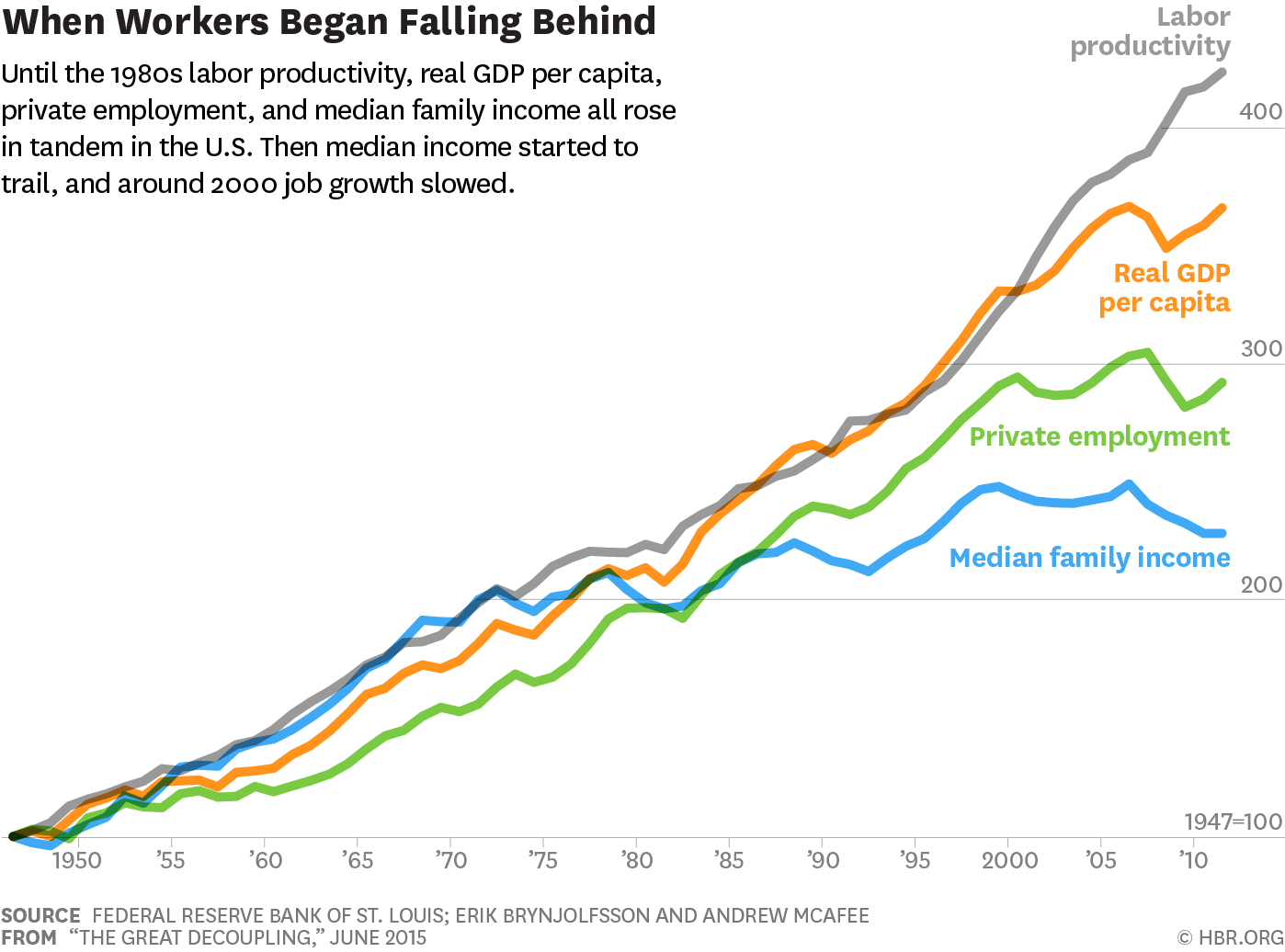

In previous blog postings (here and here), I have addressed some of the key myths regarding international trade as well as the difficulties in determining whether U.S. exchange rates are over, under, or fairly valued. This posting addresses how the forces that drive globalization have changed and so has the distribution of income (in both global and advanced country terms.) Richard Baldwin’s new book The Great Convergence suggests that a major change in the forces of globalization took place around 1990. He divides economic history into three broad periods: pre-globalization (until 1820), globalization I (1820 to 1990), and globalization II (from 1990 to the present.)

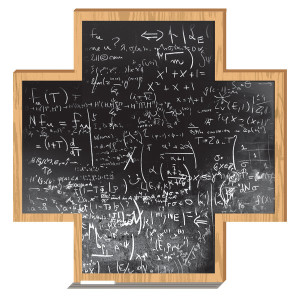

The graphic above (from a recent Baldwin’s presentation) displays the three primary forces that affect the magnitude and character of globalization. For further analysis including Milanovic’s “elephant” chart on the global distribution of income, see the full posting here.

.