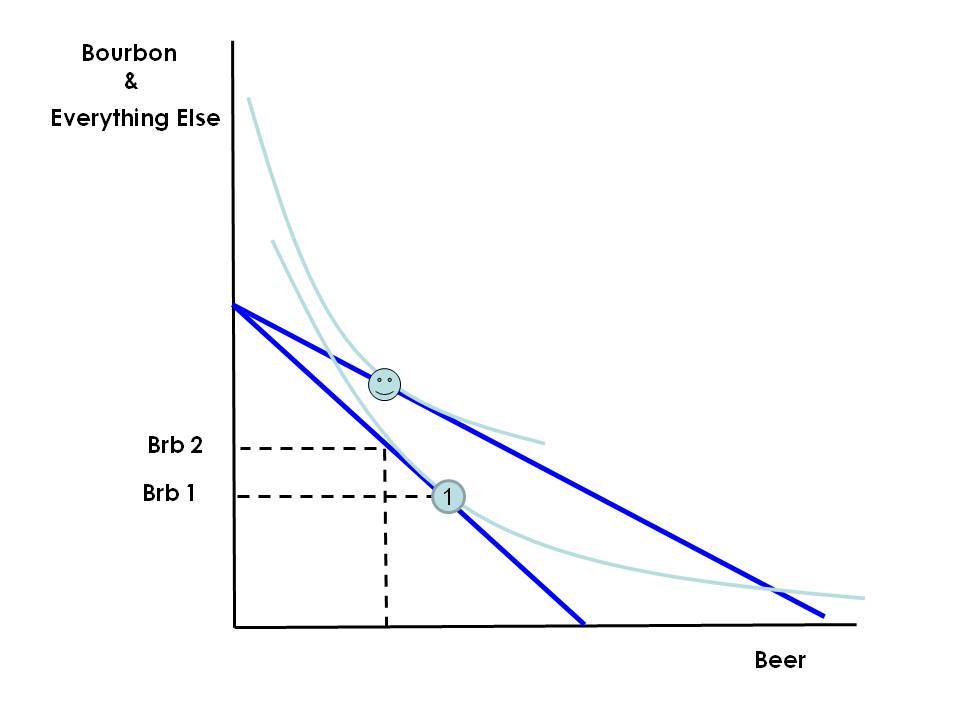

Meanwhile, the economics of the case spawned a rather, well, let’s call it a rather spirited debate in the academic literature over the length of the conspiracy and the damages done. These are well documented in the sources below, particularly John Connor and Lawrence White, who trade body blows over the appropriate theoretical model, the appropriate choice of the conspiracy period, and the proverbial “but for” price (that is, the price that would have prevailed “but for” the conspiracy). Connor is sort of the go-to guy on these issues and he was profiled in the Chronicle of Higher Education about three weeks ago.

A truly remarkable episode all around.

Pop some corn and mix in three parts lysine. We’ll see you there.

For further reading:

John M .Connor (1997) “The Global Lysine Price-Fixing Conspiracy of 1992-1995,” Review of Agricultural Economics, 19 (Fall/Winter), 412-427.

Nicholas deRoos (2006) “Examining models of collusion: The market for lysine,” International Journal of Industrial Organization, 24(6): 1083-1107

Lawrence White (2001) “Lysine and Price Fixing: How Long? How Severe? Review of Industrial Organization,18 (1):23-31

Alright, I still don’t have an accounting of our numbers (and I’m not even listed as an instructor), but it’s time to start talking about Wapshott’s Keynes Hayek book.

Alright, I still don’t have an accounting of our numbers (and I’m not even listed as an instructor), but it’s time to start talking about Wapshott’s Keynes Hayek book. This term’s economics read, DS 391 Keynes Hayek and Other Dead Economists, triumphantly kicks off this Thursday at 3:25 in Steitz 230.

This term’s economics read, DS 391 Keynes Hayek and Other Dead Economists, triumphantly kicks off this Thursday at 3:25 in Steitz 230.