Estimates of GDP growth vary widely (often well over 1 percentage point) from the initial one (typically at the end of the first month after the quarter) to a final one (up to a year later). This post addresses such variation and the debate about whether it arises from measurement error or definitions based on contemporary politics. No matter which view you might hold, it’s pretty clear that macroeconomic policy should not be based on early estimates of quarterly GDP growth.

Last month, the Bureau of Economics Analysis (BEA) reported that 2nd Quarter 2015 GDP had increased by 3.7% (in annualized terms.) Its first estimate (in July) was 2.3%. For the first quarter of 2015, we now have three estimates: earliest +0.2%, 2nd -0.7%, and most recent (August) +0.6%. In short, we can’t easily tell whether the economy grew or not.

Some of you may recall that GDP can be calculated in three ways: 1) the sum of what it would cost to purchase all goods produced in the US for final sale, 2) the income paid to all factors of production in the U.S. plus depreciation and indirect business taxes, and 3) the sum of all values added.

Typically no one calculates the third but recently, the BEA has begun to provide the income-based measure. For the first quarter of 2015, the second estimate was 0.4% after an initial estimate of 0.1%. For the second quarter of 2015, the only estimate of growth of gross domestic income was 0.6% (well short of the 3.7% GDP growth estimate cited above.)

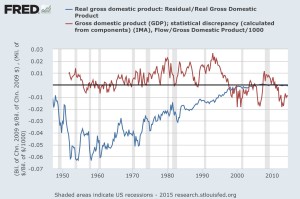

The difference between income based and expenditure based methods, as reflected by the residual (in red) in the above chart, is far from trivial. The blue line reflects gaps in converting nominal GDP to real GDP. These were substantial in the past, but appear not to be a problem today. See the St. Louis Federal Reserve’s discussion of this residual for details.

The difference between income based and expenditure based methods, as reflected by the residual (in red) in the above chart, is far from trivial. The blue line reflects gaps in converting nominal GDP to real GDP. These were substantial in the past, but appear not to be a problem today. See the St. Louis Federal Reserve’s discussion of this residual for details.

In a recent article entitled “Weapons of Economic Misdirection,” John Mauldin traces the history of GDP accounting and asks whether the changes reflect improved knowledge of the economy – such as updates to inventory, export, and import data – or political manipulation. Keynes and Hayek disagreed about what to measure and how it should be used, and Simon Kuznets, who created the national income accounts and received one of the first Nobel prizes in economics for his work, disagreed with the Commerce Department regarding the same two concerns.

Mauldin refers to and quotes from Diane Coyle’s new book GDP: A Brief But Affectionate History to illuminate the controversy. I encourage you to read Mauldin’s posting.

I’ll give Chinese Premier Li Keqiang the last word (especially with reference to the accuracy of Chinese GDP estimates – which seem to matter to many investors in the U.S.) “Chinese economic statistics are ‘man made’ and, apart from the numbers for electricity use, bank lending and rail freight, are for reference only.” Gives you great confidence, doesn’t it?