In this New York Times blog posting, Uwe Reinhardt, one of the most eloquent economists I have ever heard speak, tweaks Congress for its ignorance of the notion of opportunity cost and for a lack of understanding of the fundamental principles of policy making. Furthermore, he provides a link to a marvelous discussion between Milton Friedman and a University of Chicago student that took place as part of the Free to Choose series in the 1970s.

Author: Merton Finkler

2010 Lawrence Grad Gives TEDx talk.

Murtaza Edries, who graduated with a major in economics in 2010, recently gave a talk on locally generated political and economic change in Afganistan at a TEDx Kabul conference. Since graduation, Edries has worked for several organizations in Afganistan that have been involved in reform projects. In his talk, he addresses the importance of developing reforms that derive from local needs and local initiative. He is a candidate for a Fulbright scholarship. He is very excited about the potential reforms in Afganistan including those that might arise from the presidential election now in progress.

The Greatest Period in World History

Morgan Housel at The Motley Fool lists the 50 reasons we’re living through the greatest period in world history (free registration may be required), and here are the first three (for the rest see here):

1. U.S. life expectancy at birth was 39 years in 1800, 49 years in 1900, 68 years in 1950, and 79 years today. The average newborn today can expect to live an entire generation longer than his great-grandparents could.

2. In 1949, Popular Mechanics magazine made the bold prediction that someday a computer could weigh less than 1 ton. I wrote this sentence on an iPad that weighs 0.73 pounds.

3. The average American now retires at age 62. One hundred years ago, the average American died at age 51. Enjoy your golden years — your ancestors didn’t get any of them.

See Louis CK talk about “Everything’s amazing and nobody’s happy.

How (Not) to Lie With Benefit-Cost Analysis

In the current issue of The Economists’ Voice, the former Chief Economist for the US General Accounting Office Scott Farrow addresses the uses and abuses of Benefit-Cost Analysis (BCA), also known as Cost-Benefit Analysis. He highlights some common abuses and ways to avoid them. Below you will find a few samples. His short article (only 6 pages) contains many more.

Lie #1. Be selective in your impacts and values

Response: Ask “Are there major elements missing, or too many present in this analysis?”

Lie #2. Confuse the baseline

Response: Ask “What is the basis of comparison? Is that reasonable and is it (almost always) the same for both benefits and costs?”

Lie #3. Count jobs entirely as a benefit

Response: Ask “Are new jobs just being taken away from other location that is included in our calculation?”

I encourage you to read the details and not to forget the advice of British economist Alan Williams who concluded in a marvelous paper in 1972 entitled “Cost-Benefit Analysis: Bastard Science? and/Or Insidious Poison in the Body Politick? that

CBA is not the way to perfect truth, but the world is not a perfect place… I prefer the philosophy embodied in the answer Maurice Chevalier is alleged to have given to an interviewer who asked him how he viewed old age: ‘Well, there is quite a lot wrong with it, but it isn’t so bad when you consider the alternative.’

Life’s Too Short for the Wrong Job

Check out these ads from a German job-hunting website (jobsintown.de) . Here’s a sample to wet your taste.

The FOMC (Federal Reserve Open Market Committee) Meets at Lawrence

No, this is not April Fool’s Day. Tomorrow’s Money and Monetary Policy class will host Lawrence alum and Federal Reserve

Bank of Minneapolis’ First Vice President Jim Lyon (9 – 10:50, Briggs 217). During the first hour, Lyon will discuss the Dodd-Frank Financial Reform Act passed in 2010. He will detail how far along the implementation process is as well as what we can expect to happen.

During the second hour, Lyon will put on his “Ben Bernanke hat” and chair a shadow meeting of the FOMC. Students in the class will present the views of the other members of the Board of Governors of the Fed as well as those of the bank presidents of the 12 regional Federal Reserve banks.

You are welcome to attend these awesome proceedings.

What Will Happen if the Treasury Runs Out of Cash as a Result of Reaching Its Borrowing Limit? The President Will Have to Break the Law. The Only Question is Which Law.

