![]() For those of you driving somewhere for Reading Period, or for those of you who simply have trouble reading, Tim Harford offers up the best in economics podcasts, including the Financial Times podcasts.

For those of you driving somewhere for Reading Period, or for those of you who simply have trouble reading, Tim Harford offers up the best in economics podcasts, including the Financial Times podcasts.

Stuck in The Mudd

Looking to pick up some reading recommendations for the upcoming Reading Period? My pick is Tyler Cowen’s e-book, The Great Stagnation, which has been something of a sensation since its release (if by sensation you mean, which I do, a bunch of economists and policy wonks have been reading and reviewing it). Plenty of buzz about this one, and at $4, it is about the price of a magazine.

Looking to pick up some reading recommendations for the upcoming Reading Period? My pick is Tyler Cowen’s e-book, The Great Stagnation, which has been something of a sensation since its release (if by sensation you mean, which I do, a bunch of economists and policy wonks have been reading and reviewing it). Plenty of buzz about this one, and at $4, it is about the price of a magazine.

Just not that into Stagnation? We’ve got more. Professor Finkler also just recommended a slew of books to me, including these:

- Amar Bhide’s Call to Judgment

- Raghuram Rajan’s Fault Lines (see Professor Finkler’s brief comments here)

- Nouriel Roubini’s Crisis Economics: A Crash Course in the Future of Finance

- Baumol, Litan, and Schramm’s Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism

Most of these are stocked over on the shelves of The Mudd (subject to availability, of course), along with a constant stream of tasty new releases. Just scanning that RSS feed, I see Michael Lewis’ breezy The Big Short as an appetizer(library info; more on Lewis here). And the fascinating-looking title ![]() Entrepreneurship, innovation, and the growth mechanism of the free-enterprise economies edited by Sheshimski, Strom, and Baumol could be a very enticing main course. I might just go run that one down.

Entrepreneurship, innovation, and the growth mechanism of the free-enterprise economies edited by Sheshimski, Strom, and Baumol could be a very enticing main course. I might just go run that one down.

You might consider adding to that list Branko Milanovic’s new book, The Haves and the Have-Nots (discussed here), that I plan to order presently.

For those of you who only do things for credit, there is a rumor floating around the department that as a follow up to the Schumpeter Roundtable, we will be Discovering Kirzner by reading Israel Kirzner’s Competition and Entreprenuership this Spring term. It was also recently announced that the Spring Lawrence community read will be Cheap: The High Cost of Discount Culture. Professor Galambos and I are both signed up for that one.

Finally, I am right in the middle of Steven Johnson’s Where Good Ideas Come From, which my colleagues mostly seem to like. Something you can probably read in the car, if it wasn’t for the 6-point font footnotes.

Enjoy!

New Course

A new course possibly of interest to many of you will be offered next term. It was not on the books when you registered, so we are trying to let you know about it:

History 376: International Development in Historical Perspective

History of economic development theory, policy, and practice throughout the world since 1945. Particular focus will be given to the evolution of orthodoxy in this field, from modernization theory through dependency theory to neoliberalism, considering the performance and criticism of each. Case studies include African, Asian, and Latin American countries.

Taught on TR 12:30, the course requires sophomore standing and has no other prerequisites. It is taught by Michael Mahoney, a specialist on the history of Africa who taught at Yale for a decade (including this course).

Schumpeter Birthday Convocation

Mary Jane Jacob’s convocation lecture, “The Collective Creative Process,” is Tuesday at 11 at the Lawrence Chapel. Here is the lowdown:

Jacob is an independent curator known for her innovative, creative and collaborative projects Executive Director of Exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago, Jacobs has published many books and articles that examine ways to more fully involve the community into contemporary art by moving art out of “dead” museums and galleries into “living” spaces. Her work began in the early 1990s with the “Places with a Past” exhibition in Charleston, SC where she collaborated with 23 artists who each set up a public installation in Charleston in an attempt to tell the history of the city.

A scouring of the internet tells me that Jacob’s “name is synonymous with the phrase ‘art as social practice’ or the field of art that is now more widely known as ‘Relational Aesthetics.'” What that means, I am sure we will find out.

It is perhaps fitting that a faculty convocation celebrating “Innovation through Collaboration” coincides with the birthday of economist Joseph Schumpeter, who certainly needs no introduction on this blog.

But, of course, I am happy to give you one anyway.

Enjoy the Convo!

