That’s the classic question that Steven Shavell posed 25 years ago, and the debate over whether these two are potentially substitutes continues today.

That’s the classic question that Steven Shavell posed 25 years ago, and the debate over whether these two are potentially substitutes continues today.

The BP catastrophe has certainly brought more than its share of discussion on the issue. Paul Krugman weighs in on the side that the continuing spill is Exhibit A that liability is a failure the private sector needs a stern regulatory hand to guide it. Tyler Cowen frames the argument and takes Krugman to task on one point:

There is in fact an agency regulating off-shore drilling and in the case under question it totally failed.

Point, Cowen.

Of course, not all regulation is as inept as the Minerals Management Service (MMS) seems to be in this case. One problem is that MMS is charged both with regulating environmental and safety concerns AND is responsible for approving leases to the provide sector.

And, which do they choose? According to the Washington Post:

Minerals Management Service officials, who can receive cash bonuses in the thousands of dollars based in large part on meeting federal deadlines for leasing offshore oil and gas exploration, frequently changed documents and bypassed legal requirements aimed at protecting the marine environment, the documents show.

Emphasis is mine, though the point sort of jumps out at you, doesn’t it? But, it’s not like the appearance of financial impropriety is a new thing with the MMS. On the heels of the spill, in fact, President Obama recommended bifurcating the agency to mitigate the clear incentive compatibility problem.

Continue reading Liability for Harm Versus Regulation of Safety

The

The

… is certainly worth a barrel of cure. Instead of having these guys with big yellow boots (I thought only 4-year old boys ran around in public in galoshes out of season), perhaps it would pay to have more egghead types crunching data on safety risk. That was the message I gave in both my classes this week, as we sat down to read Shultz and Fischbeck’s “

… is certainly worth a barrel of cure. Instead of having these guys with big yellow boots (I thought only 4-year old boys ran around in public in galoshes out of season), perhaps it would pay to have more egghead types crunching data on safety risk. That was the message I gave in both my classes this week, as we sat down to read Shultz and Fischbeck’s “

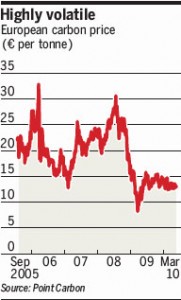

On the other side of the pond, there actually is a cap & trade system in place, and it is really all over the price. Carbon prices have ranged from €8 to €30, and the volatility can stymie long-term investments. In other words, there is likely to be an inverse relationship between carbon prices and the payoff to greener (or at least lower-carbon) energy sources. If investors don’t believe that carbon prices will be high, then green investments simply won’t be as attractive.

On the other side of the pond, there actually is a cap & trade system in place, and it is really all over the price. Carbon prices have ranged from €8 to €30, and the volatility can stymie long-term investments. In other words, there is likely to be an inverse relationship between carbon prices and the payoff to greener (or at least lower-carbon) energy sources. If investors don’t believe that carbon prices will be high, then green investments simply won’t be as attractive.

Well, the Department of Interior finally

Well, the Department of Interior finally  Lawrence alum, George B. Wyeth, will kick off the Povolny Lecture Series this Tuesday, April 20, at 7 p.m. in Science Hall 102. Mr. Wyeth picked up his B.A. from Lawrence back in 1973, notably serving as editor-in-chief of The Lawrentian. He leveraged his success here into a Masters in Public Policy at UC-Berkeley and a law degree from Yale. After a stint in the private sector, he joined the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1989 and is now the Director at the National Center for Environmental Innovation.

Lawrence alum, George B. Wyeth, will kick off the Povolny Lecture Series this Tuesday, April 20, at 7 p.m. in Science Hall 102. Mr. Wyeth picked up his B.A. from Lawrence back in 1973, notably serving as editor-in-chief of The Lawrentian. He leveraged his success here into a Masters in Public Policy at UC-Berkeley and a law degree from Yale. After a stint in the private sector, he joined the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1989 and is now the Director at the National Center for Environmental Innovation.