I probably have more thoughts on this than I will convey here, but I have seen a number of unusual items related to the economics of climate change. First, a few weeks ago I saw that University of Sussex economist Richard Tol had begged off the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change because he disagreed with how the recent IPCC technical report was translated into “journalist speak” in the Summary for Policy Makers (SPM). The SPM takes several thousand pages of technical reports and boils them down to an Executive Summary in the 25-50 page range.

From The Guardian we have this: “Richard Tol told Reuters he disagreed with some findings of the summary to be issued in Japan on 31 March,” and the story follows up with some choice quotes from Professor Tol:

The drafts became too alarmist…. It is pretty damn obvious that there are positive impacts of climate change, even though we are not always allowed to talk about them…. They will adapt. Farmers are not stupid.

Okay, here is a rebuttal from an IPCC co-author.

Of the 19 studies he surveyed only one shows net positive benefits from warming. And it’s the one he wrote,” said Bob Ward, policy and communications director of the Grantham Research Unit on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics.

More on Tol later.

Meanwhile, Harvard’s Robert Stavins — a giant in environmental economics, really — has come out and publicly harangued the IPCC over its SPM saying “the resulting document should probably be called the Summary by Policymakers, rather than the Summary for Policymakers” (his emphasis). Professor Stavins is specifically addressing the part of the report that he helped coordinate, and is very clear that it is the SPM, not the chapter it is based on, that he takes issue with.

As someone in teaching environmental economics year in, year out, I can say I am a more than a little distressed that some top-flight economists are worrying about the politicization of the IPCC SPM.

Now back to Professor Tol, who is author of a very influential piece in the 2009 Journal of Economic Perspectives, “The Economic Effects of Climate Change,” that evidently contained some errors. Here’s Tol in “”Correction and Update: The Economic Effects of Climate Change” from the most recent JEP:

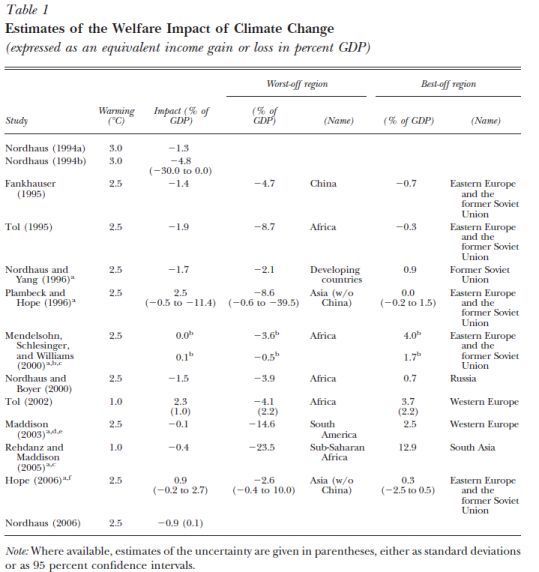

Gremlins intervened in the preparation of my paper “The Economic Effects of Climate Change” published in the Spring 2009 issue of this journal. In Table 1 of that paper, titled “Estimates of the Welfare Impact of Climate Change,” minus signs were dropped from the two impact estimates…