Jobs (slightly up) and the Unemployment Rate (downward trend)

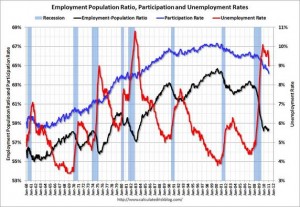

Last Friday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the unemployment had fallen to 9.0%, a sizable drop from December’s 9.4% and November’s 9.8%. The BLS also released the payroll survey which indicated that the number of employed based on the non-farm payroll survey only increased by 36,000 in January. Such a small increase fails to keep up with trend labor force growth which averages about 125,000 per month (based on a civilian labor force of roughly 150 million that grows at about 1% per year.)

So is this good news or bad news? Actually, these two results are largely unrelated to one another. The unemployment rate is derived from a household survey which also revealed that the number of employed people rose by 117,000, that is almost the trend rate. The payroll survey tends to look at relatively older companies, which typically do not drive employment growth. James Hamilton, in a recent Econbrowser piece, lays out some of the relevant details. The chart below highlights key labor market patterns. The relatively low level of labor force participation puts downward pressure on the unemployment rate, which is why that indicator is not particularly informative with regard to the JOBS, JOBS, JOBS agenda. The details will entertain those of you who will take Econ 320 next term.

Blackout is Another Word for “Shortage”

No doubt you have heard (okay, perhaps I have some doubts) about the blackouts rolling across Texas this past week. Blackouts occur, of course, because the quantity of power demanded at a point in time exceeds the quantity of power supplied, leaving some folks literally in the dark. And out in the cold.

So, the key question is why power supply was insufficient. Michael Gilberson of Texas A&M provides a preliminary analysis of why Texas power producers failed to meet demand. The first reason is that it was very cold, so the demand for power increased. The cold also caused the power to decrease (!) as power plants themselves suffered outages due to frozen pipes at large coal-fired plants (didn’t their mothers ever tell them to leave the water dripping?).

Actually, that isn’t really the first reason. The real reason is likely Texas’ famous electricity isolationism; that is, the state deliberately lacks to infrastructure to export or to import electricity. Why would they pursue such a policy? To avoid federal (i.e., inter-state) regulation.

Here’s another explanation along the same line.

That electricity markets tend to be very complicated to understand, but supply and demand fundamentals are not.

Local Sports Team in Contest of Interest

The pride of the Fox Valley, the Green Bay Packers, will be mixing it up with my former hometown heroes, the Pittsburgh Steelers, at the Super Bowl. The game will take place, weather permitting, this Sunday in balmy Dallas, Texas.

Although the contest itself is predominantly of interest to denizens of northeastern Wisconsin and southwestern Pennsylvania, many from across the nation and around the world will tune in for antics of the mascots (pictured), the often-irreverent commercials, the many wagering opportunities, or simply as an excuse to feast on some tasty snacks (despite some unexpected side effects). Yum.

This year, we are also treated to some added intrigue by a number of touching personal-interest stories. Or if you aren’t into Olympics-coverage style tearjerkers, perhaps you’d like to see how some famous movie directors have portrayed the Big Game.

Econ majors might be interested in some of the simple economics of the Super Bowl (summary here), such as secondary-market ticket prices (more than you think) and estimated economic impacts (less than you think). You might also be interested to know that Green Bay punter Tim Masthay abandoned a lucrative career as an economics tutor at the University of Kentucky, where “he picked up anywhere from three to six hours a day as a tutor, helping student athletes … with economics and finance courses. That paid $10 an hour.”

$10 an hour? Not bad.

My allegiances here are more with the black-and-gold than the green-and-gold. Indeed, earlier this year communications director Rick Peterson introduced me as “a big Steelers fan,” so there you have it. I also made a friendly wager with Professor John Brandenberger on the outcome of the game (even spotting him the three points that the Packers were favored by at the time of the bet). I have a feeling I’m going to be buying over at Lombardi’s.

Though my heart is with the Steelers, I’m guessing that the general spirit of the community and quality of the celebratory culinary fare will be better with a Packers win.

Federal Spending — Actual and Affordable

Political Calculations has another wonderful, self-explanatory graphic:

Great blog. I’m going to add it to my recommendations.

