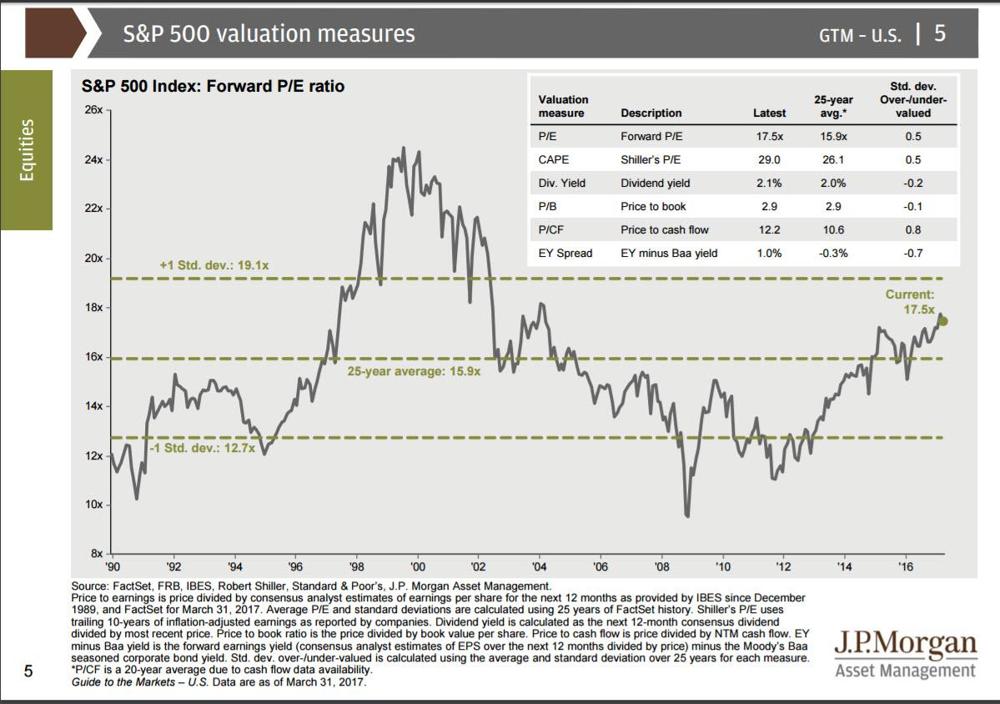

Each quarter J P Morgan, Inc provides a huge chartbook that one can use to characterize financial markets and the U.S. and global economies. Below is a sample chart on patterns and metrics for the S & P 500 index. Check them out.

Tag: Financial Crisis

Monetary Policy in an Age of Radical Uncertainty

Central bankers in all major developed economies have adopted NIRP, ZIRP, or near ZIRP policies. The Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank now “offer” negative interest rates (NIRP) on reserves and project to do so for the foreseeable future. The Bank of England and the Federal Reserve Bank of the United States remain committed to targeting interest rates slighted above zero (near ZIRP). 10 year government bonds offered by these countries range from -0.225% in Japan to -0.027% in Germany to 1.57% in the U.S. Such policies are not consistent with sustainable economic growth. See Professor Gerard’s previous posting on the pervasiveness of such interest rates.

In a recent book entitled The End of Alchemy, former Bank of England Governor Lord Mervyn King argues that the policies we have employed in the past (and present) to stabilize our economies – such as keeping interest rates low until economic growth returns to its long term rate or unemployment falls below some designated benchmark (full employment? natural rate of unemployment?) – are inconsistent with sustainable economic growth. Furthermore, he suggests that central bank and regulatory policies adopted post Great Recession (December 2007 – June 2009 in the U.S.) fail to address the potential for a repeat of the financial failures witnessed during that period. Among other points, King observes the following (for more in depth comments on King’s insights go here.)

