Month: February 2012

Is 2013 a Ripe Time for Fundamental U.S. Tax Reform?

Yes, trumpets Lawrence Summers in today’s Financial Times. Presumably, anyone who pays any attention to the Washington scene knows Larry Summers. Just in case you haven’t been paying any attention for the past 20 years, the bullet point version of Summers’ CV might read as follows:

- Harvard Professor of Economics

- Chief Economist of the World Bank

- Secretary of Treasury under President Clinton

- President of Harvard University

- Chief Economic Adviser to President Obama

Few people – economists, policy analysts, or politicians – defend the current tax codes filled with huge inequities in both horizontal and vertical directions (as argued here.) Tax “loopholes,” tax expenditures (CBO estimates), or societal preferences – if you care to be generous – reduce taxable income by at least $800 billion per year. Stated differently, if all special provisions (i.e., everything but the personal exemption) of the U.S. tax code were eliminated, income tax revenue would rise to at least $2 trillion and cover about two-thirds of the estimated U.S. Federal deficit for 2012.

So what makes 2013 so special? Summers gives a variety of intriguing answers including the following:

- President Bush’s tax cuts expire

- Congress faces its mandated sequester of $1.2 trillion spending for the next decade

- Congress must again vote on the legally binding Federal borrowing limit

- Fundamental reform can happen in the year after a Presidential election

- The last serious tax reform took place in 1986 (when a Republican President reached agreement with a Democratic legislature)

As Summers argues,equity, efficiency, and budgetary reasons all dictate that we need to fundamentally reform the tax structure. The longer we wait, the more difficult the choices will be. If (when?) the rest of the world decides it no longer has a voracious appetite for U.S. Treasuries, our choices will be much more painful. He argues, and I agree, a good place to start would be the recommendations of the Simpson-Bowles Commission appointed by President Obama, which unfortunately in my view, he chose not to back vigorously.

Please Do Not Try this at Home, Especially My Home

In our continuing series on moral hazard I ask you this: what is the opportunity cost &/or reservation price of your off hand?

Thirty-four-year-old Gerald B. Hardin faces six charges, including mail fraud for a 2008 incident in Sumter County where a man’s hand was cut off with a pole saw.

Federal indictments state that Hardin and another person used a saw to intentionally cut off the hand of a third person in an insurance fraud scheme. The indictment says the men submitted claims under a homeowner’s insurance policy and three accidental death and dismemberment polices.

It says the men received more than $670,000.

So the guy with the missing hand must have a reservation price pretty far south of $670,000, as the perpetrators split the ill-gotten booty three ways. You have to hand it to these guys, though, coming up with this sleight-of-hand to outwit their insurance providers.

Well, almost

I have to ad-mitt that the article doesn’t say that it was his off-hand. But, on the other hand, I bet the payout for the dominant hand is higher, but that is just an off-the-cuff conjecture.

Are Cracks Developing over Chinese Water Usage?

I’m not the resident expert on water usage in China, but there is something unsettling about recent reports out of Shanghai.

Slated to be the China’s tallest building upon completion, the 632-meter tall Shanghai Tower conveys stability, if not permanence.

The ground under it, however, is another story.

Spectators were intrigued in mid-February when a giant 8-meter long crack appeared in the asphalt near the tower. The crack was a reminder of Shanghai’s shifting and sinking ground, which scientists say makes the city vulnerable to rising sea levels.

And Shanghai is not alone. China’s Ministry of Land and Resources recently reported that the ground is sinking under more than 50 cities. The culprit is the overuse of groundwater, the ministry’s Geological Environment Department Deputy Director Tao Qingfa told Caixin.

When residents consume too much groundwater, water pressure underground depletes and causes the soil to shift and sink, Tao said. Beijing, Tianjin, Hangzhou and Xi’an are all sinking in certain places as a result, he said.

I saw this over at foreign policy scholar Walter Russell Mead’s blog. He seems to think the crack is a metaphor for fractures in China more generally, as rifts develop between rich and poor, urban and rural, local and national, authority and spontaneity. As Professor Mead puts it, “Sooner or later, something will give.”

Rapid industrialization doesn’t come easy.

Economics of Innovation in the New “Pamphlet” Era

This week seems to be innovation week for me, as I am reading two short books on the heels of The Great Stagnation. Reading these pieces, I can’t help but get the feeling that the economics profession is hurtling into a blog-soaked, pamphlet-era frenzy. First up for Econ 100 is Alex Tabarrok’s Launching the Innovation Renaissance (review here), where Tabarrok makes a case against patents, holds out promise for prizes, and makes a plea for broad educational reform in both primary and secondary education. For the Reading Group crowd we have Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee’s Race Against The Machine: How the Digital Revolution is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy, and with a subtitle like that, who needs a description?

