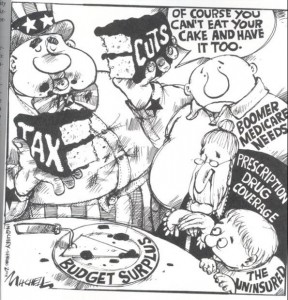

In a recent article in Forbes, contributor Nick Shulz asks what the “new normal” for economic growth in the U.S. will be. On one side, we find Tyler Cowen (The Great Stagnation) and Robert Gordon (“Is U.S. Economic Growth Over?…”) arguing that the technological low hanging fruit have been picked and that the future will feature economic growth similar to what existed before the industrial revolution (that is, well below 1% per year.)

In a recent article in Forbes, contributor Nick Shulz asks what the “new normal” for economic growth in the U.S. will be. On one side, we find Tyler Cowen (The Great Stagnation) and Robert Gordon (“Is U.S. Economic Growth Over?…”) arguing that the technological low hanging fruit have been picked and that the future will feature economic growth similar to what existed before the industrial revolution (that is, well below 1% per year.)

On the other side of the debate, Race Against the Machine authors Bryjolfsson and McAfee and authors of the new volume The 4% Solution, published by the Bush Institute, suggest that the future will be brighter than the past.

Which do you believe? On which future would you bet? Why?