- In the contemporary world economy, many shocks to the economy are unpredictable; thus, one cannot use probability-based forecasting models to design policy to stabilize economies. (King calls this radical uncertainty)

- Policies designed to stabilize economies in the short run, such as aggressive monetary and fiscal policies, leave a residue inconsistent with long run economic growth unless stagnation is viewed as the desired norm. For King, policymakers face the stark trade-off of short term stability for long term sustainable economic growth. In contrast to Keynes, in the long run, we are NOT all dead.

- In contrast with central banks as “lenders of last resort,” King offers the innovative idea of “pawnbroker for all seasons” as a constructive substitute. Banks would know in advance what their liquid assets will bring them in terms of central bank conversion to cash.

Each of the above points demonstrates how King views central banking and bank regulation in a world characterized by radical uncertainty. In short, policy makers need to find viable coping strategies to reduce the downside cost of economic recessions in general and financial meltdowns in particular. With radical uncertainty, the “forward guidance” offered by central banks lacks credibility and fails to address such uncertainty. In the words of Michael Lewis ( of Liar’s Poker, Moneyball and the Blind Side fame), “if his book gets the attention it deserves, it might just save the world.” (http://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2016-05-05/the-book-that-will-save-banking-from-itself)

The FOMC (Federal Reserve Open Market Committee) Meets at Lawrence

No, this is not April Fool’s Day. Tomorrow’s Money and Monetary Policy class will host Lawrence alum and Federal Reserve

Bank of Minneapolis’ First Vice President Jim Lyon (9 – 10:50, Briggs 217). During the first hour, Lyon will discuss the Dodd-Frank Financial Reform Act passed in 2010. He will detail how far along the implementation process is as well as what we can expect to happen.

During the second hour, Lyon will put on his “Ben Bernanke hat” and chair a shadow meeting of the FOMC. Students in the class will present the views of the other members of the Board of Governors of the Fed as well as those of the bank presidents of the 12 regional Federal Reserve banks.

You are welcome to attend these awesome proceedings.

The Fiscal Cliff Averted?

Yesterday, Congress passed legislation designed to avoid the strictures Congress enacted in the summer of 2011 to enable the United States government to borrow in excess of the existent debt ceiling. These provisions would have allowed the income tax cuts enacted in the George W. Bush era to expire as well as imposed spending limits on defense and discretionary non-defense spending.

There are numerous provisions in yesterday’s bill, summarized by the White House here. The Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimates the increased revenue from the bill to yield $62o over 10 years, far short of the 4 trillion dollars some estimate will be need to generate a sustainable level of debt. Furthermore, the debt ceiling and expenditure components of the “cliff” will remain subjects of political debate for at least the next two months when further action will be required. In short, we have “kicked the can down the proverbial road” again.

Bruce Bartlett, in a New York Times Economix posting yesterday, offers little in the way of enthusiasm regarding the political feasibility of making serious headway in addressing prospective budget deficits now and in the near future. His argument parallels the time inconsistency argument that earned Edward Prescott and Finn Kydland the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2004.

The Congress that raises taxes and cuts benefits will suffer politically, while the benefits of lower deficits will accrue to future Congresses.

He goes on to argue that

Historically, what has moved Congress to enact big deficit-reduction packages was the prospect of quick improvement in terms of inflation, growth and interest rates. Given that deficit reduction today is very unlikely to improve any of these in the near term, deficit hawks lack any real payoff from a grand bargain.

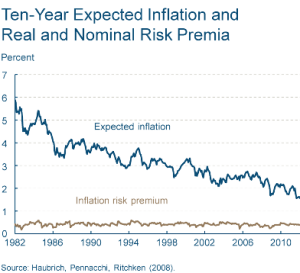

Inflation has been low and stable as has expected inflation.