Economics SpecialTea w/ Dave Mitchell

Update: World Still Not Flat (at least not income distribution)

The New York Times reviews The Haves and the Have-Nots, what appears to be a fascinating new book from World Bank economist, Branko Milanovic. In addition to the review, the Economix blog features this extraordinary representation of world income distribution by country:

Milanovic has broken income (adjusted for purchasing power) by country down into twenty “ventiles.” So the lowest five percent of income earners are in the first ventile and the richest five percent are in the top ventile. What this piece shows is that the poorest of the poor in America are in the 70th percentile of world income. Compared with India — the average American in that first ventile has as much income (adjusted for purchasing power) as the richest Indian ventile.

I find that astonishing.

I also note with interest that there is a very steep ascent of the American distribution, indicating the poor here are really, really poor in relative terms, but the rest of the country is in pretty good shape. The median income in the US in comfortably in the top 10% of world income.

Well, I’m pretty happy, but maybe that’s just me.

America Unhappier, Death and Divorce Make People Sad

Professor Gerard recently wrote about the views of Schumpeter and Stigler on Intellectuals. In the paper he cites, Stigler wonders why Intellectuals hate economics, and considers the possibility that our extremely technical field and extremely poor communication style might have something to do with it:

Less than a century ago a treatise on economics began with a sentence such as, “Economics is a study of mankind in the ordinary business of life.” Today it will often begin: “This un- avoidably lengthy treatise is devoted to an examination of an economy in which the sec- ond derivatives of the utility function possess a finite number of discontinuities. To keep the problem manageable, I assume that each individual consumes only two goods, and dies after one Robertsonian week. Only elementary mathematical tools such as topology will be employed, incessantly.” (Stigler: The Intellectual and the Market Place)

A paper I looked at recently reminded me of another reason why many Intellectuals look askance at us economists: the long and solid tradition of “economic imperialism.” That is, the tendency of a number of economists to think that our economist’s toolbox can be (and should be!) used to explain just about anything that reasonably falls under the heading “social science.” The paper I referred to is Well-Being Over Time in Britain and the USA by David Blanchflower, and the abstract includes this:

Money buys happiness. People care also about relative income. Wellbeing is U-shaped in age. The paper estimates the dollar values of events like unemployment and divorce. They are large. A lasting marriage (compared to widow-hood as a ‘natural’ experiment), for example, is estimated to be worth $100,000 a year.

I agree that research on happiness is very much relevant to economics, but I can just see a psychologist or a sociologist or a humanist read that and not know whether to laugh or to cry. (And what’s up with talking like Tarzan?) Blanchflower looks at survey data (essentially asking people whether they are happy or not) over the past few decades and then runs a bunch of regressions. There is nothing wrong with that, except for a dozen issues that cast doubt on the conclusions and that have probably been the subjects of extensive research in psychology, sociology, history, and maybe even economics. Without passing judgment on Blanchflower (about whom I know nothing), I am pretty confident in saying that a number of papers in economists have been guilty of applying economic tools to broader problems without bothering to understand the broader literature (you know, what those “soft” social scientists write).

Pro-Market v. Pro-Business

George Mason economist, and letter-to-the-editor writer extraordinaire, Don Boudreaux, has an opinion-editorial in the Christian Science Monitor explaining his distinction between public policies that are pro-business and those that are pro-market.

Economists (especially the free-market variety) – concerned always to keep outputs of goods and services as high as possible – typically defend business against counter-productive government interference. We economists do so, however, not because we have special fondness for business. We do so because we understand that government interference in business often results in fewer goods and services for ordinary men and women – as consumers – to enjoy.

In short, an economy’s success is best measured by how well it pleases consumers, not by how well it pleases businesses…

“Competition” sounds good. But businesses don’t like competition; they like protection from competition – along with subsidies, special tax breaks, and other government favors that relieve them from the need to cater energetically to consumer demands. So a pro-business president is prone to curry favor with businesses by shielding them from competition…

The irony is that such policies – which really should be labeled “crony capitalist” – are often labeled “competitiveness” policies. Because these policies increase the profits of some domestic businesses, they are mistakenly believed to make the domestic economy more “competitive” when, in fact, they make it less so.

This seems to me to be an important distinction. I try to convey to you all that no one hates competition more than business does. If you set up a profitable business, say, selling hot dogs on a street corner, the absolute last thing you want is a competitor to park her cart next to yours.

And, while we’re on the subject, don’t forget to join us for tea at 4:21 for Econ TeaBA.

