Bring your thoughts. Bring your questions and your thirst for knowledge to EconTea today at 4:30. Your favorite faculty members are excited to interact with you on the topics of the day.

Author: Merton Finkler

Stephen Colbert Testifies on Immigration

Don’t miss Colbert’s testimony before Congress on immigration. The guy clearly understands markets.

Global Competitiveness

The U.S. is number 4 according to the global competitiveness survey just released by the World Economic Forum. It dropped from second to fourth in the past year. Switzerland, Sweden, and Singapore (is there something about S?) lie above the US. What’s behind these rankings? Should anyone care? See today’s Financial Times Lex column for both an editorial opinion on the survey and for a link to the full report. The website for the report contains profiles of each country as well as informative commentary about its meaning.

Krugman vs. Rajan on the Causes of and Responses to US Economic Stagnation

Paul Krugman rejects the claims that Raghuram Rajan makes about why the US entered the financial crisis. Furthermore he argues that the cause is not particularly important and that more macroeconomic policy stimulus is needed until the US returns to pre-recession levels of employment and GDP. Rajan argues that such stimulus is partly the reason why the crisis was created and that fundamental reform is required.

Cafe Hayek provides links to both articles in a recent posting.

Raghuram Rajan responds to criticism from Krugman and Wells. Much of his response will be familiar to Cafe Hayek readers but it is convenient to have all of Krugman’s mistakes about the housing bubble assembled in one place.

The Yuan Also Rises?

For a variety of reasons, Chinese economic policy makers resist pressures to allow the yuan (or renminbi) to rise against the dollar. On this side of the great pond (i.e., the Pacific Ocean), politicians (see H.R. 2378 Ryan-Murphy bill) and many economists clamor for explicit pressure that “forces” the Chinese to allow the yuan to appreciate. What would happen if the yuan were to rise markedly against the dollar? Several observations are worth making.

1. Much of the trade deficit that exists between the US and China arises from the sale of final goods. The value added by Chinese firms in these goods, however, is rather small. So what? If the yuan rises, it means that Chinese firms will be able to purchase intermediate goods more cheaply than at present; thus, the decrease in the cost of Chinese goods in yuan terms will counter the rise in the exchange rate and limit the change in prices to American consumers.

2. It’s not clear that changes in the nominal exchange rate drive large changes in purchasing. For example, the Japanese yen was forced to appreciate against the dollar in the late 1980s. Such a rise has had limited impact on trade with Japan. The U.S. runs trade deficits with virtually all of its major trading partners. This is a natural outgrowth of diminishing savings relative to (tangible) investment over past three decades.

3. On a related point, Gillian Tett, in today’s Financial Times argues that the Japanese experience with a rising yuan could be replicated in China. Unless China reforms its banking and financial system in a way that decentralizes the allocation of capital, it may suffer the economic stagnation that Japan has suffered for the past two decades. Cheap capital, centrally allocated, tends to yield excess capacity in politically sensitive industries. I have heard this argument on many occasions in China. If China’s economy were to suffer a long period of weakness, demand for US, European, and Asia goods would diminish, not rise.

4. The iron triangle or impossible trilogy restricts countries from having a) open capital markets, b) a fixed exchange rate, and c) independent monetary policy at the same time. Different countries, based on the depth and breadth of their domestic capital markets and their social time preferences, as well as their desire to attract capital, make different choices. China chooses some combination of capital controls and limited monetary independence along with a fixed exchange rate. The US and Europe, with much more developed capital markets, choose to allow exchange rates to float. Small countries, dependent on world trade and world interest rates, such as Hong Kong and Estonia, forgo independent monetary policy. There is no right choice. Each country manipulates the tools it believes give it the highest level of economic welfare.

My advice to US policy makers: be careful what you ask for.

Dana Fellowship at Ronin Capital

INVITATION

An information session regarding the Fellowship will be held on Saturday, September 25. The session will begin with lunch in the Schuman Dining Room beginning at 12:00 noon followed by an information session from 1:00 until 3:00 p.m. in the Hurvis Room of the Warch Campus Center. Mr. Larry Domash ’81, who is a partner with Ronin Capital (a world – wide proprietary trading firm based in Chicago) and Imtiaz Khan ’09 will be facilitating the session. To sign up for lunch and/or the information session, please stop by or call the Career Center (920 832 6561). Registration deadline is Wednesday, September 22.

