Whenever a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies.

That, of course, is from Gore Vidal, 1925-2012.

Econ 271 students saw that in this Tyler Cowen article “The Inequality that Matters.”

Creative Instruction

Whenever a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies.

That, of course, is from Gore Vidal, 1925-2012.

Econ 271 students saw that in this Tyler Cowen article “The Inequality that Matters.”

Continuing our series of posts about what economists believe, my colleague reminds me of the list at the beginning of Deidre McCloskey’s text, The Applied Theory of Price, available free for download!

Here’s McCloskey in all her rhetorical glory:

Considering the obstacles, economists agree about a surprisingly large number of things. Their agreements, in fact, are often about things that noneconomists would think silly or wrong or even evil. That is, economists are in surprising agreement about surprising statements…

The list of surprising agreements is a long one. Most of the 20,000 or so members of the American Economic Association would answer yes to questions such as:

Although the text was written more than thirty years ago (!), the policy issues still seem rather germane — the burden of social security taxes, energy conservation, rising standards of living. I like the bit about the longshoreman.

McCloskey does not weigh in here on drug legalization, but my guess is that she would argue that economists would agree on certain aspects. First, decriminalization or legalization would definitely lead to more drug use, due to both supply and demand increases. Second, the level of violence associated with organized crime and others would decrease. What there appears to be no consensus on in whether the goods outweigh the bads, or if the distributive implications are desirable, or even whether we want to be a society that “endorses” drug use.

That, my friend, is the classic positive v. normative distinction.

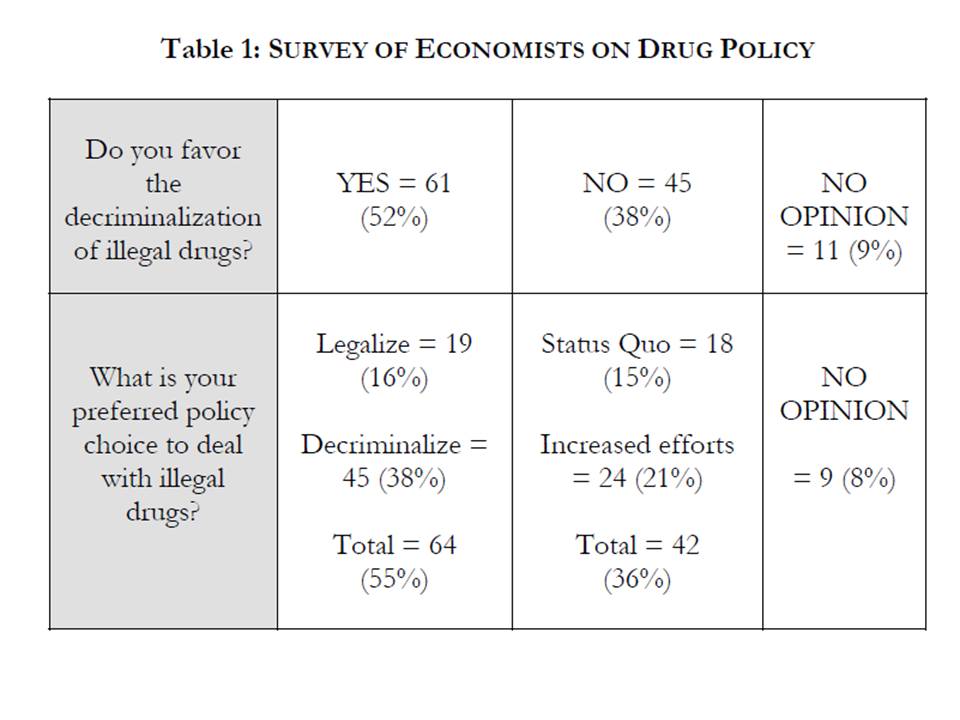

In our usually dormant comments section, Dr. T has questioned whether economists really overwhelmingly favor drug legalization, a claim made in a recent NPR segment. To address this concern, I consulted the Econ Journal Watchand its on-point article from Mark Thorton “Prohibition vs. Legalization: Do Economists Reach a Conclusion on Drug Policy?”