So for those of you who have read one and need a primer on the other, here you go:

As a warm up to Renaissance, here is Tabarrok giving his TED lecture. Here’s a bit on education. (If you follow all the links at Marginal Revolution, you can pretty much read the whole book).

Here are Brynjolfsson and McAfee summarizing their argument in The Atlantic. See also Professor Finkler’s recent plug.

I’ve read both and recommend both. We’ll see what my Econ 100 students think. Thought provoking all around.

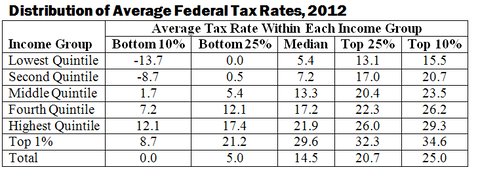

The Federal Income Tax is Both Horizontally and Vertically Inequitable

In today’s Economix blog, Bruce Bartlett argues that our Federal income tax burden violates two fundamental economic principles. Although the tax system on average is progressive (in the sense that households in higher income groups pay on average proportionately higher tax rates than those in lower income groups), it violates both horizontal and vertical equity. Horizontal equity requires that people with the same income and circumstances should pay the same tax rate. Vertical equity usually is interpreted to mean that those with greater ability to pay (higher income and all else equal) should pay higher tax rates. As the chart below, taken by Bartlett from the Annual Report of the Council of Economic Advisors Report for 2012, shows numerous inequities exist.

The chart should be read horizontally. For those in the middle quintile (40-60% levels) of income, the average income tax rate ranges from 1.7% to 23.5%. For those in the top 1% bracket, the range is from 8.7% to 34.6%. Clearly horizontal inequity exists within each quintile and vertical inequity exists across quintiles, since many in higher quintiles pay a lower rate than many in lower quartiles.

These results arise because different incomes are taxed differently. Those whose incomes are attributed to labor face higher rates than those whose income can be attributed to capital. This is especially pertinent for investment fund managers who are paid in capital gains rather than salary. Not only do they pay a lower income tax rate than those with the same level of income but they also avoid some payroll taxes assessed against wages and salary income.

Any serious attempt at tax reform should directly confront these inequities not only for “fairness” reasons but because the income tax system provides strong incentives that distort the allocation of labor and human capital toward favored categories, many of which benefited greatly over the past decade.

Man vs. the Machine. Man is Losing

This week many of you are reading Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s book Race Against the Machine. The authors make reference to a September 28, 2011 Wall Street Journal article by Kathleen Madigan entitled “It’s Man vs. Machine and Man is Losing.” Madigan provides the chart below to illustrate the relative growth of equipment and software in comparison with payroll employment since the trough of the recession in June 2009.

As I have previously argued here and here, Madigan notes how the relative price of labor compared to capital is consistent with the pattern shown in the above chart. Again, job creation clearly is quite difficult if the incentives are perverse.

Keynes, Cowen, Brynjolfsson, McAfee & Capitalism

Here’s the update from the reading group.

On the subject of big, fat profits in the financial sector, you might consider visiting some of these pieces. On the subject of big, fat incomes in the financial world, Cowen offers up a simple theory on why so many smart young people go into finance, law, and consulting. Adding fuel to this fire, “Mr. D” sends me this helpful blog post from Ezra Klein, arguing that Ivy Leaguers head to the Street because that’s where they get their “real” education. Do you buy that? And, in a similar vein, “Mr. P” wants to know why Americans don’t elect scientists.

We left off yesterday with the open question of what the best-case scenario is for market economies moving forward. Where are the big productivity gains going to come from? What type of work is to be done? Is manufacturing dead or alive, or does it even matter? (See Professor Finkler’s previous post). Has John Stuart Mill’s concern about the inevitable decline in radical breakthrough inventions finally come home to roost?

And, this opens the door for next week’s book, Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s Race Against The Machine: How the Digital Revolution is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy. There are a couple of secondary sources on this, as well, including pieces from The Economist and The Wall Street Journal.

By all rights, this term’s 391 DS reading group should be titled Keynes, Cowen, Brynjolfsson, Backhouse, Bateman, McAfee, and Capitalism, but that doesn’t quite roll of the tongue, does it?

Nor would it fit on your transcript.