HISTORY

During the summer of 2009, Ronin Capital hired Imtiaz Khan ’09 to work on a research project examining, in part, the causes and opportunities associated with the 2007 – 2008 “US financial markets crisis.” The success of this project led to the establishment of the James Dana Fellowship for graduating Lawrence University students.

GOING FORWARD

For each of the next five years (2011 – 2016) Mr. Domash ’81 will be hiring 1 student annually from LU to serve as a Dana Fellow. Each Dana Fellow hired will work on an empirical project. While the background and formatting work for the study will be performed in Chicago – some of the empirical data gathering will take place in NYC and London.

The finished project will be published for distribution to clients/ consultants / academics – for review and feedback. The LU grads chosen to be Dana Fellows will also receive training in research techniques and have the opportunity to observe how their research translates to trading for approximately 1 year. The individual will receive full salary and bonus during their work with Mr. Domash as well as a reference for placement. Upon completion of the project, Mr. Domash will work with the individual and help in all aspects of placement in an investment advisory or Wall Street style trading firm – if desired.

During 2011 – 2012, the named Dana Fellow will be working on a research project examining the 2010 Sovereign Debt Crisis in Europe and will encompass both a statistical and abstract examination of European Government finances as well as policies relating to fiscal and tax policies. It is envisioned that the study will try to provide a statistical substantiation to Keynesian economic theory..

The James Dana Fellowship was established with a dual purpose: 1.) to create viable empirical research leading to new trading bond/equity trading strategies at Ronin Capital; 2.) to establish a mentoring and networking community for Lawrence graduates and undergraduates within the trading and Wall Street finance industry. Part of the requirements of the fellowship is to help Lawrence undergrads gain insight into the trading community and to “give back to the University” by donating time.

Who are they looking for to be Dana Fellows?

- Self starters

- Students who have excellent communication skills and are fluent in operating all aspects of the Microsoft Office product suite.

- Students that enjoy research.

- Students that can work by themselves and who are comfortable in a team environment.

- Students genuinely curious about the Sovereign Debt Crisis of 2010.

- Students that can ask any question and not be embarrassed

- Students that have enjoyed their Lawrence experience.

- Most of all the ability to learn.

Wells Capital Management Positions

The Investment Risk Management team at Wells Capital Management is currently recruiting college seniors for two Associate Investment Risk Analyst positions. The ideal candidate would have excellent problem-solving skills, a strong math background with a preference for computer science, and an interest in the financial markets. Strong communication skills and the ability to work effectively as part of a team are also very important. See Kathy Heinzen in the Career Center or me for details.

The application deadline is September 30; so take action if you are interested.

Deloitte Touche Plans Hiring Spree

Today’s Financial Times indicates that Deloitte Touche Tommatsu plans to hire 50,000 workers per year over the next years. Take advantage.

10 Mistakes That Start-Up Entrepreneurs Make

For this piece, I refer you directly to Rosalind Resnick’s guest column in today’s Wall Street Journal. For those of you who have taken an entrepreneurship course, I’ll highlight numbers 9 and 10.

9. Not having a business plan

10. Over-thinking your business plan

The Worst May Not Be Behind Us

Two days ago, I posted James Hamilton’s blog entry on Friday’s GDP numbers and suggested that the 1.6% growth in GDP was not as depressing as it might seem. Primarily, I noted that inventory growth had slowed and imports had risen. The latter might be viewed as demonstrating renewed economic strength whether the imports reflect increased household consumption and household income (which they do) or increased business purchases of intermediate inputs (which they also do.)

In today’s Financial Times, economists Carmen and Vincent Reinhart summarize their address given last week at the Kansas City Feds’ annual symposium which features central bankers from all over the world. The Reinharts warn us that financial crises of the sort we are emerging from do not generate robust rebounds.

Such optimism, however, may be premature. We have analysed data on numerous severe economic dislocations over the past three-quarters of a century; a record of misfortune including 15 severe post-second world war crises, the Great Depression and the 1973-74 oil shock. The result is a bracing warning that the future is likely to bring only hard choices.

But if we continue as others have before, the need to deleverage will dampen employment and growth for some time to come.

