In the past, I’ve often harangued my environmental economics students with the question of why, if we are running out of natural resources, the futures markets don’t project substantial increases in oil prices. After all, a constrained supply should lead to higher prices on the one hand, and the industrialization of China, India, and other countries suggests that world demand will continue to increase (or, at least, it won’t decline substantially). Add together lower supply and higher demand and we should be seeing higher prices.

The scholars at www.Env-Econ.net have a nice overview of the canonical Hotelling Rule that provides some logic for increasing oil prices, along with a potential price trajectory based on marginal production costs.

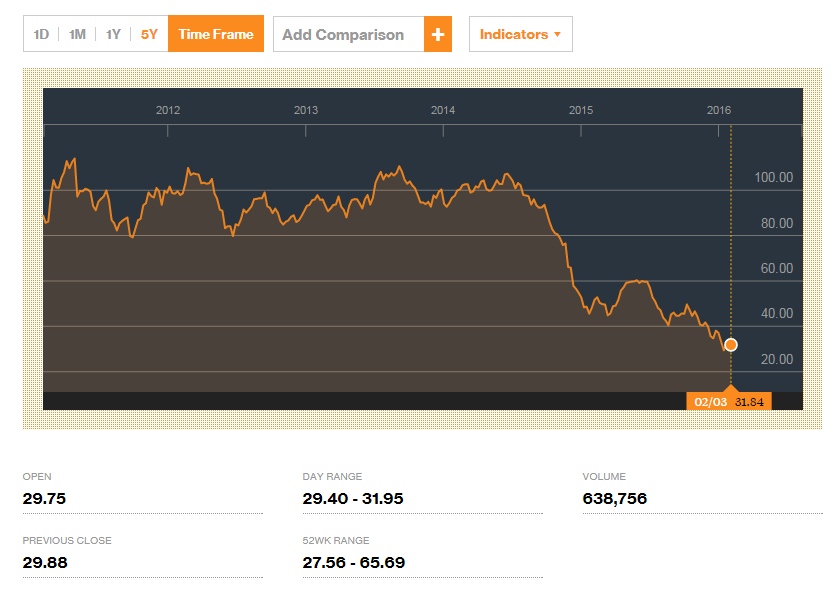

Yet, anyone looking out in the world today certainly has noticed that oil prices have dropped precipitously. This screen grab from Bloomberg shows that in late 2014 oil prices moved from the $80-100 range to the $40-$60 range for the better part of 2015. Prices have continued to slide, and were just north of $30 as of a few minutes ago.

So what are we to make of all of this? I typically use commodities markets to motivate supply and demand, and have trouble convincing students that Big Oil doesn’t rig the world price (I wonder where students get *that* idea?). Even with recent declines, students still have trouble reconciling their views of recourse scarcity and commodity prices (as do I).

James Surowiecki has a nice write up (as usual) in the New Yorker about the strong positive relationship between oil prices and stock prices, and tells us a story about how cheaper oil might not be the best thing for the US economy. Binyamin Applebaum covers some of the same ground in the New York Times (“This time, cheaper oil does little for US economy”), as do Javier Blas and Simon Kennedy at Bloomberg (“For Once, Low Oil Prices May Be a Problem for World’s Economy”).

Taking a step back, the brand new Journal of Economic Perspectives gives us a symposium on oil and gas markets that takes a look at availability and use, price volatility, and the links between natural resource development and economic development. As ever, the JEP is a good starting point to begin a deep dive into what economists have been thinking about on the topic.