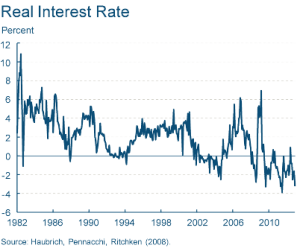

Even though expected inflation has been stable or declining for the past decade, real interest rates for treasuries (see chart below) – market rates minus expected inflation – has been negative for much of the past decade with the exception of the brief positive values in 2005 – 2007 and with expected deflation in late 2008. If real interests are negative, the crowding effects of public sector borrowing are non-existent; thus, the cost of running deficits has not “spooked” the markets. Of course, permanent negative real interest rates are not sustainable since few lenders will continue to offer their savings in exchange for reduced future consumption.

In the famous song from The Lion King, Hakuna Matata – there are no worries or no problem. Of course, such attitudes last only as long as those who lend money to the US government continue to do so. As Reinhart and Rogoff argue persuasively in This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, this time is not different. Financial excesses and repression eventually must be paid for. We just don’t know when or how severe the price will be.

ZIRP: The New Free Lunch? Don’t Bet on It.

The Federal Reserve Bank of the US has followed a zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) since fall 2008. It has employed a variety of mechanisms to lower not only overnight loans between banks (the Federal Funds rate – its usual target) but also to lower the entire yield curve. (See the details at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.) Previous postings here and here have addressed some of the costs of this approach.

Yesterday’s Financial Times contains some historical evidence consistent with the idea that ZIRPS are not free. John Plender argues that experience in Japan over two decades indicates that very low interest rate monetary policy did significant structural damage to the Japanese economy. In addition to creating a very low cost of capital, excessive monetary ease tends to lock-in the existing industrial structure or as he argues

“…from the Austrian perspective of Von Mises, Schumpeter, and Hayek, the Japanese bubble that burst in 1990 fostered economic distortions they dubbed ‘malinvestments’ – credit driven investments in real capital that prove loss making when a credit bubble implodes.”

As a consequence, Japan impeded “creatively destructive” economic activity since “zombie” companies were kept alive by cheap credit that was not available to new entrants. Capital allocation became very distorted; hence, many profitable opportunities were foregone and low return (perhaps even negative return) activities remained in existence.

Of course, that was Japan. Not the U.S. That couldn’t happen here, could it?

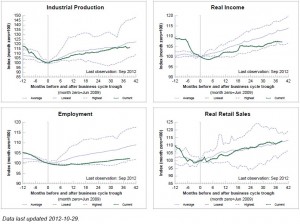

Economic Recovery: How Slow Has Our Recovery From the 2007-2009 Recession Been?

Much political debate – more appropriate described as hot or even toxic air – attempts to address how poorly the economy has recovered from what Reinhardt and Rogoff call The Great Contraction. As noted in Professor Gerard’s recent post, R and R argue– as they have done many times before – that recoveries from balance sheet or financial crisis recessions are much slower than those related to “garden variety” declines in aggregate demand. So what does the current recovery look like? One way to answer this is to view the four major indicators that the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Business Cycle Dating Committee uses to identify the beginning and ending points for recessionary and expansionary periods. Fortunately, our friends at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis have done all the hard work. As can readily be seen below (or more clearly here), industrial production and real retail sales have grown roughly in line with the average of past recessions. Real income started to grow similar to past history, but for the past 18 months growth has slowed markedly. The employment growth pattern, however, has shown the least responsiveness to the medicinal help provided by the Federal Reserve and other governmental policies. This suggests that “financial crisis” related recessions require both more time and different policies than demand deficient recessions not induced by too much debt. I will have more to say about why in future posts.

Regulating Wall Street: Did We Go Too Far?

Lawrence alum Elijah Brewer will address the above question in the next Economics Colloquium. It will take place next Monday, October 8th, in Steitz Hall 102 at 4:30. We encourage all to attend.