Manufacturing Matters or Does It? Two Democratic Former CEA Chairs Battle it Out

In his State of the Union Address, President Obama highlighted the importance of providing special treatment for U.S. manufacturing through tax breaks and other forms of direct support. In a February 4th op-ed piece in the New York Times, Christina Romer, the first Chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) finds the arguments for such special treatment less than compelling. In response, in a February 10th New York Times Economix blogposting, Laura D’Andrea Tyson, the Chair of President Clinton’s CEA, makes the case for why manufacturing deserves such support. This blog posting summarizes their arguments. Read the full articles for yourselves and respond by indicating which argument you find more compelling.

Professor Romer makes the following points in arguing that special treatment for manufacturing is unnecessary.

- No market failure specific to manufacturing exists.

- Innovation takes time to commercialize, thus special treatment makes sense; however, innovation is far from limited to manufacturing.

- National defense needs must be met but such needs do not map easily onto manufacturing. The problem, of course, becomes identifying in some objective way which industries (firms?) are essential to the national defense.

- Manufacturing industries have not been great job creators, as the share of employment tied to manufacturing has declined markedly in the past 30 years. Technology and rapid productivity growth have led to not only a reduced need for workers but an increased need for more high skilled workers.

- Improved income distribution is not well served by a specific focus on job creation in manufacturing. It is better served by direct attention to policies that will raise the skill levels of the population in a way that matches the needed capabilities.

Professor Tyson begs to differ. She highlights the recent increase in manufacturing jobs as well as the need to strengthen U.S. competitiveness in manufacturing. Specifically, she makes the following points:

- The U.S. economy needs to be rebalanced towards export production, and manufacturing goods make up 60% of the exports of goods and services.

- Manufacturing jobs are highly productive and provide relatively high compensation to workers; thus, we should encourage such job creation as a way to raise the average level of worker compensation.

- Manufacturing companies play a key role in innovation. They employ the majority of scientists and engineers in the U.S. and cover 68% of business R & D (research and development) dollars.

- Increased manufacturing activity will assist in keeping R & D in the U.S. rather than see it outsourced along with lower skilled employment.

Both Romer and Tyson support extension of the R & D tax credit and efforts to improve the skills of the American workforce. Clearly, they disagree, especially given current and prospective budgetary pressures, how narrowly focused these policies should be. With whom to you agree?

Keynes, Cowen & Capitalism Meets in Steitz 230

We have found a home for Econ 391, and it is in Steitz 230. We will see you over there at 3:25 on Thursday.

We began with Tyler Cowen’s The Great Stagnation, and in our first meeting we took a first cut at these questions:

1. What is the thesis of the book?

2.What does “the great stagnation” mean? What is stagnating? “Great” compared to what? Is the title a play on another “Great” episode do you suppose?

3. How is “stagnation” measured? Do you buy this means of measurement?

4. What does Cowen suggest is the cause of the great stagnation? How does he support his case? Can you think of alternate explanations?

5. What is Cowen’s remedy for the great stagnation, if any? Does it suggest a pro-market, get-out-of-the-way response? A more muscular federal policy response? New institutions? What?

6. Make a list of Cowen’s arguments that you buy and arguments that you don’t buy.

This week, we take on the “companion piece” from The American Interest, “The Inequality that Matters.” It’s hard to think about the future of capitalism without thinking a bit about what inequality is and why it is (and isn’t) important.

It seems an opportune time to point to the Financial Times’ recent in-depth debate, Capitalism in Crisis. There is some excellent material in there, and we will take a look at some of this when we get to the Backhouse and Bateman book.

Can’t Beet these Profit Margins

This past week in 100 we tackled the unusual welfare economics and the effects of price controls. For introductory economics courses, rent control and minimum wage policies generally serve as the dominant examples of controls that mean well, yet have perverse impacts. But I’ve always had a soft spot for the U.S. sugar program, which continues to surprise and astonish.

As you probably don’t know, but might suspect, the average U.S. citizen consumes about 140 lbs of sweeteners per year, about half coming in the form of sugar and the other half in the form of some sweet corn goodness.

