Story by Ed Berthiaume / Communications

Jake Frederick is drawn to disasters.

Natural and unnatural disasters. World-altering disasters.

He doesn’t wish for them or the pain and destruction they bring. But the Lawrence University professor of history is unapologetically fascinated by them, struck by the physical, cultural, and emotional recalibration that comes in their wake.

By the nature of his chosen profession, Frederick is usually focused on disasters from long ago, exploring how they altered life in the years, decades, even centuries, that followed, how they exposed inequities, and how they reshaped cultural norms. But right now, as we’re living through a global pandemic unlike anything seen in 100 years, it’s tough for even a history scholar like Frederick to keep the focus squarely on the past. When he was teaching his Disasters That Made the Americas class during the last Winter Term, he found conversations quickly shifting to the present as the spread of COVID-19 arrived in the Americas and the panicked hoarding of toilet paper signaled that life as we know it was about to change.

“I think in any class, whether it’s history or English lit or physics, when students see what they’re studying unfolding in the world they’re living in, they always find that very stimulating,” Frederick said.

“At the moment, this group of students is living through a more dramatic historic moment than I think students have in 100 years. There hasn’t been anything like this since the Spanish influenza outbreak in 1919 and 1920. Even the second World War, there was a home front, so you could always be away from where the disaster was happening. But in the case of the pandemic, it’s everywhere.”

It’s not just the pandemic, of course. The wildfires that burned through large chunks of the western United States in recent months, fueled by climate change that is rapidly altering the planet, provide even more fodder for the intersection of historical disasters and modern times.

Disasters That Made the Americas, a 400-level history course that is focused mostly on Latin America, is being offered again in the upcoming Winter Term, and Frederick said the pandemic and the wildfires will certainly be incorporated into the class discussions. How could they not? The current disasters can help inform the study of past disasters, whether illness, climate, war, or otherwise, and perhaps provide some insight into what lies ahead.

“History is interesting in and of itself,” Frederick said. “But I think we can learn a great deal from the modern moment. I wouldn’t dare say what will be the effect of COVID, because historians get very freaked out by the present tense. We need a good 10, 20 years to figure out what the impact will be. But as we look backwards and look at cholera outbreaks, the Spanish influenza outbreak, there is always something contemporary you can refer to in helping them understand the historical point you are talking about.”

Ricardo Jimenez, a senior biology and music performance double major from Barrington, Illinois, was in Frederick’s Winter Term class. He remembers Frederick talking about COVID-19 on one of the first days of class, in early January, two months before it would be declared a global pandemic. There were reports of a few thousand cases in Wuhan, China, and Frederick talked to his students about keeping a close eye on its spread.

In nearly every classroom session to follow, Frederick would start the discussion by giving an update on the virus as more news came out. He tried to contextualize the gravity of the moment and what might lie ahead based on lessons from history.

“We saw it go from a few thousand to tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands, and then eventually to other countries,” Jimenez said. … “I will never forget the day in which it arrived in the Americas and we had class the next day. Professor Frederick sat us down and said, ‘I don’t think we will be seeing each other next term.’ By this time, Europe was already on lockdowns.

“It was a very sobering moment to hear from a professor of disasters of human civilizations that this event that we were experiencing was a historical moment.”

Up close and personal

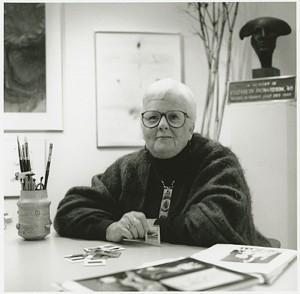

Frederick, a member of the History Department faculty since 2006 and co-director for Latin American Studies, comes by his fascination with disasters via experience. He fought forest fires in the 1990s before going to graduate school. The firefighting he did in Mexico piqued his interest in the history of that region, leading him to a Ph.D. from Penn State University with a focus on colonial Latin America.

“I’ve always found the history of fires really interesting and thought I could marry these things together,” Frederick said.

He’s on sabbatical during Fall Term as he works on a book about fires in 18th century Mexico. When the Disasters class returns in January, the students will, among other things, draw parallels between today’s ongoing disasters and those that dot the history of the Americas.