From the abstract:

A random survey of professional economists suggests that the majority supports reform of drug policy in the direction of decriminalization. A survey of professional economists who have published on the subject of drug prohibition and expressed a policy judgment indicates an even greater consensus which is critical of prohibition and supportive of policy reforms in the direction of decriminalization, and to a lesser extent, legalization.

Thorton concludes that there is in fact no consensus, and after taking a look at his summary statistics, I’d have to agree. That said, it does appear that there is solid support for some form of liberalization.

You can check the article to see some snippets from “vital” economists such as Robert Barro, Gary Becker, David Henderson, Jeffery Miron, and William Niskanen.

You can check the article to see some snippets from “vital” economists such as Robert Barro, Gary Becker, David Henderson, Jeffery Miron, and William Niskanen.

In the previous post, I mentioned the Robert Whaples survey of American Economic Association (AEA) members on their public policy views. Of course, Whaples isn’t the only one with access to Survey Monkey, and with the help of some of my colleagues, we gave the same survey to students in Freshman Studies, Economics 100, and Economics 300 courses.

The Freshman Studies sample (n=26) should be fairly representative of incoming freshman population, as every student takes freshman studies and these students are allegedly distributed randomly across the sections. I have data from two sections with a 90% response rate. The Econ 100 course is predominantly freshman as well, but is a much different cross section of the University, with 70% planning to major in economics or some other social science. The Econ 300 is, of course, generally for students taking the first “major” step to joining Team Econ down here on Briggs 2nd. It is well-worth noting that the Econ 100 (n=35) and Econ 300 students were surveyed at the beginning of the course,* not the end. Perhaps next year we will switch that up.

The survey participants rate the questions on a 1-5 scale, with 1 being strongly disagree and 5 being strongly agree.

Here are selected results, sorted by the scores of AEA members:

Continue reading Lawrence Students v. Card-Carrying Economists

You have probably heard about the exasperated President Truman asking for a “one-handed economist” because all of his economics advisers were prone to saying “on the one hand… on the other hand.” Or, perhaps you’ve heard of the First Law of Economists: for every economist, there exists an equal and opposite economist (with the Second Law of Economists being that they are both wrong). Or, you might have even heard that if you were to lay all economists end-to-end, they still wouldn’t reach a conclusion.

Hilarious, indeed, and fair enough, it’s true that our profession is prone to qualifying our assessments. But as a recent NPR Marketplace segment uncover, there are some thing views that seem to hold from east-to-west, from north-to-south, and, yes, from left-to-right across the profession.

And here they are, six shared policy beliefs among economists:

One: Eliminate the mortgage tax deduction, which lets homeowners deduct the interest they pay on their mortgages. Gone. After all, big houses get bigger tax breaks, driving up prices for everyone. Why distort the housing market and subsidize people buying expensive houses?

Two: End the tax deduction companies get for providing health-care to employees. Neither employees nor employers pay taxes on workplace health insurance benefits. That encourages fancier insurance coverage, driving up usage and, therefore, health costs overall. Eliminating the deduction will drive up costs for people with workplace healthcare, but makes the health-care market fairer.

Three: Eliminate the corporate income tax. Completely. If companies reinvest the money into their businesses, that’s good. Don’t tax companies in an effort to tax rich people.

Four: Eliminate all income and payroll taxes. All of them. For everyone. Taxes discourage whatever you’re taxing, but we like income, so why tax it? Payroll taxes discourage creating jobs. Not such a good idea. Instead, impose a consumption tax, designed to be progressive to protect lower-income households.

Five: Tax carbon emissions. Yes, that means higher gasoline prices. It’s a kind of consumption tax, and can be structured to make sure it doesn’t disproportionately harm lower-income Americans. More, it’s taxing something that’s bad, which gives people an incentive to stop polluting.