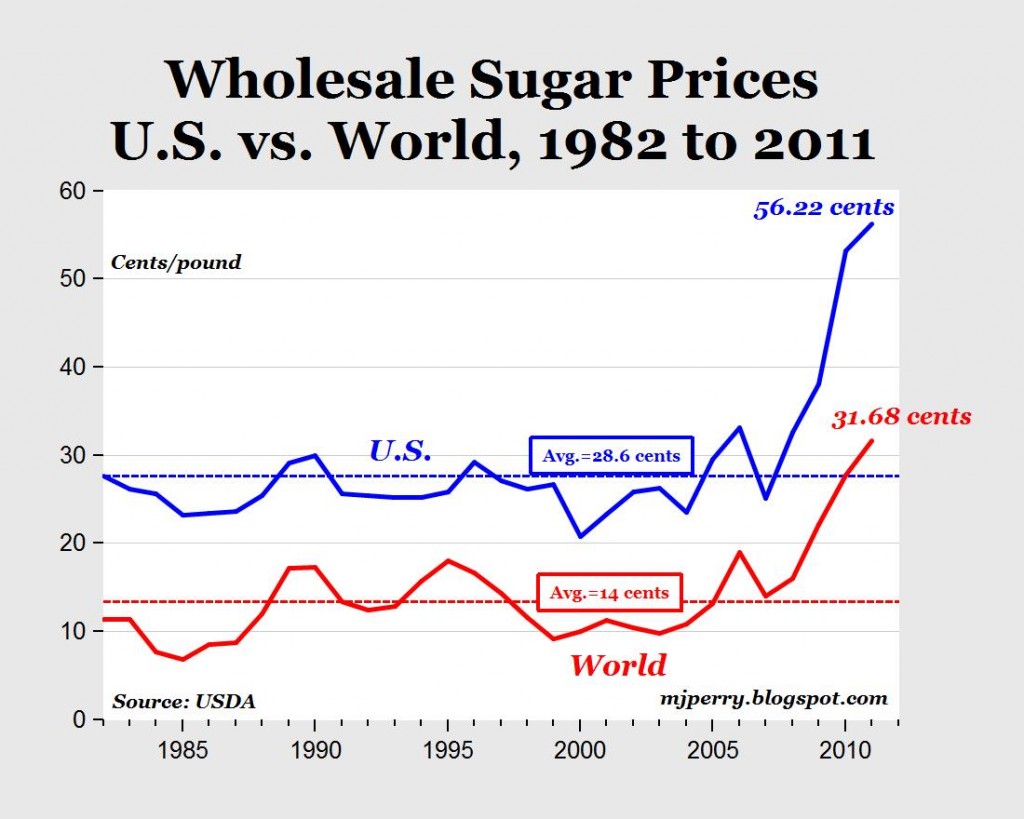

Because of import restrictions, however, U.S. consumers pay a rather steep markup over world price. In class I cited a 2010 article where U.S. prices were about $0.35 per pound compared with $0.20 on the world market. If you take $0.15 per lb. times 70 lbs. times 300 million people, you’re starting to talk about real money.

But on a trip over to Mark Perry’s blog, I see that sugar prices have gone absolutely bonkers in the past two years. Perry has a nice figure that shows the markup is now more like $0.25 per pound, meaning that sugar producers are now really going to the bank. Perry estimates that with the markup, U.S. consumers pay about $3.5 billion more for sugar than they would absent the quota. Although that is certainly a tall number, on a per capita basis it only comes to about $10-$12 per person.

On the other hand, the U.S. sugar producers pocket a healthy chunk of that $3.5 billion.

In one of the all-time great sound bites, Judy Sanchez from U.S. Sugar Corp. said sugar policy has “zero cost” to taxpayers and offered up this line:

Face it: Sugar is given away for free in restaurants, where they charge you for water, they charge you for an extra slice of cheese on your hamburger. The sugar is so affordable that it’s given away for free. That’s because American sugar policy works.

Do you suppose sugar would still be “given away for free” if the U.S. price was cut in half tomorrow?

UPDATE: For some background, here’s a Congressional Research Service report — usually readable, often helpful.

Could tiny organisms carried by house cats be creeping into our brains?

Crazy, awesome, completely plausible:

Jaroslav Flegr is no kook. And yet, for years, he suspected his mind had been taken over by parasites that had invaded his brain. So the prolific biologist took his science-fiction hunch into the lab. What he’s now discovering will startle you. Could tiny organisms carried by house cats be creeping into our brains, causing everything from car wrecks to schizophrenia? A biologist’s science- fiction hunch is gaining credence and shaping the emerging science of mind- controlling parasites.

In other words, Reading Period continues…

Winners, Losers, and Microsoft Update

Our Senior Readers have forged through Liebowitz and Margolis’s Winners, Losers, and Microsoft, so terms like “increasing returns,” “network effects,” “serial monopoly,” and “lock in” are now rolling off their tongues. I am very impressed with how the group has embraced the book and how fluid the discussions have been. I will count this one as a winner.

So, as a follow up, we have an absolutely remarkable data point from Business Insider (via Mark Perry) that the iPhone is now bigger than Microsoft. (See here for background to the big pies).

The iPhone.