“Human beings care about the same things now that they cared about a thousand years ago,” Frederick said. “But it’s sometimes difficult for students to put themselves in that mindset. But with the kind of things they’re encountering right now, and with us looking at disaster as the focus of the course, we are going to have a lot of good conversations.”

Much of Frederick’s focus is on what comes next. What happens after a disaster alters life in a particular region? What inequities have been exposed? And what responses come from leaders and from the populace?

“To a certain extent, the disasters are the sexy hook that makes it very interesting to engage these moments, but the disasters themselves are isolated moments,” Frederick said. “What really is most compelling about them is the impact that they have.”

History suggests some of that impact is communal, at least in the short term. People—today’s anti-maskers notwithstanding—tend to rally together in times of disaster, trending away from the popular mythology that disasters cause societal breakdowns and lead to anarchy.

“In the wake of disasters, particularly very acute disasters, people tend to come together,” Frederick said. “In a big disaster, the first responders are always the neighbors, the nearest community. The rescue forces are there immediately. So, what you often see, after a big disaster, there is a big moment of community-building. And these things can do a lot, at least in the short term, to bring people together. Even if that’s not a lesson for the future, it debunks every disaster movie out there. In reality, people really do tend to provide a lot of help to their neighbors.”

The lessons of history

For all of our advanced medical technology, our radar systems, our smart phones, and the like, the disasters of 2020 provide a reminder that we are as subject to epic natural threats as humans were in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries—pandemics, wildfires, hurricanes, floods, earthquakes.

“When these things happen, there are very, very familiar consequences that tend to unfold,” Frederick said. “You find that certain parts of society will suffer the most. … What they tend to expose are pre-existing stresses that are in society, the pre-existing shortcomings of a society.”

The United States, for all its advancements, is no different, and the news cycle that is 2020 is making that clear.

“The responses (to disasters) tend to show the same thing,” Frederick said. “Wow, we have this disease coming, and it turns out that in the United States and across the world, health care is really unequally distributed. You might think that can be tolerated up to a point, but disasters tend to push those systems to the fracturing point.”

Lessons can be drawn, for example, from the cholera outbreak in Peru in the 1960s, which led to a reimagining of the country’s medical infrastructure.

“It was not necessarily, how are we going to prepare for the next cholera outbreak, but rather, how does this show us what is wrong with the system that exists now?” Frederick said. “And what it shows is that, disproportionately, poor people, people on the bottom of the socio-economic scale, were getting crushed by this disease. And there was a racial disparity. Indigenous people were getting disproportionately harmed by this disease.”

For Jimenez, learning how that has played out over and over again through history has given him perspective as he and his fellow students navigate the pandemic.

“I think studying past catastrophes helps you learn how events like these tend to unfold, who is really affected by them, and what the aftermath tends to look like,” Jimenez said. “I think the biggest takeaway from the course is really learning that the poorest in our society are those who suffer the most during any catastrophe. They are the most vulnerable but also the ones who are forgotten.”

These lessons from the past can inform the present. And vice versa. It’s what drew Frederick, the one-time firefighter, to the classroom in the first place.

“You can get a sense of relief and comfort from history,” Frederick said. “When you look at a disaster like COVID, you see that the world has gone through things like this before and we got out to the other side. It can be an awful process, and I promise this is going to get much worse before it gets better, but people have managed to get through this sort of thing and worse. Every single time, humanity has come out on the other side.”

Ed Berthiaume is director of public information at Lawrence University. Email: ed.c.berthiaume@lawrence.edu

—

Interested is readings from the Disasters class?

If Jake Frederick’s Disasters in the Americas class has piqued your interest and you want to read more, try these books that are part of the class:

The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster, by Jonathan Katz; New York: St. Martins Griffin, 2013. This book is about the 2010 earthquake.

A Paradise Built in Hell, by Rebecca Solnit; New York: Viking, 2009. The thesis of the book is that in times of urgent disaster people have a greater tendency to pull together than to turn on each other.

Floods, Famines, and Emperors: El Niño and the Fate of Civilizations, by Brian Fagan; New York: Basic Books, 1999. See chapters on the classic Maya collapse and the destruction of the Moche civilization.

On Main Hall Green With … Getting to know Jake Frederick, other Lawrence professors