Those of you who are acquainted with my writing on this blog probably know that (a) I study mortality risks, and (b) I sometimes comment on how these risks change when the clocks spring forward and fall backward. This fall is no exception, as I have a piece in the venerable Costco Connection* making the case that maybe keeping Daylight Saving Time as is wouldn’t be the worst thing to happen to the world. (I could have made the case the other way, as the policy decision here is very unclear, which tends to favor the status quo).

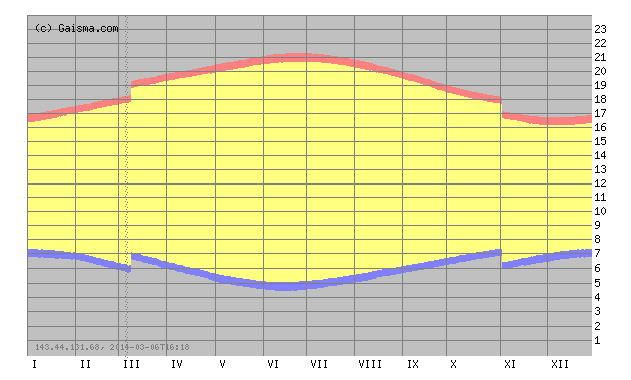

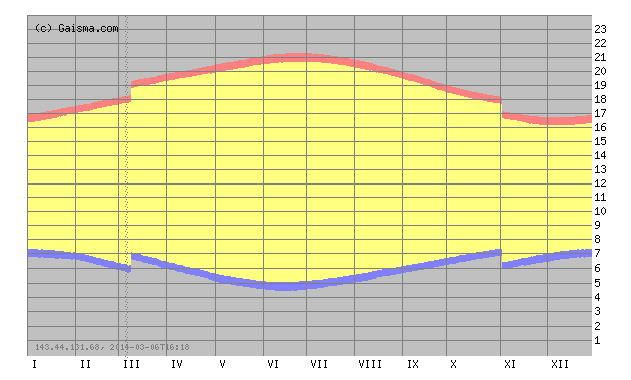

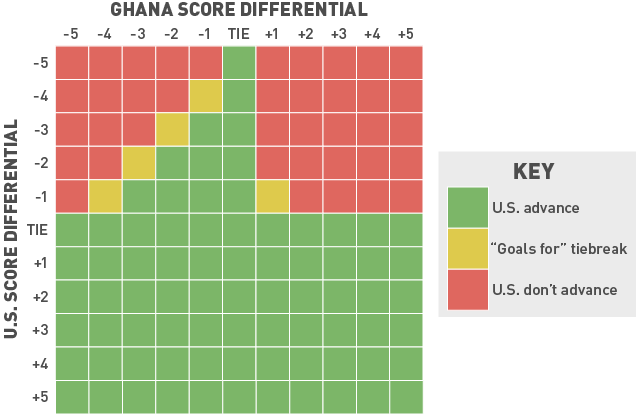

As per usual, the the remarkable Gaisma.com site shows us what’s at stake here in Appleton. The break in the series starting in month 11 is upon us:

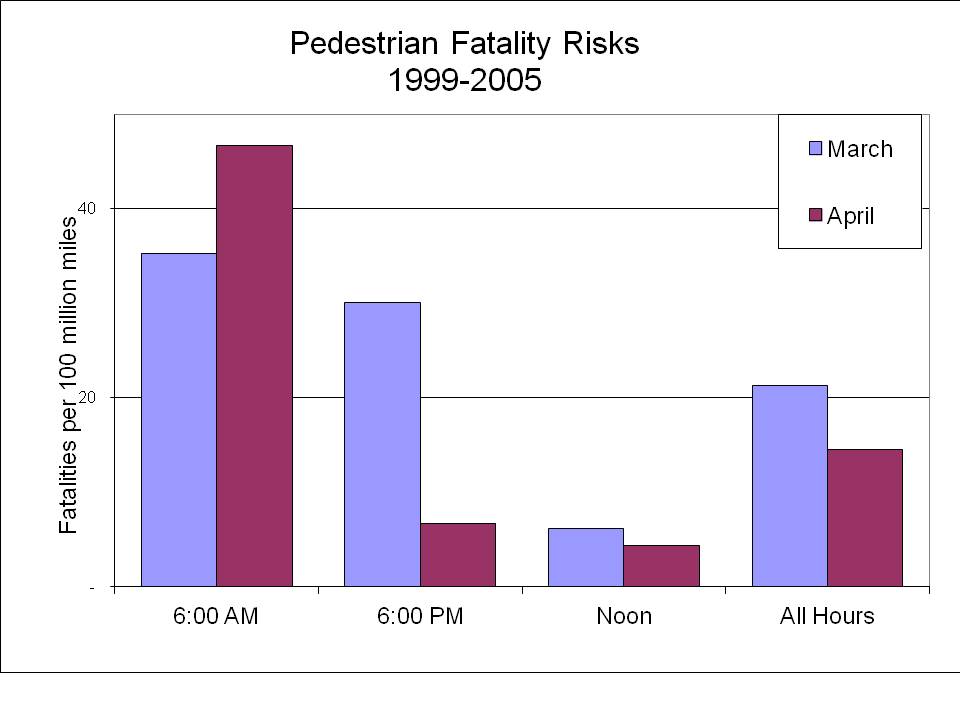

What does this mean for you? Well, starting Sunday it is going to be dark at 5 p.m. meaning that you are far more likely to get hit by a car at 5 p.m. next week than you are this week. When I say “far more likely,” our estimate is that the risk is about three times as high!

Of course, you are also far less likely to get hit at 6 a.m. in the extremely unlikely event that you are out 6 a.m. But, notice, January 1 the sun won’t rise until after 7 a.m., and if DST was permanent, that would be 8 a.m. Sunlight is the ultimate scarce resource.

Here is our previous coverage.

* The picture in the Costco piece is of me enjoying some daylight at Wrigley Field. Should Daylight Saving Time be eliminated? Of course not! More daylight means more daytime ball games.