In yesterday’s Economix blog, former Reagan and GHW Bush administrator Bruce Bartlett addressed the possible options. Below is a crisp summary of the details. Read his full post for more.

1. The debt limit is public law.

2. Appropriations (passed by the Congress) are also public law.

3. Entitlement programs (such as Social Security and Medicare) are public law.

4. The Prompt Payment Act, which requires that obligations be paid when they come due, is public law.

Result: something has to give.

5. Treasury can’t easily determine which bills to pay or not pay. It does not have sufficient information to determine priorities. Various departments and agencies would need to set such priorities. This, however, would be difficult since it would take time to do so and many staff members required to provide input have been furloughed.

6. To enable prompt payment, Treasury has established processes “to make payments when they are due, whether the cash is there or not.”

7. As a result of point 6, obligations are likely to be paid in order of due date as cash becomes available.

8. If 7 holds, some bondholders will experience a delay in receipt of payment, but this means the security would be classified as “non-performing.” As Bartlett puts it.

Treasury would now be in default, and defaulted securities cannot be traded, accepted by the Federal Reserve as collateral, or held by money market funds. In a note published on Oct. 5, Goldman Sachs said money managers are forced to dump Treasury securities before October 17 to avoid being stuck with securities that could not be traded.

9. Section 4 of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution provides a rationale for the president to override debt limit legislation.

10. President Obama has said, on numerous occasions that he will not use the authority granted by the Constitution to get around the debt limit set by Congress.

Result: At best, uncertainty predominates. At worst, Treasuries are not accepted as collateral by many financial managers and organizations. I’m not sure which game theory structure applies – Help, Professor Galambos. Some have characterized the situation as a game of chicken – who will give in first. My conclusion is that it is a negative sum game in which the magnitude of the losses in the resultant payoff matrix swamps the few available positive results.

Conclusion: This is a game that should be avoided. Will it be avoided? I hope so.

Health Insurance Exchanges: Something Both Liberals and Conservatives Could Love?

In an opinion piece in the Harvard Business Review today, Henry Aaron (the well known economist, not the Hall of Fame baseball player) argues that conservatives and liberals should both support the health insurance exchanges that form the core of the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare.) He notes that conservatives decry the tax and mandatory provisions of the act and that liberals prefer “Medicare for all”, but concludes that both groups fail to see that the core elements they desire are contained within the act.

For conservatives he posits the following:

Conservatives want people to be free to choose the insurance plan that best matches their preferences. They want insurers to compete with one another based on price and service. They are convinced that if individuals can shop freely for the plans they want and insurers must compete actively for their business, everyone will gain: customers will get coverage that matches their preferences, and insurers will become more cost- and quality-conscious than they now are. Conservatives also recognize that many people will need financial help if they are to afford health insurance, and they have embraced such aid.

For liberals he argues:

Liberals want universal coverage. While they accept competition, they believe that regulations are also necessary to hold down the growth of health care spending and promote the adoption of improved modes of delivering care… By design, the exchanges will intensify competition by requiring insurers to offer the full range of plans to customers. By providing software and counseling, the exchanges will help consumers make informed comparisons among these offerings…To do a good job the exchanges have at hand a number of important regulatory powers along lines that liberals have long endorsed.

He concludes that if the exchanges become open to all and do a reasonable job of encouraging informed choice then

…most businesses may well be glad to rid themselves of administering a vexatious form of compensation that has nothing to do with their main business activities. If and when that happens, the exchanges will have become the instrument for realizing the conservative dream—free individual choice and tough, head-to-head competition among health insurers.

