When I have the occasion to make a sizable consumer item — a house or a car or even a big green egg — I often will borrow some money to finance the purchase. In the past few years, the person extending the credit invariably tells me that interest rates are historically really low and you should lock in now because rates have to go up in the future.

Really?

Yes, of course. How much lower could interest rates go?

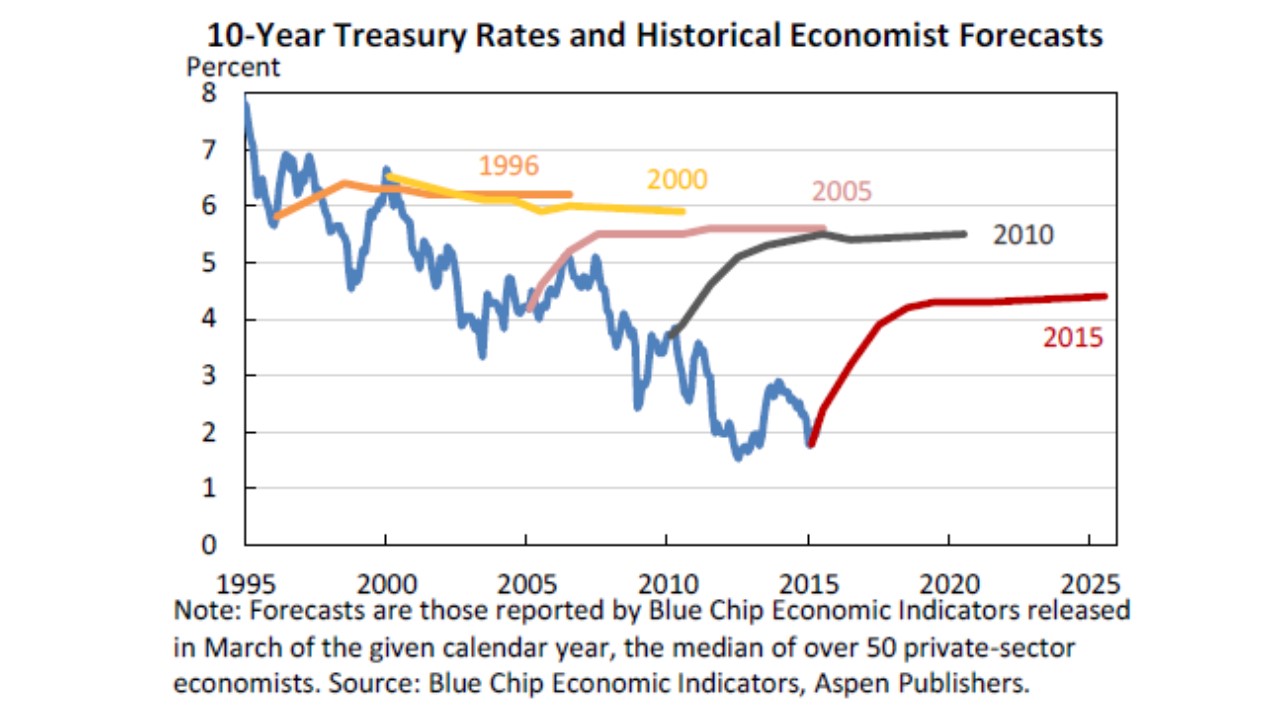

Well, I was reading a White House report on interest rates (from July 2015) that had a figure that shows yields on 10-year treasuries have been on a downward trajectory for a very long time, like 20+ years. Not only that, people who forecast such things have pretty much grossly overestimated future interest rates at pretty much every turn. In other words, for the past 20 years people have been saying that interest rates “have to go up” and for the past 20 years these people have been wrong.*

Yeah, sure, but how much lower can they go? It’s not like interest rates are going to go negative now, are they?

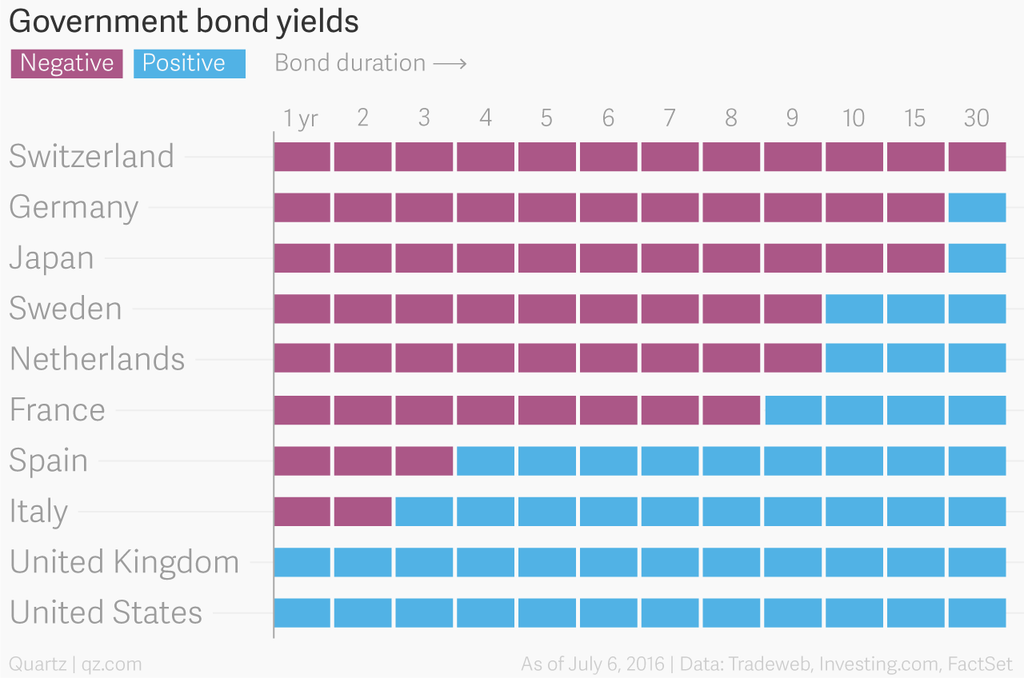

Well, actually, the bond yields for government debt around the world are increasingly going negative, with Quartz reporting that a third of all government debt worldwide has negative rates. People are paying governments for the privilege of having a nice, safe place to park their money.**

Right, right. Okay. But I’m not an investor and you aren’t a government. You don’t expect me to pay you to borrow money from me, now, do you? I mean, I’m already offering a discounted price and zero-percent financing for 60 months, plus this oven mitt here….

*In fairness, the earlier forecasts on this table just predicted interest rates to be rather flat going forward, which, incidentally, is a trick I learned from my time series professor — a pretty good estimate is whatever rates happen to be right now. If I knew where rates were going, (1) I certainly wouldn’t be telling you; and (2) I’d be enjoying a much different standard of living.

** Here’s “Everything you need to know about negative rates.”