Bigger than Microsoft.

That is remarkable.

Microsoft just plain missed these markets (iPhone and iPad). And Apple created them. And it turns out that, at least for now, they are much more valuable and lucrative markets than the ones Microsoft dominated.

The other mistake Microsoft made, one that ultimately could be far more devastating, is that it became obsessed with the wrong competitor.

For the past decade, Microsoft has obsessively targeted Google as Enemy No. 1, blowing more than $10 billion trying to compete with Google’s amazing search engine.

Plenty to chew on here.

One observation: This does not seem to be Bertrand or Cournot competition, does it?

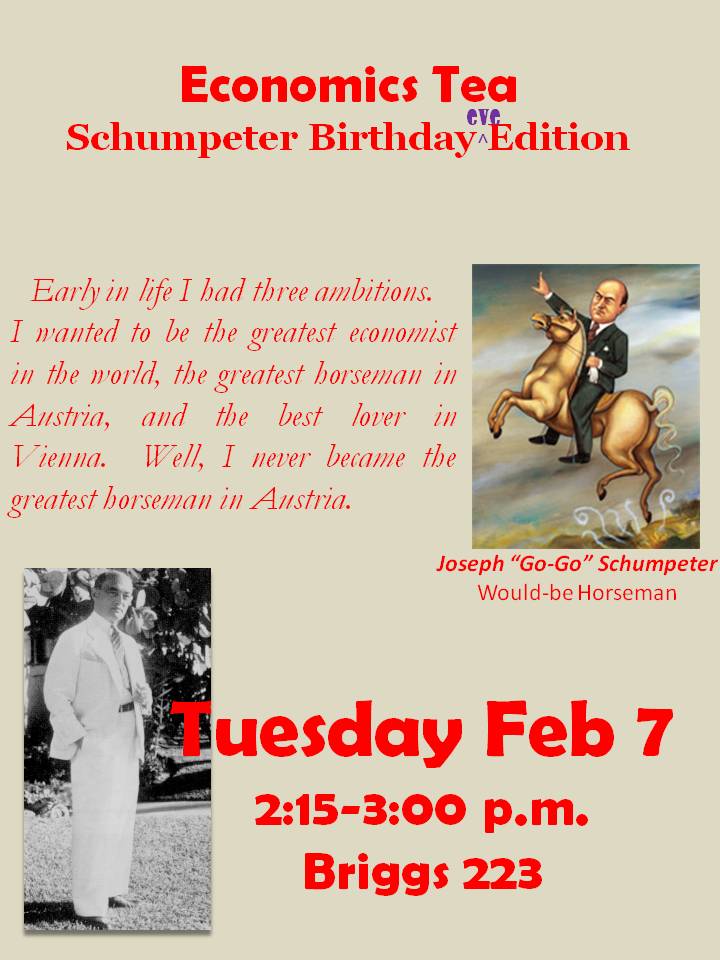

Econ Tea this Tuesday

Keynes, Cowen, & Capitalism Update

The first session rolled along pretty well, I thought, with 14 students and four faculty participating. I was pleased that everyone had something to say, and I hope you will make an effort to talk about this outside of the group. Our next meeting is February 16 at 3:30, and I am still looking for a regular room to meet.

For next time we will continue our discussion of The Great Stagnation, and in particular we will talk about whether we believe the central thesis. One synopsis of the thesis is that there are three pieces of bad news: there are fewer innovations, the yield on innovations has declined, and innovations are not resulting in high-quality employment gains. We talked a little bit about this idea of raising the status of scientists and what that might look like. In that vein, we might take a look at one of Cowen’s recent blog posts: a simple theory of why so many smart young people end up in finance and law. I’m not sure how to square one with the other.

On this point, I might add, Schumpter was optimistic that norms could change:

the prestige motive, more than any other, can be molded by simple reconditioning: successful performers may conceivably be satisfied nearly as well with the privilege—if granted with judicious economy—of being allowed to stick a penny stamp on their trousers as they are by receiving a million a year (CS&D, p. 208).

The discussion of science inevitably got at the nature of American higher education, an area that moves at a glacial pace, but might be amidst a revolution (who are you going to believe?). On this topic, Larry Summers’ offers his take on the future of education. I have been thinking about this for a while in terms of how we can do better down here on Briggs 2nd, and am wondering what the take of our new president will be.

We will also forge ahead with Cowen’s “The Inequality that Matters,” from The American Interest. It’s hard to think about the future of capitalism without thinking a bit about what inequality is and why it is (and isn’t) important. We read this in Econ 275 last term and I think it went over quite well.