Yes, there are numerous “ifs” in the story, but what’s the alternative? J.D. Kleinke put it best in his 2001 book Oxymorons: the Myth of a U.S. Health Care System:

There is no U.S. health care system. what we call our health care system is, in daily practice, a hodgepodge of historic legacies, philosophical conflicts and competing economic schemes. Health care in America combines the tortured politicized complexity of the U.S. tax code with a cacophony of intractable political, cultural, and religious debates about personal rights and responsibilities. Every time policymakers, corporate health benefits purchasers, or entrepreneurs try to fix something in our health care system, they run smack into its central reality: the primary producers and consumers of medical care are uniquely, stubbornly self-serving as they chew through vast sums of other people’s money.

In the Long Run, We’re All Dead or Consume Now, It’s Patriotic

British economist John Maynard Keynes is well known for the first half of this statement. Both President Bush and President Obama have made comments consistent with the second half of the statement. Presumably, such opinions are related to idea that more immediate economic growth is good, at least when the growth rate is well below its recent history.

As Casey Mulligan points out in two recent Economix Blog entries (here and here), such views confuse correlation with causality. In short, expanded consumption need not lead to increased growth. Just ask the PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain.) Sustainable economic growth requires the generation of income and wealth upon which sustainable consumption must be based. Such growth requires some degree of postponed consumer gratification which can generate savings that can be use to improve (or increase) physical capital, human capital, or ideas. In terms of sustainable economic growth, Mulligan rejects Obama Advisor Jared Bernstein’s view (previously stated by others including President Richard Nixon) that “we are all Keynesians now.”

Enterprise Proposals by Students in Entrepreneurship and Finance

Come one, come all to hear budding entrepreneurs present their proposals to a group of “sharks”, as in the venture capitalists who review business proposals on the ABC program Shark Tank.

The presentations will take place Tuesday, May 28th and Thursday, May 30th from 2:30 – 4:00 in Cinema. See details below.

Tuesday, May 28th

Time Enterprise Entrepreneurs

2:30pm ReactSTART Pat Vincent & Luke Barthelmess

3:00pm Café Crossfit Tanner DeBettencourt & Alex Brewer

3:30pm 4.0: The Place to Be At Aimen Khan, Minh Nguyen, James Maverick & Nathan Nichols-Weliky-Fearing

Thursday, May 30th

Time Enterprise Entrepreneurs

2:30pm Kefir Mania Max Randolph, Tony Darling & Carl Byers

3:00pm Ivory Conscience Gaming Babajide Ademola, Yuto Sawaki & Will Evans

3:30pm Care for Caregivers Jake Zimmerman & Kabindra Dhakal

Will the US Economy Continue to Grow at 20th Century Rates? Robert Gordon and Eric Brynjolffson Square Off in a Lively Debate

This week Lawrence will be hosting a TEDx conference on re-imagining liberal education. Thanks to Professors Galambos and Gerard, and a few other colleagues from other departments, this live discussion will be video streamed for all of us to watch.

Earlier this month, another TED conference took place. This one featured economist Robert Gordon (Northwestern) and Eric Brynjolffson (MIT). Some of you will be familiar with the arguments. Those who took Capital and Growth last year read Gordon’s paper on the headwinds that will drive economic growth back to the level experienced prior to the first industrial revolution in the 18th century in England. Gordon believes that our most productive innovations are behind us and innovation will be insufficient to enable us to sustain the 2% per capita real growth of the 20th century.

Some of you may recall the discussion we had in one of our reading groups of Brynjolffson and McAfee’s book, Race Against the Machine. In his TED talk, Brynjolffson explains why innovation is far from over and that we have the potential to continue the rate of growth of economic prosperity that we experienced in the 20th century. Of course, the challenge, as he puts it is: “can we race with the machine?”

View both talks as well as a follow-up debate between these two economists here.

Inflation Is Your Friend!

This view point has been recently propounded by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his protege (puppet?) Haruhiko Kuroda, selected to be in charge of the Bank of Japan. Japan is tired of two decades of stagnation and falling or at least not rising prices. Mr. Abe has pushed for a 2% inflation target and Mr. Kuroda will provide $77 billion worth of monthly bond purchases to achieve that goal. If that’s not enough, will more be forthcoming? Is a little good and more better?