Six: Legalize marijuana. Stop spending so much trying to put pot users and dealers in jail — it costs a lot of money to catch them, prosecute them, and then put them up in jail. Criminalizing drugs also drives drug prices up, making gang leaders rich.

The catch, of course, is that politicians tend to not like these policies. You can listen to the full NPR segment here.

For more on what economists do and don’t agree on, you might check out this survey from Robert Whaples at the Econ Journal Watch.

Here is Stanford’s Jon Krosnick giving a very nice talk about the U.S. public’s view on climate change. Krosnick responds to the idea that “Climate-gate” and media saturation and the economic malaise have somehow changed public opinion, and convincingly argues that they have not. Indeed, Krosnick shows that the public generally trusts scientists, believes in global climate change, believes in human activities’ impact on the changing climate, and generally believes the scientific community knows its science.

Take a look starting at 23:30, though. It turns out that when scientists start talking about policy, all you-know-what breaks loose. The public basically doesn’t believe that scientists know what they are talking about when they start talking about policy. It gets worse, though — when scientists talk policy, respondents are less confident that the scientists know their science! The final kicker is that it dampens support for government action on climate change.

Check it out for a marvelous cautionary tale.

I wonder if this carries over to economics and economic policy?

Politicians pontificate profusely about their prodigious plans for procuring Federal budget sanity. For the most part, their potential policy projectiles miss the mark. In an essay in today’s Wall Street Journal entitled “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Budget** But Were Afraid to Ask,” David Wessel highlights six key facts that will constrain the efforts of these pugilistic pundits.

1. “Nearly two-thirds of annual federal spending goes out the door without any vote by Congress.”

2. “The U.S. defense budget is greater than the combined defense budgets of the next 17 largest spenders.”

3. “About $1 of every $4 the federal government spends goes to health care today. That is rising inexorably.”

4. “Firing every federal government employee wouldn’t save enough to cut the deficit in half.”

5. “The share of income most American families pay in federal taxes has been falling for more than 30 years.”

6. “The federal government borrowed 36 cents of every dollar it spent last year, but had no trouble raising the money.”

These “facts” form the basis for Wessel’s new book to be published next week and should inform political debate. I won’t hold my breath regarding the latter point. The cartoon reflects an earlier time period, but the political dynamics today, as characterized in the cartoon, still obtain.