Although aggressive use of fiscal and monetary policies may be necessary to avoid the risks of economic depression, they are no substitute for changes in expectations and economic structure required to find a stable long term economic growth path. Attempts to avoid such “creative destructive” will only deepen the cost of the inevitable adjustment that must take place.

Not that Depressing!

On Friday, the second report on 2nd quarter GDP was released; it displayed GDP growth at 1.6% instead of 2.4%. The decline came from a downward revision in inventory buildup and an upward revision in imports. James Hamilton in his Econobrowser posting argues that the report suggests that the economy is still moving upwards though at a modest pace. It does not suggest a double dip recession. Hamilton provides some nice charts and tables to tell the tale. Check it out.

What Should Central Bankers Do To Address PLOGs?

Obviously, to answer this question begs another: What’s a PLOG? or perhaps: Should we view central bankers as plumbers? PLOG, a term coined by IMF economist Andre Meier, refers to Persistently Large Output Gap or positive deviation between potential GDP and measured GDP. The big concern raised by the LEX column in today’s Financial Times regards whether central bankers should worry about a deflationary double dip recession. As Lex puts it:

“The supposed PLOG-effect creates a dilemma: the Scylla of deflation or the Charybdis of extraordinarily easy monetary policy.”

Based on Meier’s study of 25 episodes in advanced economies, Lex argues that recessions slowly reduce inflation rates and generally stop prior to serious deflation. Therefore, central bankers should not become preoccupied with such a threat. Indeed, attempts to further stimulate economies such as ours with monetary policy is likely to be ineffective (or to use the proverbial idea: it’s like pushing on a string.)

I find the final sentence of the opinion piece particularly instructive.

“And while a PLOG may not create deflation, it can only amplify the grim economic effects of over-indebtedness, whatever policies central bankers adopt.”

Journal of Economic Perspectives

For a limited time (I think), the American Economics Association is providing complimentary access to articles in The Journal of Economic Perspectives. Each issue of the journal provides a series of short papers on one or more topics of common interest as well as other articles of interest to those who want access to the state-of-the-art economic thinking without needing to wade through the sophisticated mathematics or economic arguments that require graduate level training. The Summer 2010 issue, for example, devotes one set of articles to approaches to economic development and a second set to President Bush’s “No Child Left Behind” program. Sample early; sample often.

Good Intentions, Bad Policy

In today’s Economix Blog, Edward Glaeser reminds us of a paradox that William Stanley Jevons posed in the 1800s. When public policy makes something more efficient (such as automobiles or electrical appliances), people may respond by expanded their use of the underlying product (gasoline or electricity). For example, CAFE standards, which seek to increase the gasoline efficiency of automobiles by requiring a higher miles per gallon standard for cars, may actually induce us to drive more. It all depends upon how much cheaper it is to drive, and the price elasticity of demand. We need to be sure that the adopted policy serves its ultimate objective, for example, to reduce an externality such as congestion or carbon emissions. As Glaeser puts it,

“Well-designed policies, like a congestion tax or carbon tax, can reduce social problems by getting the right sort of behavioral response; interventions that create an offsetting behavioral response can push the world in the wrong direction….The real lesson is that a change in the effective price of a commodity leads to a behavioral response, and, in some cases, that response can be so strong that it reverses the desired effect. As America considers new policies in public health, environmentalism and financial regulation, Jevons is as relevant as ever.”

Should Efficiency Be Economists’ “Holy Grail?”

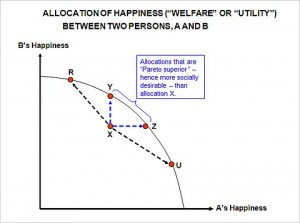

In today’s New York Times Economix Blog, Uwe Reinhardt poses the central question: “Is ‘More Efficient” Always Better?” In answer to the question he provides the basic definitions one would confront in an introductory economics course – including appropriate references to Pareto – and proceeds to point out that some efficient points, such as R and U, are not necessarily better than some inefficient ones (any in the region bounded by X, Y, and Z).

He then proceeds to link efficiency with optimality, which becomes his point of contention.

“One suspects that the term optimal came into widespread use among economists as a marketing device to promote their normative propositions based on efficiency. But as Professor Arrow warns his colleagues on this point:

A definition is just a definition, but when the definiendum is a word already in common use with highly favorable connotations, it is clear that we are really trying to be persuasive; we are implicitly recommending the achievement of optimal states.