Brewer characterizes what he will argue as follows:

The causes of the financial crisis of 2007-09 are many and varied. Indeed, the crisis may be viewed as the product of a perfect storm. This address will discuss many of the popular causes of the U.S. crisis and enumerate their more important sins. It then presents the traditional way we like to think about commercial banks, and how that had changed leading up to the financial crisis. Indicators of stress in the financial system, and commercial banks in particular, are presented. What you will see is that many of these indicators were flashing red well before regulators got their hands around the problem. I will argue that it was not the lack of regulation, but a lack of will by regulators to enforce the rules that were already on the books. Thus, the government’s and Congress’s desire to regulate Wall Street is mis-placed. The banking industry does not need more regulation for the regulators to ignore when it’s convenient for them to do so, but we need a greater will by regulators to enforce the regulations that they do have. I will conclude by offering an assessment of the Dodd-Frank Act.

Simplicity vs. Complexity : It’s Not That Simple

Everyone knows that the Dodd-Frank law passed in 2010 to regulate the financial industry is incredibly complex. As those who took Money and Monetary Policy last fall learned from alum Jim Lyon, it will take years just to write the implementation provisions. Furthermore, these provisions will be influenced significantly by those (especially in the banking industry) whose behavior will be affected.

Andrew Haldane, in the most recent Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank symposium in an article entitled “The Dog and the Frisbee”, argues that such complexity is far from optimal in an economic environment in which uncertainty prevails. He uses the concept of uncertainty in the same way that Frank Knight and John Maynard Keynes did almost a century ago; that is, situations in which assessing the probability of different outcomes is quite low and that risk cannot be easily measured and therefore, hedged against. Haldane argues for simple rules, such as existed under the Glass-Steagall Act which forbids the mixing of commercial and investment banking.

In a recent blog entry on the EconoMonitor, Ed Dolan analyses this argument in terms of Goodhart’s Law, which suggests that as soon as a particular indicator becomes an explicit policy variable, it loses its predictive power because economic agents change their actions in response to expectations of the authorities using this indicator for policy action. Some of you might recall this as a variation of the Lucas critique of traditional monetary and fiscal policy actions.

All of the above is prologue for our next Economics Colloquium to be held next Monday. Our visitor, 1971 Lawrence alum, Elijah Brewer, will address the topic “Regulating Wall Street: Did We Go Too Far?” Be sure to come to his talk at 4:30 PM, Monday, October 8th in Steitz Hall 102.

A Gold Rush of Commentary

It seems the Republican party’s talk of a gold commission has led to a virtual gold rush of commentary from columnists, talking heads, and assorted punditry. Taking a glance at the Real Clear Markets link aggregator, I see “The Failing Case for Gold,” “The Top Ten Reasons you Should Support the Gold Commission,” and “GOP’s Golden Oldie,” along with the fabulously titled “The Lost Bush/Obama Era Gave Us the Gold Commission” and “The First Gold Commission Scared the Hell Out of the Fed. These latter two pieces with the provocative names are pretty favorable takes, I’d say.

Not every economist is high on the gold standard, as Paul Krugman noted a few years back:

There is a case to be made for a return to the gold standard. It is not a very good case, and most sensible economists reject it, but the idea is not completely crazy.

Most sensible economists, yes, suggesting that some sensible economists might be somewhat more favorable (see the links herein, for instance).

Of course, times change, and evidently so has Krugman’s assessment. Here’s Krugman’s in yesterday’s New York Times:

The truth is that returning to gold is an almost comically (and cosmically) bad idea.

So much for the sensible goldbug. Krugman finishes the piece with this zinger:

Now, the gold bugs will no doubt reply that under a gold standard big bubbles couldn’t happen, and therefore there wouldn’t be major financial crises. And it’s true: under the gold standard America had no major financial panics other than in 1873, 1884, 1890, 1893, 1907, 1930, 1931, 1932, and 1933.

I guess we’ll see how the campaign shapes up and perhaps we’ll be seeing more of this.

“Um, hello? Can I tell you about the real world?”

That’s hedge fund manager Hugh Hendry talking to Nobel-prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, as quoted in this Financial Times article.

See the exchange here. It gets interesting around 7 minutes for sure where Hendry suggests Greece will have to default or give creditors a “haircut” as it recognizes that it has unsustainable levels of debt.