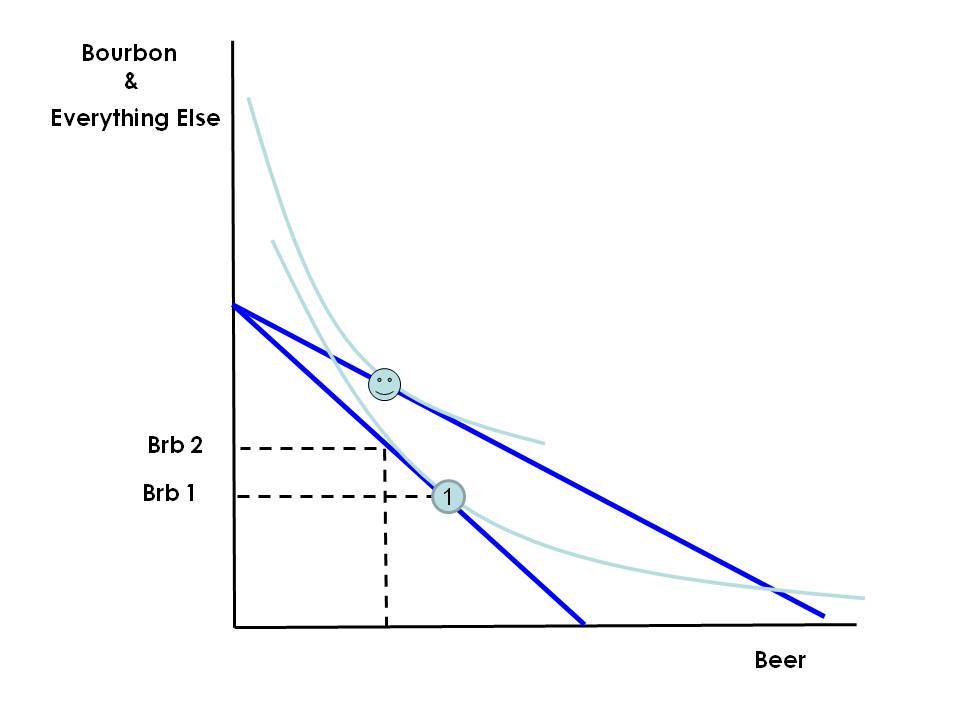

Professor Gerard has treated us again to some good, clean microeconomic fun. I think he is correct, and the bottom line is: if beer is a Giffen good, its consumption can fall as its price rises. His elaboration (and correction) of Yglesias is very nice, as is his translation of Yglesias’s argument into the neat graphical device of the iso-alcohol constraint. Yglesias’s original statement, however, that “…another possibility is that people hold total spending and total alcohol consumption [constant]…” strikes me as pretty sloppy, by Briggs 2nd floor standards. Why would one keep alcohol consumption constant, in the face of a price change? Changing circumstances leading to no change in a choice variable (alcohol consumption) is always suspicious, especially in a continuous model like this.

Yglesias seems to be groping (in the dark) for a characteristics model—in other words, a model where people care about characteristics (alcohol and taste) of goods, not the goods directly. This sort of model was thoroughly worked out in the 1970s, mainly by one famous Kelvin Lancaster. In this example, there are two goods, beer and bourbon, and they both have two characteristics (to various degrees), viz. alcohol and taste. The utility function is defined on alcohol and taste, and the quantities of characteristics consumed depend linearly on the quantities of beer and bourbon purchased. So, I thought, perhaps there is something interesting going on here. Maybe, just maybe, we could have a Giffen good even if the utility function (on characteristics) is perfectly normal, i.e., not Giffen. Luckily, before I got too absorbed in linear transformations, I took Google Scholar for a spin, and soon got to “A Contribution to the New Theory of Demand: A Rehabilitation of the Giffen Good” by Richard G. Lipsey and Gideon Rosenbluth, published in The Canadian Journal of Economics in 1971. Here is a taste from the Introduction:

Three of the most commonly used illustrations of possible Giffen effects are: Bread and meat, beer and whiskey, and Marshall’s account of transportation. There is a common feature of these three examples which “common sense” suggests is an essential requirement for a Giffen good and indeed for an inferior good, of which the Giffen good is a special case: there must be a “superior” good which shares one or more of the characteristics of the inferior good. If, for example, meat is substituted for bread as income rises, this implies that there is a want-satisfying characteristic shared by the two goods, in respect of which the substitution takes place. Bread must be a cheaper source of supply of this characteristic than meat, else the substitution would not depend on a rise in income. The reader can satisfy himself that similar reasoning applies to the other two examples.

They then go on to explain very neatly how Giffen goods could easily arise even if we assume that the utility function (on characteristics) excludes the possibility of a Giffen characteristic. Basically, if the income elasticity for characteristic 1 is very high compared to the income elasticity for characteristic 2, then an increase in real income will push the consumer to want so much more of characteristic 1, that just consuming more of the good that is more characteristic 1 intensive won’t do—he will have to cut back consumption of the other good to consumer even more of the good that is more characteristic 1 intensive. In our example, the income elasticity for taste is so much higher, that an increase in real income will push the consumer to want so much more taste that just buying more bourbon won’t do—he’ll have to cut back on beer and buy even more bourbon. However, as he does so, total alcohol consumption will still increase! (Remember, we assumed that there are no Giffen characteristics.)

