Here’s the update from the reading group.

On the subject of big, fat profits in the financial sector, you might consider visiting some of these pieces. On the subject of big, fat incomes in the financial world, Cowen offers up a simple theory on why so many smart young people go into finance, law, and consulting. Adding fuel to this fire, “Mr. D” sends me this helpful blog post from Ezra Klein, arguing that Ivy Leaguers head to the Street because that’s where they get their “real” education. Do you buy that? And, in a similar vein, “Mr. P” wants to know why Americans don’t elect scientists.

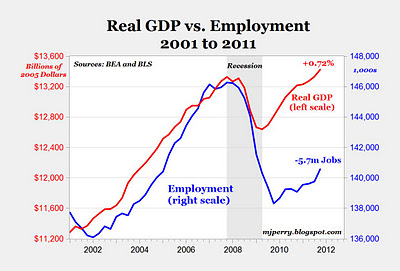

We left off yesterday with the open question of what the best-case scenario is for market economies moving forward. Where are the big productivity gains going to come from? What type of work is to be done? Is manufacturing dead or alive, or does it even matter? (See Professor Finkler’s previous post). Has John Stuart Mill’s concern about the inevitable decline in radical breakthrough inventions finally come home to roost?

And, this opens the door for next week’s book, Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s Race Against The Machine: How the Digital Revolution is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy. There are a couple of secondary sources on this, as well, including pieces from The Economist and The Wall Street Journal.

By all rights, this term’s 391 DS reading group should be titled Keynes, Cowen, Brynjolfsson, Backhouse, Bateman, McAfee, and Capitalism, but that doesn’t quite roll of the tongue, does it?

Nor would it fit on your transcript.

The Economics Department

The Economics Department