But, back the FT piece, Hendry thinks we are on the verge of financial anarchy, that France will nationalize its banks, that China is hosed, that Japan is in trouble, and that the global debt situation is so dire that “the scale and the magnitude of the problem is greater than their (read: governments’) ability to respond.” He concludes that we are within ten years of an epic financial collapse reminiscent of the 1930s.

The good news?

The US isn’t as bad off as Brazil, India, Russia, and China. And that the financial collapse will create investment opportunities of a lifetime.

Have a good weekend.

“This dwarfs by orders of magnitude any financial scam in the history of markets”

The LIBOR scandal is all over the financial press, and as the headline here indicates, it might be a big deal. Typically, when you see a quotation like that, it is from a blogger residing in his parents’ basement. In this case, however, the source of the quote happens to be MIT distinguished professor Andrew Lo.

And he’s not alone.

Former New York governor Eliot Spitzer seems to concur, saying that “LIBOR is huge. This is about as big as it gets in the financial world.”

So, what is this all about?

Essentially, it appears that a group of traders colluded to set the LIBOR rate, an interest rate that is at the center of international financial markets, over the course of several years. Indeed, roughly $800 trillion in financial instruments are tied to LIBOR. A second issued now gaining traction is that it is possible that U.S. regulators knew about this years ago.

Both cases seem to undermine the integrity of financial markets generally, and that is simply not a good thing in terms of linking up savings and investment.

Here is a helpful infographic from AccoutningDegree.net. Not to be outdone, here is another helpful infographic via the New York Times.

You will probably be reading about this one for some time. I liked this piece in The Economist, which takes a forward look at these “Banksters.” I also really liked this piece from Ed Dolan on why LIBOR rates were subject to manipulation — motive, means, and opportunity.

Columbo couldn’t have said it better himself.

A Remarkable Fact

Continuing our string of posts about the EU, here is a remarkable but perhaps unsurprising fact: Since gaining its independence in 1829, Greece has defaulted on or rescheduled its external debt five times (1826, 1843, 1860, 1893, and 1932). Greece has been in default roughly half the time period since 1829.

That is culled from the astonishing This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly from Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff.

I’m finally plowing through some of summer reading recommendations. This particular recommendation was from 2010.

The Good Ol Summit Time

As summer marches on, the financial situation in Europe remains unresolved, some economists are arguing that a devaluation and subsequent inflation of the Euro is in order (see Kenneth Griffin and Anil Kashy here and Martin Feldstein here). The Grumpy Economist, University of Chicago’s John Cochrane, is skeptical and provides a helpful analogy:

Imagine that your brother in law had been drinking too much for 40 years, perpetually on and off the sauce, never really able to give it up. He went through a painful 12 step program and rehab, and finally quits the sauce for 10 years. He threw away all the liquor in the house. Then he loses his job. Is “one more big night out to soothe the pain, and then I’ll really really never do it again” at all a credible plan? That’s exactly what my normally sensible colleagues (see above) are advocating.

My guess is that most of our readership does not have brother-in-laws who have been drinking too much for 40 years, so I will give you something closer to home.

Back when I was in college I had a friend who tended to fall behind a bit in his classes, something like accumulating large piles of debt. At some point, of course, the debt would mount and he would reach a crisis situation, forcing him to face some unpleasant facts. He would then of course have to develop a plan to “restructure” the debt — for instance, does this sound familiar?, getting an extension on a paper, strategically dropping a class, deciding which course he could get by without studying, etc… And, remarkably, once the plan was in place, he would have some sort of celebration even prior to completing any of the work he had to do.

To my knowledge, he had no way of credibly committing to putting the plan in place. What I mean by that, of course, is that he generally didn’t put the plan in place.

I’m not sure whether he ever graduated, but I do know that he has been a very successful entrepreneur. I’m not sure exactly what that does for our analogy.