I must say that I am pretty satisfied with the Lipsey–Rosenbluth explanation of why beer might be a Giffen good in this case. If the name Lipsey sounds familiar, that’s probably because of his association with The Theory of the Second Best, which probably requires a post of its own. (See also here.) And I would be remiss if I did not mention that Lipsey was a recipient of the 2006 Schumpeter award for the book Economic Transformations (co-written with two of his students).

I hereby propose that Griff’s Grill be renamed “Griffin Good” for a week in honor of economic science.

The clever graphic is one of Art Carden’s economic “memes” that has been circulating around in cybersphere for a day or two. The lesson, of course, is the law of demand — price goes up, people buy less; price goes down, people buy more.

But Slate’s Matthew Yglesias steps up and says that maybe it isn’t so!

Imagine a world with two goods—beer and bourbon—such that beer is cheaper per unit of alcohol than bourbon, but bourbon is tastier. Drinkers arrive at some kind of beer/bourbon mix based on their desires to (a) get drunk, (b) drink something tasty, and (c) have money left over for other activities. Now the price of beer falls…

The first thing to notice is that this is not a two-good world, as assumption (c) places us squarely in a three-good world: beer, bourbon, and other activities. More on that in a minute. Yglesias runs through a couple possibilities where people indeed drink more beer when the price decreases, as one would expect, but then he finishes with this zinger:

Yet another possibility is that people hold total spending and total alcohol consumption (constant) and use the budgetary headroom opened up by cheaper beer to buy less beer and extra bourbon.

So, let’s break this down. First off, total spending here is simply another way of saying the consumer has an income constraint. Second, the “budgetary headroom opened up” is the income effect from the price of a good in the consumption set decreasing. In other words, when the price of a good in a consumer’s consumption set falls, he effectively becomes richer because he can continue to buy his current consumption set, but now he has money left over to buy more beer, more bourbon, or more other activities.

If we go ahead and assume that our consumer has convex preferences, our standard assumption, then we know that holding utility constant that when the price of beer falls, the substitution effect will indeed induce more beer consumption.

But what about the income effect from the budgetary headroom? It’s possible that greater income leads to lower consumption of some goods (Ramen Noodles, bus rides, World Series viewings), and we call such goods inferior goods. Anyone who has taken price theory knows that I don’t need three goods to get people to buy more bourbon and less beer — I simply need beer to be an inferior good that is subject to a really big income effect. That is, the price of beer falls, the substitution effect leads our consumer to buy more beer, but the income effect from greater budgetary headroom overwhelms the substitution effect. Beer is a Giffen good and we call it a day.

Of course, economists have been looking for Giffen goods for a very long time, and there isn’t a long list, so maybe that isn’t the best route to go.

Instead of this, Yglesias provides this additional “iso-alcohol” constraint, where consumers want to keep overall alcohol consumption constant. If the standard two-good model, if you hand someone $1000, the beneficiary buys more beer and less bourbon (if bourbon is inferior), more bourbon and less beer (if beer is inferior), or more of both (if both are normal). With the iso-alcohol constraint, however, the third case is off the table and additional money will go to some other activity. Hence, for Yglesias’ case of less beer with more “budgetary headroom” to hold, we know that we would have to be in the second case with beer being an inferior good. At the same time, though, if I hand someone $1000, it’s possible that they buy more bourbon and less beer, which is Yglesias’ point to begin with: “use the budgetary headroom opened up by cheaper beer to buy less beer and extra bourbon.”

So, let’s collapse this back down to a world where we have two goods: (1) beer and (2) bourbon and everything else, where the consumer is subject to both the income and the iso-alcohol constraint (linear combinations of beer and bourbon that lead to an equivalent level of insobriety). For visual simplicity, assume that initial income constraint is the same as the initial iso-alcohol constraint. That is, the relative price of beer and bourbon is the same as the relative weights needed to achieve some level of insobriety. Also for simplicity, assume that the consumer initially spends all his income on beer and bourbon. The optimal consumption set denoted by the circle with the 1 with bourbon consumption of Brb 1, where Brb 1 constitutes all spending on goods other than beer.