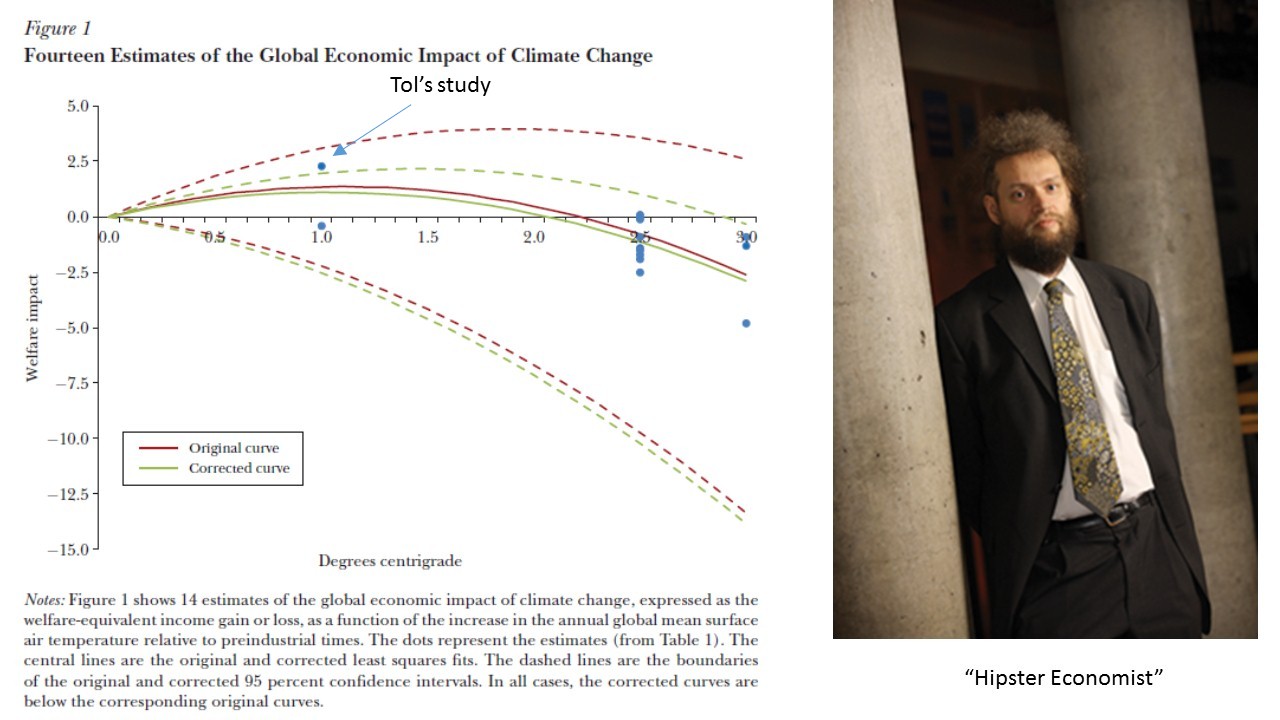

Gremlins, wow. I guess that’s putting a good face on publishing erroneous data in the profession’s flagship journal. Here’s the updated figure:

The Figure is from the JEP article (click for a bigger image); the “hipster economist” reference is here.

The kerfuffle over the figure is that the little dots represent the central estimates, and most of the estimates show negative impacts on GDP. The glaring exception is Tol’s own estimate of a 2.3% increase at 1 degree (C) of warming, which likely accounts for the shape of the fitted curve (the other study he reports with 1C warming estimates a loss of -0.4% of GDP). As the quote critical of Tol says that “of the 19 studies he surveyed only one shows net positive benefits from warming. And it’s the one he wrote.” That appears to be approximately accurate, though there is one other study that estimates zero to 0.1% increase at 2.5 degrees warming.

The larger issue is probably that the economic impacts simply aren’t as big as one would think. Of the 20 studies Tol cites, about half look at 2.5C of warming, and the average impact on world GDP among these studies is about a 1% of world GDP.

Unfortunately, most studies haven’t gone out very far past that, and I would guess that most people who have looked at carbon emissions and projected temperature increases believe the impacts will exceed 2.5C, and no matter who you ask, damages appear to be increasing at an increasing rate at that point.

The link to the article is above, and all the data from the article are available here. Tol has a more complete essay on his views in the Financial Times.

In this, the 500th post on the Lawrence Economics Blog, we bring you a

In this, the 500th post on the Lawrence Economics Blog, we bring you a

Almost unnoticed, this week marks a terrible week for advocates of market solutions to environmental problems, including various cap-and-trade systems. The Wall Street Journal

Almost unnoticed, this week marks a terrible week for advocates of market solutions to environmental problems, including various cap-and-trade systems. The Wall Street Journal  BP’s stock, which traded at a 52-week high of $62.38 on Jan. 19, 2010, closed on June 1 at $36.52 a share, down 15% on the day. The post-spill sell-off has wiped out some $68 billion of BP’s market value, knocking it down to $114 billion. With the stock now in the cellar, some speculation even has it that BP may attract a buyer.

BP’s stock, which traded at a 52-week high of $62.38 on Jan. 19, 2010, closed on June 1 at $36.52 a share, down 15% on the day. The post-spill sell-off has wiped out some $68 billion of BP’s market value, knocking it down to $114 billion. With the stock now in the cellar, some speculation even has it that BP may attract a buyer. He finds big impacts. The red line in the picture is his estimate of the time series of BP’s stock price without the spill, and the black line is the actual price. Seems like a big effect.

He finds big impacts. The red line in the picture is his estimate of the time series of BP’s stock price without the spill, and the black line is the actual price. Seems like a big effect.