On a not entirely unrelated note, Kevin “Angus” Grier at the Kids Prefer Cheese blog provides some visual insight in the salubrious effects of European summits on financial markets.

It’s summit time!

Monday Quiz

For this week’s Monday quiz we ask you this — Do these quotations refer to

- The current state of country finances, or

- The strength of the respective football teams competing in the Euro 2012 tournament?

Via Justin Wolfers.

What Should Central Bankers Do?

No, this is not a question on the final exam for Money and Monetary Policy; however, it has been. It’s also a question that pervades contemporary political economy in the US and Europe.

Federal Reserve Chair, Ben Benanke continues to be criticized from both those who advocate aggressive monetary policy and those who argue that the Fed has been too aggressive. For example, today’s Wall Street Journal features “Fed bashing” from the House Financial Services Committee.

The Fed’s easy-money policy and actions taken to boost economic growth have prevented lawmakers from taking responsibility for shoring up the economic recovery and reducing the deep federal budget deficit, some Republicans said Tuesday at a hearing of a panel of the House Financial Services Committee.

“As the Fed does more, Congress is doing less and in the long term that slows our recovery,” said Rep. Kevin Brady (R., Texas).

How are we to interpret this? Mr. Bernanke, since you did your job appropriately, we won’t (can’t?) do ours?? Of course, many pundits, especially those who fear a tripling of the Fed’s balance sheet since 2008, believe that the world would be better without the Fed. Anyone ever heard of Ron Paul?

At the other extreme, Paul Krugman, not to be outdone in the world of political rhetoric Earth to Bernanke, has accused Fed Chair Bernanke of not following the advice that Professor Bernanke gave the Japanese in a 2000 paper. He and others such as Scott Sumner of the Modern Monetarist Movement argue that the Fed should target nominal GDP and make monetary policy as expansionary as needed to reach that target.’

Where’s the center or at least some non-extreme view? I suggest one look to Raghuram Rajan who yesterday posted “Central Bankers Under Siege” and for the current issue of Foreign Affairs wrote “True Lessons of the Recession.” In these articles, Rajan argues that various versions of demand stimulus through credit creation will not address fundamental structural problems in the US economy. He concludes the latter article as follows:

The industrial countries have a choice. They can act as if all is well except that their consumers are in a funk and so what John Maynard Keynes called “animal spirits” must be revived through stimulus measures. Or they can treat the crisis as a wake-up call and move to fix all that has been papered over in the last few decades and thus put themselves in a better position to take advantage of coming opportunities. For better or worse, the narrative that persuades these countries’ governments and publics will determine their futures — and that of the global economy.

So, what should Central Bankers do? In my view, they should recognize that monetary policy has its limits and that using monetary policy as a means to generate sustained employment won’t work. Longer term structural adjustments are required. Such adjustments will be the subject of another blog posting.

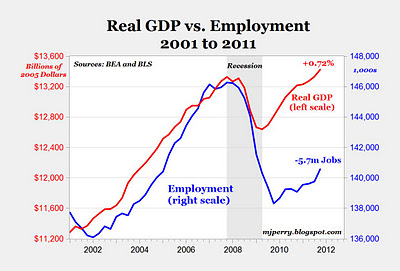

GDP Growth vs. Employment Growth

At last, the level of real GDP has rebounded past its previous peak in the fourth quarter of 2007. Clearly, the trough for employment was both much deeper and trailed that for GDP. In contrast, the recovery for real GDP has been more rapid as well. Financial repression (extremely low interest rates) must be part of the story behind this chart. Clearly, an increased cost of labor relative to capital induced a capital intensive recovery.

At last, the level of real GDP has rebounded past its previous peak in the fourth quarter of 2007. Clearly, the trough for employment was both much deeper and trailed that for GDP. In contrast, the recovery for real GDP has been more rapid as well. Financial repression (extremely low interest rates) must be part of the story behind this chart. Clearly, an increased cost of labor relative to capital induced a capital intensive recovery.