Inflation as a cure for economic ills is not new. In fact, check out this 1933 video on the how inflation is good for everything and everyone. Clearly, proponents of Neo-classical macro beg to differ. Those in Econ 320 will have a chance to sort out the winners and losers. Indeed there will be losers, as we know that there is no free lunch. Who will the winners be?

1. lenders or borrowers

2. savers or consumers

3. labor or management

4. bond holders or stock holders

5. renters or buyers

6. government officials or Wall Street tycoons

Place your bets now or maybe just guard (cover?) your assets.

Whatever else you do watch the video? It’s a hoot.

Hans Rosling on Global Health and Economic Development

Some of you may recall Hans Rosling’s TED talk entitled “The Magic Washing Machine” which uses his famous Gapminder software to characterize past and prospective economic development. Well, he’s done it again. Rosling’s talk last summer explains why it makes little sense to split the world into Developed and Developing. Using his stellar graphical tools, he makes numerous fascinating comparisons you won’t want to miss. If you have 20 minutes to spare, watch his talk here.

America’s Future: A Look on the Bright Side

Last Friday, Motley Fool’s Morgan Housel highlighted several positive aspects about the American economy.

1. The most beautiful de-leveraging on record.

Despite a 6% drop in employment from the beginning of the 2007 – 2009 recession, US employment loss has been less than most other industrialized countries in the last 35 years.

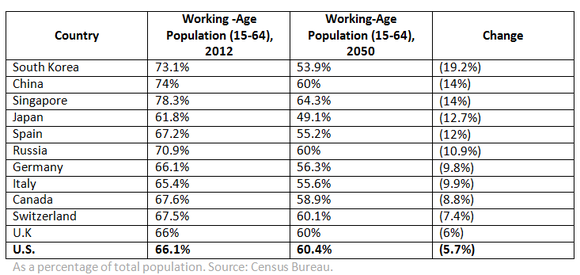

2. America has the best demographics of any developed country in the world.

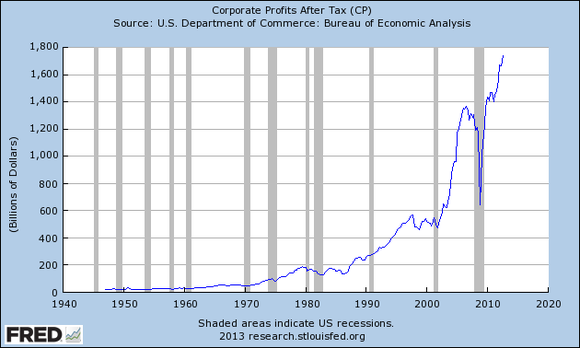

3. America’s businesses have never been more profitable.

4. We have abundant and increasingly cheap energy.

For example, natural gas in the US sold for $3.30 per million BTU in contrast with $10.60 in Europe and $16.70 in Japan.

Perhaps, in contrast with Robert Gordon’s vision (see here and here) , the best is yet to come.

The Fiscal Cliff Averted?

Yesterday, Congress passed legislation designed to avoid the strictures Congress enacted in the summer of 2011 to enable the United States government to borrow in excess of the existent debt ceiling. These provisions would have allowed the income tax cuts enacted in the George W. Bush era to expire as well as imposed spending limits on defense and discretionary non-defense spending.

There are numerous provisions in yesterday’s bill, summarized by the White House here. The Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimates the increased revenue from the bill to yield $62o over 10 years, far short of the 4 trillion dollars some estimate will be need to generate a sustainable level of debt. Furthermore, the debt ceiling and expenditure components of the “cliff” will remain subjects of political debate for at least the next two months when further action will be required. In short, we have “kicked the can down the proverbial road” again.

Bruce Bartlett, in a New York Times Economix posting yesterday, offers little in the way of enthusiasm regarding the political feasibility of making serious headway in addressing prospective budget deficits now and in the near future. His argument parallels the time inconsistency argument that earned Edward Prescott and Finn Kydland the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2004.