Now along comes the decrease in the price of beer and all of a sudden we have a new budget constraint, one that pivots outward with the same Y intercept but a new X intercept. The potential consumption set has expanded. Clearly, the consumer can buy more than he bought before, and a new optimum consistent with less beer consumption is illustrated by the smiley.

Because the consumer wants to maintain the same level of alcohol consumption, the amount spent on bourbon has to be on the original budget constraint — in this case the distance Brb 2 represents the amount spent on bourbon and the amount necessary to maintain that level of alcohol consumption. The distance between Brb 2 and the smiley is the amount spent on other stuff. As you can see, Yglesias’ possibility collapses to the observation that “beer could be a Giffin good.” In other words, not likely at all.

It’s probably worth noting that the iso-alcohol constraint is problematic in its own right, as it implies a minimum level of consumption that might not be viable in a world where the price of beer and bourbon go up, or income decreases. In our example if the consumer is initially exhausting his income on beer and bourbon, any price increase or income decrease has the unhappy result that the iso-alcohol constraint cannot be satisfied.

Thank you to loyal reader Mr. P for the tip.

That’s hedge fund manager Hugh Hendry talking to Nobel-prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, as quoted in this Financial Times article.

See the exchange here. It gets interesting around 7 minutes for sure where Hendry suggests Greece will have to default or give creditors a “haircut” as it recognizes that it has unsustainable levels of debt.

But, back the FT piece, Hendry thinks we are on the verge of financial anarchy, that France will nationalize its banks, that China is hosed, that Japan is in trouble, and that the global debt situation is so dire that “the scale and the magnitude of the problem is greater than their (read: governments’) ability to respond.” He concludes that we are within ten years of an epic financial collapse reminiscent of the 1930s.

The good news?

The US isn’t as bad off as Brazil, India, Russia, and China. And that the financial collapse will create investment opportunities of a lifetime.

Have a good weekend.

My mentor and now colleague Mark Montgomery of Grinnell College has penned an essay on the social conventions of professors walking around with buds plugged in their ears.

It’s a cliché that people like me, whose computational experience began with punch cards, can feel overwhelmed by the explosion of electronic gadgets. But I find that the difficulties are less technical than emotional and social. Consider, again, my relationship to my beloved iPod. Is it OK for me to “wear” it around campus? Or does it undermine 165 years of institutional dignity for a gray-haired full professor to be seen strolling through the quads with two wires dangling from his head?

The article is in the Chronicle of Higher Education and, judging by the comments, is highly hilarious to our brethren. What I respect about it most, though, is that he manages to fit in a brief lesson on the economics of signalling near the end:

Ironically, I find that among the earphone-wearing public (that is, most people under 23), the iPod can actually enhance communication. With students I can use it to set the tone of a conversation before a single word has been uttered. Some examples: (1) One earphone removed and held poised an inch from my ear means I’m about to say: “If you want to discuss your exam grade, come to office hours.” (2) Both earphones removed, allowed to dangle: “Where is the assignment that was due on Monday?” (3) Earphones removed, wires wrapped around the iPod, device tucked in jacket pocket: “Why have I not seen you in class all week?”

Indeed.

For more from the good professor, see the essays at his website.

Professor Montgomery is tentatively slated to speak in our Economics Colloquium this coming year, so we look forward to that, too. You can check out his research interests and publications here.

Is your internet service shoddy? Do you find that your connection is in and out? Do you think major data centers have the same types of problems?

The answer to that last question appears to be yes.

In a wonderfully titled article, “Guns, Squirrels, and Steel: The Many Ways to Kill a Data Center,” Wired provides a nice rundown of the principal culprits (allusion here).

As the title indicates, squirrels can account for up to 15-20% of cable damage at some data centers. The other culprits include hunters shooting out insulators, lightning strikes, explosions, and thieves — like thieves thieves, not virtual ones.