Low Interest Rates: the Addictive Policy Drug of Choice

Satyajit Das, in today’s Financial Times, argues that low interest rates generate a variety of economic distortions that expand rather than address structural problems in economies (whether those of the U.S., Europe, or elsewhere.) These effects are especially pernicious when real interest rates (that is market interest rates minus the expected inflation rate) are negative. He provides a laundry list of “side effects” to this economic drug of choice.

1. Encourages the substitution of capital for labor. Is it any surprise that employment has been slow to respond eventhough GDP is now higher than it was at the beginning of the last recession?

2. Encourage the substitution of debt for equity funding

3. Discourage savings, especially when real rates are negative. Of course, if households have a particular wealth target, low rates could induce additional savings.

4. Create a funding gap for defined benefit pension plans (which means either reduced benefits or attempts to increase returns through more risky financing)

5. Feed asset price inflation through the purchase of risky assets (related to point 4)

6. Reduce the cost of holding money (which inhibits the flow of capital to worthwhile activities)

7. Allow banks to borrow cheaply (from depositors) and achieve their income targets through purchase of governmental securities rather than through lending to the private sector

8. Distort currency values as deviations in interest rates across countries is one of the drivers of short term capital flows

9. Induce a reliance on low interest rates to continuously fuel aggregate demand

For the most part, those who argue for extended periods of low interest rates believe that aggregate demand drives aggregate output. They tend to underplay the importance of structural change in the economy (such as labor market, regulatory, or tax policy reform); such change cannot be addressed by replacing depressed elements of aggregate demand with policy induced aggregate spending. The day of reckoning is just extended, not cancelled. Just ask the Europeans.

Our Macroeconomic Future: A Chaos Theory for Investors.

Neel Kashkari, managing director and head of global equities for PIMCO, has recently posited an array of possible scenarios for America and Europe and employs a simplified version of chaos theory to sort through the results. Kashkari was Secretary of Treasury Hank Paulson’s assistant; he worked directly with implementing the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP.) He plays a significant role in Andrew Ross Sorkin’s book Too Big to Fail. The movie, starring William Hurt, does a nice job reflecting the book.

Western economies (mostly governments and households) have loaded themselves with debt that under most scenarios is not sustainable. Kashkari indicates the following five options policy makers have as well as the potential consequences for investors. Check out his analysis.

1. Austerity and deflation

2. Explicit default

3. Mild inflation

4. Runaway inflation

5. Miraculous growth

Which scenario do you think is most plausible? Least plausible? Do your answers differ for the U.S., Europe, and Japan? Why or why not?

Johnson on Stigler on Regulation

Simon Johnson is the co-author of 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown, which we wrote about here. This week, Russ Roberts interviews Johnson on EconTalk, and a summary of the interview. Here’s a taste:

On Regulatory Capture: Prof. Johnson says he is a follower of George Stigler, who made the point that when you regulate industry, industry will attempt to capture the regulators. Bankers are able to capture the regulation and get themselves huge commissions to take on risk. We witnessed one of the most sophisticated episodes of regulatory capture in the history of humankind.

On who benefitted: The benefit of this kind of rent-seeking accrues to executives in the bank – and not to shareholders.

Interesting point, that we also brought up here.

Jim Lyon and the World of Money and Banking

Thursday, you will have two opportunities to engage with Jim Lyon, Lawrence alum and First Vice President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. He will be discussing “Too Big to Fail” and the Dodd-Frank Act response at 9:00 in Money and Monetary Policy (Briggs 225). He also will chair a mock Federal Open Market Committee meeting in which students in the course will represent members of the Board of Governors and Presidents of the 12 district Federal Reserve Banks. You are welcome to join us for either part of the class.

At 4:30, we will have an Econ Tea with Mr. Lyon as well. This will be an open and free-wheeling session for which the topic will be “Everything you always wanted to know about money and banking and ARE NOT afraid to ask.” Come for the discussion or just come for the cookies and tea.