Alas, it gets worse. Astute readers will have figured out by now that literally every point falling on the entire solid curve in the graph must be “Pareto optimal” by the economist’s definition of that term, not only those falling on line segment Y-Z. That circumstance makes the economist’s use of the word optimal even more dubious.”

In my view, Reinhardt stops in the wrong place. Rather than “dis” the term efficiency, he could differentiate between Pareto efficient (all points on the concave curve bounded by the two axes and called in this case the Happiness Possibility Frontier or HPF) and Pareto optimality (which employs Pareto’s notion that, at these points, to make someone better off, another person must be made worse off.) So what’s the point? Actually, there are two points to be made.

1. For any point (or allocation) below the HPF, that is any Pareto inefficient allocation, there exist Pareto improvement possibilities, and economists should encourage taking advantage of such.

2. Once on the HPF, Pareto optimal allocations depend upon social preferences, about which economists have no unique judgment to contribute; however, each such social choice judgment does yield consequences with opportunity costs (foregone choices) that can be identified. Stated differently, all Pareto efficient points are candidate points to be Pareto optimal under some set (of sometimes very curious) social preferences.

To conclude, the notion of efficiency is not a vague term, and it does reflect a value free standard. In my view, one can claim that for any Pareto inefficient allocation, Pareto improvements exist. Efficiency, however, says nothing about the optimal choice until preferences – in this case comparison of A’s vs. B’s happiness – is made. Furthermore, economists should encourage those making such social preferences to be transparent rather than hide them in 2000 pages of legislation.

Deficient Aggregate Demand vs. Structural Faults

Macroeconomists debate feverishly about the causes of a stagnant U.S. economy. Some such as Paul Krugman argue that demand deficiency (a Keynesian diagnosis) requires very aggressive monetary and fiscal policy until the economy reaches its potential. Others, such as Edmund Phelps in an August 6th opinion piece in the New York Times argue that our macroeconomic problems are structural and not related to deficient demand. He argues that

“The [aggregate demand] prescription will fail because the diagnosis is wrong.” He goes on to argue that our focus on reviving demand “lulls us into failing to think structural.” He cites such structural deficiencies as “short term” incentives employed by established businesses and financial managers, poor incentives for innovation, and a lack of inclusiveness in income gains that have arisen over the past two decades. Phelps suggests a number of policy actions that might be taken to put the US economy back on a dynamic path essential for prosperity and growth. In short, we need to move beyond short term demand stimulus to long term incentives to innovate. In his view, “the economy needs a bit of ingenuity.”

Manufacturing is the Answer But to Which Question

Recently, Andrew Grove (former CEO of Intel) and a number of policy makers have claimed that we need to keep our manufacturing sector vibrant as a way to sustain national economic security. In today’s Financial Times, Columbia University economist, and perennial Nobel Prize candidate, Jagdish Bhagwati contests that claim, and notes that we already subsidize American manufacturing in many ways. Furthermore, he argues that such efforts have not been good value nor have they been the best way to increase employment or innovation. He concludes as follows:

“In policy, sometimes Gresham’s Law operates – with bad policies driving away good ones. With no good argument in its favour, a preoccupation with manufacturing industries threatens yet one more example of such a perverse outcome. By promoting manufacturing of all kinds (as can be expected as the sector’s lobbies get down to work) at the expense of more innovative and dynamic service sectors, precisely when America is faltering in its recovery from the crisis, this unhelpful fascination promises to inflict gratuitous damage on an economy that can ill afford new wounds.”

Which Planet Are We On? Indeed!

Given the information in the statement, I would call it a “Capital Loss” special. Nothing has been said about what happened to the general level of prices or about the purchasing power of the asset. Without such information, one can say nothing very interesting about the change in the price of one specific asset. It’s certainly possible that the price of an asset (call it shares of Lehman or Enron stock) can fall with or without inflation or deflation. I can’t tell what the purpose of the example is; hence, as Professor Gerard points out, Planet Money needs help.

They may need as much help as the US Senate who rejected Fed Board of Governor’s nominee Peter Diamond because he allegedly was not a macroeconomist.

Ah, those discerning folks who man our legislature.

Incentives Matter. All Else Is Commentary Or Is It?