For those of you unfamiliar with the scourge of squirrels, let me just say that there are significant resources dedicated to fending off these furry little guys, and there is no one right way to do it (see, for example, the classic Outwitting Squirrels: 101 Cunning Stratagems to Reduce Dramatically the Egregious Misappropriation of Seed from Your Birdfeeder by Squirrels).

101 ways. And that’s just for bird feeders, not Amazon.com!

And the Outwitting Squirrels guide probably doesn’t include this or this, though honestly I haven’t consulted it lately.

The LIBOR scandal is all over the financial press, and as the headline here indicates, it might be a big deal. Typically, when you see a quotation like that, it is from a blogger residing in his parents’ basement. In this case, however, the source of the quote happens to be MIT distinguished professor Andrew Lo.

And he’s not alone.

Former New York governor Eliot Spitzer seems to concur, saying that “LIBOR is huge. This is about as big as it gets in the financial world.”

So, what is this all about?

Essentially, it appears that a group of traders colluded to set the LIBOR rate, an interest rate that is at the center of international financial markets, over the course of several years. Indeed, roughly $800 trillion in financial instruments are tied to LIBOR. A second issued now gaining traction is that it is possible that U.S. regulators knew about this years ago.

Both cases seem to undermine the integrity of financial markets generally, and that is simply not a good thing in terms of linking up savings and investment.

Here is a helpful infographic from AccoutningDegree.net. Not to be outdone, here is another helpful infographic via the New York Times.

You will probably be reading about this one for some time. I liked this piece in The Economist, which takes a forward look at these “Banksters.” I also really liked this piece from Ed Dolan on why LIBOR rates were subject to manipulation — motive, means, and opportunity.

Columbo couldn’t have said it better himself.

Today is a summer visit day for prospective students, so hello to all of you good folks from Briggs 2nd.

In Monday’s Financial Times, economics editor Martin Wolf explains why the “end” will not be soon. He notes that it has been almost five years since the beginning of our contemporary financial turmoil, if one marks such by the first major sign of sub-prime mortgage problems in the U.S. He characterizes the past five years as ones if which policies (both monetary and fiscal) have been very aggressive; yet economies – US, Europe and Japan – have been stagnant. David Levy describes such a situation as a “contained depression”; that is, these economies feature excessive leverage (debt), especially in household and financial sectors and expansionary macroeconomic policy. Stated differently, the private sector continues to de-leverage (reduce its debt level) while governments attempt to counter such counter-cyclical demand with public borrowing and money creation. The two have, in fact, been connected, as central banks purchase much of the newly created governmental debt. In short – remember the world of IS-LM – there is no crowding out. The charts below show the depth of the problem.

The lower right hand graph shows that private sector debt in the US has come off its peak (of 296% of GDP in 2008) by roughly 17% (250% of GDP) about where the economy was in 2003. If Reinhardt and Rogoff are correct, we have at least two more years to go, given that an “average” balance sheet recession last seven years. If the mid-1990s feature a stable debt to GDP ratio, of just under 200% of GDP, we are only half-way “home.” In terms of economic growth, clearly, the Eurozone has yet to recover; while, the US and Germany have just barely exceeded their previous GDP peak (in 2007) – see upper left graph.

According to Wolf,

We know that big financial crises cast long shadows, particularly in countries whose underlying rate of growth is modest, which makes de-leveraging slow. Policy must both sustain demand and facilitate de-leveraging. This means aggressive monetary and fiscal policies, working in combination, along with interventions aimed at recapitalising banks and accelerating restructuring of private debt.

Policies designed to bring down public debt prior to the end of private de-leveraging will dampen economic growth and extend the period of adjustment. Though public fiscal consolidation is necessary for long run stability, if it is not crafted to be consistent with an economic growth path that can meet the required debt service, economic stagnation or worse will be the order of the day.

Wolf concludes that

Far too much policy making and advice neither recognises the post-crisis challenges nor crafts effective answers. The heart of the matter is accelerating de-leveraging, while promoting recovery. By that standard, the policies now in place are, alas, very far from good enough.