The Congress that raises taxes and cuts benefits will suffer politically, while the benefits of lower deficits will accrue to future Congresses.

He goes on to argue that

Historically, what has moved Congress to enact big deficit-reduction packages was the prospect of quick improvement in terms of inflation, growth and interest rates. Given that deficit reduction today is very unlikely to improve any of these in the near term, deficit hawks lack any real payoff from a grand bargain.

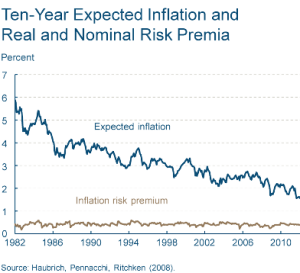

Inflation has been low and stable as has expected inflation.

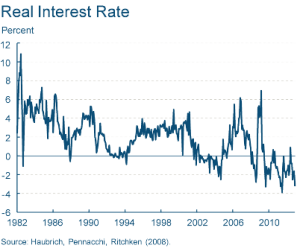

Even though expected inflation has been stable or declining for the past decade, real interest rates for treasuries (see chart below) – market rates minus expected inflation – has been negative for much of the past decade with the exception of the brief positive values in 2005 – 2007 and with expected deflation in late 2008. If real interests are negative, the crowding effects of public sector borrowing are non-existent; thus, the cost of running deficits has not “spooked” the markets. Of course, permanent negative real interest rates are not sustainable since few lenders will continue to offer their savings in exchange for reduced future consumption.

In the famous song from The Lion King, Hakuna Matata – there are no worries or no problem. Of course, such attitudes last only as long as those who lend money to the US government continue to do so. As Reinhart and Rogoff argue persuasively in This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, this time is not different. Financial excesses and repression eventually must be paid for. We just don’t know when or how severe the price will be.

ZIRP: The New Free Lunch? Don’t Bet on It.

The Federal Reserve Bank of the US has followed a zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) since fall 2008. It has employed a variety of mechanisms to lower not only overnight loans between banks (the Federal Funds rate – its usual target) but also to lower the entire yield curve. (See the details at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.) Previous postings here and here have addressed some of the costs of this approach.

Yesterday’s Financial Times contains some historical evidence consistent with the idea that ZIRPS are not free. John Plender argues that experience in Japan over two decades indicates that very low interest rate monetary policy did significant structural damage to the Japanese economy. In addition to creating a very low cost of capital, excessive monetary ease tends to lock-in the existing industrial structure or as he argues

“…from the Austrian perspective of Von Mises, Schumpeter, and Hayek, the Japanese bubble that burst in 1990 fostered economic distortions they dubbed ‘malinvestments’ – credit driven investments in real capital that prove loss making when a credit bubble implodes.”

As a consequence, Japan impeded “creatively destructive” economic activity since “zombie” companies were kept alive by cheap credit that was not available to new entrants. Capital allocation became very distorted; hence, many profitable opportunities were foregone and low return (perhaps even negative return) activities remained in existence.

Of course, that was Japan. Not the U.S. That couldn’t happen here, could it?

Economic Recovery: How Slow Has Our Recovery From the 2007-2009 Recession Been?

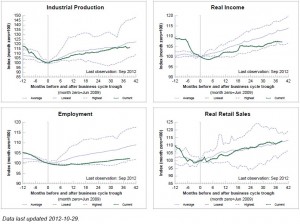

Much political debate – more appropriate described as hot or even toxic air – attempts to address how poorly the economy has recovered from what Reinhardt and Rogoff call The Great Contraction. As noted in Professor Gerard’s recent post, R and R argue– as they have done many times before – that recoveries from balance sheet or financial crisis recessions are much slower than those related to “garden variety” declines in aggregate demand. So what does the current recovery look like? One way to answer this is to view the four major indicators that the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Business Cycle Dating Committee uses to identify the beginning and ending points for recessionary and expansionary periods. Fortunately, our friends at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis have done all the hard work. As can readily be seen below (or more clearly here), industrial production and real retail sales have grown roughly in line with the average of past recessions. Real income started to grow similar to past history, but for the past 18 months growth has slowed markedly. The employment growth pattern, however, has shown the least responsiveness to the medicinal help provided by the Federal Reserve and other governmental policies. This suggests that “financial crisis” related recessions require both more time and different policies than demand deficient recessions not induced by too much debt. I will have more to say about why in future posts.