Economist Steven Landsburg recently argued that economics can be summarized in two words “incentives matter.” He further noted that “all else is commentary.” Tim Harford, author of The Undercover Economist, argues in today’s Financial Times that he accepts the notion that incentives matter, but “the devil is in the details.” He chides himself and other economists (as well as bankers and policy makers) for not understanding the painful relevance of such detail. In short, forewarned should mean forearmed.

The Wall Street Saga as Shakespeare Might Have Told It

In today’s Financial Times, John Kay crafts a Shakespearean characterization of recent life on Wall Street. See if you recognize all of the characters. If you want the details, read (or listen to) Andrew Ross Sorkin’s Too Big to Fail. This one definitely falls in the “tragedy” category.

Wall Street play for which we pay

By John Kay

Published: August 3 2010 23:20 | Last updated: August 3 2010 23:20

King Sandy: a little known tragedy, comedy and history in five acts, by William Shakesdown. Based on ‘King of Capital: Sandy Weill and the Making of Citigroup’, a story by Amey Stone and Mike Brewster

Act I. Brooklyn. A dead tree stands to the right of a tumbledown brownstone house. The Brooklyn Bridge and the skyscrapers of Wall Street are in the background. Three witches greet the young boy standing on the front steps.

EDITOR’S CHOICE

More from this columnist – Aug-03

“All hail to thee, that shall be boss of Shearson,” says one.

“All hail to thee, that shall be leader of Travelers,” says another.

“All hail to thee, that shall be King of Wall Street, thereafter,” says the third.

Young Sandy, shaken, ponders the implications as the curtain falls.

Act II. Manhattan. Sandy, his belongings in a bundle on a stick, crosses the Brooklyn Bridge to seek his fortune. He starts as a shoe-shine boy but his talent is quickly recognised and he becomes chief counsellor to the land of Shearson. He forges an alliance with the duchy of Amex, ruled by the patrician John Robinson. But the Duke resents the clever, uncultured, grasping Sandy and sends him into exile. “There is a world elsewhere,” Sandy proclaims.

Act III. Baltimore. Sandy and his brilliant lieutenant, Jamie, plot their comeback. Building a band of faithful Travelers, Sandy and Jamie move step by step towards Wall Street, finally storming the bastions of Salomon and Smith Barney.

Act IV. Washington and Manhattan. The triumphant Sandy is in a tent outside Washington. The omnipotent King John, Lord of the Citi, enters. Sandy and John agree to unite their kingdoms. Back in Manhattan, Sandy exiles the now too powerful Jamie, assassinates King John, and is proclaimed King of Wall Street.

In the final scene, the fool Grubman is seen playing his fife all the way up Manhattan from Wall Street. Followed by an admiring crowd, he distributes parcels of fool’s gold and internet magic.

Act V. Manhattan and Washington. The fool is exposed: his parcels are empty. He is banished. King Sandy, his reputation tarnished, is deposed. Under the regency of the Chuck Prince, the Citi is riven by competing baronies. The land of Lehman is pillaged by its own citizens. Barons mob the Court, shouting: “Where are our bonuses?”

The situation is calmed by the arrival of Barack the Great, newly elected emperor. His counsellors, Bernanke and Geithner, are at the head of a long train bearing all the treasures of the Americas. The barons break open the chests and rush off with the treasure. Jamie, returned from exile in Chicago, is crowned new King of Wall Street.

***

At the medieval courts Shakespeare described, the exercise of power was not a means to an end, it was itself the end. Kings and barons sought principally to extend their territory. If they occasionally claimed that the purpose was to bring the benefits of their wise rule to a wider public, the assertion was little more than a smokescreen for personal ambition. The rulers aimed to be exalted as rulers of wider domains and to levy taxes on ever more peasants. The political and economic environment has been transformed. But human nature has not, and the factors that drive powerful men today are little different from those that drove them five centuries ago.

The fine robes of Shakespeare’s princely characters were paid for by the work of the peasantry, the men and women who tilled the fields and garnered the crops. Their labours yielded revenues to support lifestyles entirely disconnected from their own experience, people who knew nothing of agriculture and cared less, and whose activities were sometimes disruptive to day-to-day economic activity but mostly irrelevant. Once there were sowers and reapers, now there are bank clients and factory workers; once there were palaces and carriages, now there are McMansions and private jets. Much has changed, yet much remains the same.