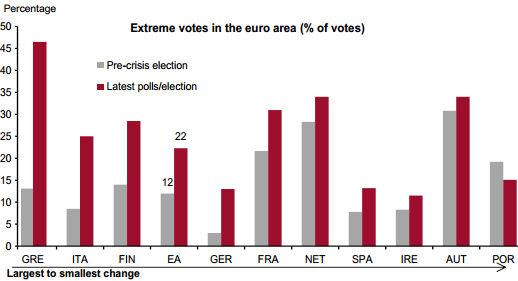

Marginal Revolution points us to some disturbing evidence on the increasing polarization of the European electorate.

The source is Credit Suise, so you can track that down to see what “extreme votes” means.

Here’s some more on the situation in Greece. When I see a blog post titled “The Scariest Chart in Europe Just Got Even Scarier,” I typically think the author is invoking some grand hyperbole.

Perhaps not in this case.

Here’s Derek Thompson at The Atlantic:

Thompson points us to a link that draws this conclusion: “Spain is doomed and Greece is toast.” Of course, last year we pointed to Michael Lewis’s similarly dire predictions for Greece, where he observes “the closer you look, the worse it gets.” He concluded Greece is simply incapable of reform in its current form.

That unemployment bar looks like a big fuse.

I am just returning from the 12th Conference of the Society for the Advancement of Economic Theory at the University of Queensland, which was very successful in that a great many economic theorists from all over the world got together and presented their work. I presented my recent work on falsifiability, complexity, and revealed preference in a session devoted to revealed preference theory.

One of the sessions was a panel discussion on the question “What Can Theory Tell Us About the Financial Crisis?” (My comments below may reflect my (mis)interpretations.) The moderator, Rohan Pitchford (Australian National University) foreshadowed some of the comments to come by stating at the outset that the panelists should feel free to turn that question around, asking what the financial crisis can tell us about economic theory. Some of the comments made were expected—for example, that theory has, of course had everything about the crisis figured out, just take a look at (Name, Year), and (Name, Year), and (Name, Year)… you get the picture. Even granting that (Name, Year) were all brilliant, this is hardly answering the question in a satisfactory way. Another point, often said, but not without reason, is that one should not expect economic theorists to be able to predict when a crisis would take place, and predicting that there would be one (some time) is hardly news. In fact, if the crisis could be predicted correctly, it is often repeated, it wouldn’t take place! And if it did, (some) economic theorists would be very rich.

But some of the panelists made some interesting points. Continue reading Dispatch from Down Under

Continuing our string of posts about the EU, here is a remarkable but perhaps unsurprising fact: Since gaining its independence in 1829, Greece has defaulted on or rescheduled its external debt five times (1826, 1843, 1860, 1893, and 1932). Greece has been in default roughly half the time period since 1829.

That is culled from the astonishing This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly from Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff.

I’m finally plowing through some of summer reading recommendations. This particular recommendation was from 2010.

Our recent guest, Brad Bateman from Denison University, has an oped in the Pittsburgh Post Gazette reflecting on a recent conference in Greece, discussing the future of the liberal arts college.

The piece, like much of the news out of Europe these days, will both shock and annoy.

Here’s a taste:

As it is, the government will not itself accredit private colleges or universities, and a law passed in the last decade disqualifies anyone with a degree from a private university from being a college professor. Therefore, for instance, a faculty member at the American College who earned a an undergraduate degree there and then went on to Princeton, Harvard or Oxford for graduate work is not legally able to teach. One of the best colleges in the country has been placed under constant duress in this way.

Why would anyone try to close a highly successful college? Why would anyone want to take educational opportunities away from young people in a struggling economy?

Because Greek public universities and their professors act like a cartel. Making private universities essentially illegal and preventing their graduates from teaching increases enrollment at state universities and benefits the professors who work for them. Both of the main parties buy votes by protecting these professors’ jobs.

Sadly, the future doesn’t appear to be too bright for Greece. Unless you count watching the economy burn.