Impending Change in Chinese Leadership

Want to learn more about (rare) peaceful transitions of power in communist countries? Come to Mark Frazier’s lecture. Want to understand how China sees its own future? Come to Mark Frazier’s lecture. Want to know the relationship between communism and capitalism in China? Come to Mark Frazier’s lecture.

Want to learn more about (rare) peaceful transitions of power in communist countries? Come to Mark Frazier’s lecture. Want to understand how China sees its own future? Come to Mark Frazier’s lecture. Want to know the relationship between communism and capitalism in China? Come to Mark Frazier’s lecture.

Former Lawrence Professor, Mark Frazier, presently co-director of the India China Institute at the New School in New York City, will give the second Povolny lecture this fall tomorrow night at 7:30 PM in the Wriston Auditorium. The title for his talk is “Who is Xi? Knowns and Unknowns in China’s Political Future. For more information see Frazier talk_ Oct 2012

Regulating Wall Street: Did We Go Too Far?

Lawrence alum Elijah Brewer will address the above question in the next Economics Colloquium. It will take place next Monday, October 8th, in Steitz Hall 102 at 4:30. We encourage all to attend.

Brewer characterizes what he will argue as follows:

The causes of the financial crisis of 2007-09 are many and varied. Indeed, the crisis may be viewed as the product of a perfect storm. This address will discuss many of the popular causes of the U.S. crisis and enumerate their more important sins. It then presents the traditional way we like to think about commercial banks, and how that had changed leading up to the financial crisis. Indicators of stress in the financial system, and commercial banks in particular, are presented. What you will see is that many of these indicators were flashing red well before regulators got their hands around the problem. I will argue that it was not the lack of regulation, but a lack of will by regulators to enforce the rules that were already on the books. Thus, the government’s and Congress’s desire to regulate Wall Street is mis-placed. The banking industry does not need more regulation for the regulators to ignore when it’s convenient for them to do so, but we need a greater will by regulators to enforce the regulations that they do have. I will conclude by offering an assessment of the Dodd-Frank Act.

Simplicity vs. Complexity : It’s Not That Simple

Everyone knows that the Dodd-Frank law passed in 2010 to regulate the financial industry is incredibly complex. As those who took Money and Monetary Policy last fall learned from alum Jim Lyon, it will take years just to write the implementation provisions. Furthermore, these provisions will be influenced significantly by those (especially in the banking industry) whose behavior will be affected.

Andrew Haldane, in the most recent Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank symposium in an article entitled “The Dog and the Frisbee”, argues that such complexity is far from optimal in an economic environment in which uncertainty prevails. He uses the concept of uncertainty in the same way that Frank Knight and John Maynard Keynes did almost a century ago; that is, situations in which assessing the probability of different outcomes is quite low and that risk cannot be easily measured and therefore, hedged against. Haldane argues for simple rules, such as existed under the Glass-Steagall Act which forbids the mixing of commercial and investment banking.

In a recent blog entry on the EconoMonitor, Ed Dolan analyses this argument in terms of Goodhart’s Law, which suggests that as soon as a particular indicator becomes an explicit policy variable, it loses its predictive power because economic agents change their actions in response to expectations of the authorities using this indicator for policy action. Some of you might recall this as a variation of the Lucas critique of traditional monetary and fiscal policy actions.

All of the above is prologue for our next Economics Colloquium to be held next Monday. Our visitor, 1971 Lawrence alum, Elijah Brewer, will address the topic “Regulating Wall Street: Did We Go Too Far?” Be sure to come to his talk at 4:30 PM, Monday, October 8th in Steitz Hall 102.