The Intellectual and the Marketplace — Schumpeter & Stigler

Having dispensed with the ever-dynamic Marx, the Schumpeter Roundtable continues through Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy this week with a close read of Part II — Can Capitalism Survive? After some wonderful writing on Creative Destruction in Chapter VII, we move on to the projected demise of capitalism, oh, sometime in the next 100 years or so. (Of course, this was published in 1942, so we could still be on schedule). In Chapter XIII we are faced with “Growing Hostility,” and Schumpeter provides us with some rather inflammatory views of the “The Sociology of the Intellectual.” To wit, Schumpeter contends that “unlike any other type of society, capitalism inevitably and by virtue of the very logic of its civilization creates, educates, and subsidizes a vested interest in social unrest.”

That vested interest, of course, is the intellectual. It is not my purpose here to endorse or to attack Schumpeter’s views (is he analyzing or just venting?), but rather to point to George Stigler’s concise “The Intellectual and the Market Place” as another giant of the profession trying to come to terms with why intellectuals seem — at least to these authors — to be be hostile to market economies. Continue reading The Intellectual and the Marketplace — Schumpeter & Stigler

Book on Inequality Makes The Economist Sick

In response to my post on The Spirit Level, Oscar Koberling pointed out in an email that the most recent issue (pronounce that with an “s”, not “ishue”) of The Economist includes a Special Report on “The Few” (not the proud, but the rich). One article in that Report beats up pretty effectively on The Spirit Level. Thanks for the tip!

Several articles in the Report are interesting. One of them is on higher education, and it points out that “[i]n some of the hardest disciplines most postgrads at American universities are foreign: 65% in computing and economics, 56% in physics and 55% in maths…”

You Can’t Cut the Internet ‘Signal’

There seems to be a very tumultuous situation in Egypt. In the face of mass protests being labeled “Angry Friday,” Jeff at the Cheap Talk blog and Tyler Cowen at Marginal Revolution assess the strategic implications for both protesters and for the government.

Here’s Jeff:

The decision to get out and protest is a strategic one. It’s privately costly and it pays off only if there is a critical mass of others who make the same commitment. It can be very costly if that critical mass doesn’t materialize.

Communications networks affect coordination. Before committing yourself you can talk to others, check Facebook and Twitter, and try to gauge the momentum of the protest. These media aggregate private information about the rewards to a protest but its important to remember that this cuts two ways.

If it looks underwhelming you stay home, go to work, etc. And therefore so does everybody who gets similar information as you. All of you benefit from avoiding protesting when the protest is likely to be unsuccessful. What’s more, in these cases even the regime benefits from enabling private communication, because the protest loses steam. Continue reading You Can’t Cut the Internet ‘Signal’

Inequality makes everyone sick

Last time we met for the Schumpeter Roundtable tutorial, we discussed Schumpeter’s point that perhaps the greatest strength of capitalism is that it provides precise, prompt, exact and effective incentives in the promise of great riches and the threat of great destitution. He would know, having been on both ends of that spectrum (well, almost). That sort of system has inequality built into it—inequality that serves an important purpose, some would say. A discussion on inequality and progress ensued, with spiritual, moral, economic, and technological dimensions, eventually leading one participant to remark that “going to Best Buy is a spiritual journey!” But there is, of course, a serious question: Is inequality good for a society (in the long run)? Or, to put it in terms of a trade-off, how much inequality is best? Tonight Tom Ashbrook on NPR spoke with UK Professors Pickett and Wilkinson, authors of The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. The book is based on research that shows, the authors claim, that more equal societies always do better in a number of ways, including overall population health. They argue that more equal societies are even more innovative, contrary to what Schumpeter might say about the importance of incentives in driving progress. As Professor Gerard has pointed out, economists do think about inequality and its consequences, and this book may add evidence to one or both sides. One member of the Schumpeter Roundtable argued that there is so much inequality in the US today, that most people are too discouraged to try hard to reach the top. This book seems to support that argument. Contrast that with Adam Smith’s view that the great driving force of economic development is the extraordinary effort of “[t]he poor man’s son, whom heaven in its anger has visited with ambition,” struggling to attain riches in the (erroneous) belief that money can buy happiness.

Last time we met for the Schumpeter Roundtable tutorial, we discussed Schumpeter’s point that perhaps the greatest strength of capitalism is that it provides precise, prompt, exact and effective incentives in the promise of great riches and the threat of great destitution. He would know, having been on both ends of that spectrum (well, almost). That sort of system has inequality built into it—inequality that serves an important purpose, some would say. A discussion on inequality and progress ensued, with spiritual, moral, economic, and technological dimensions, eventually leading one participant to remark that “going to Best Buy is a spiritual journey!” But there is, of course, a serious question: Is inequality good for a society (in the long run)? Or, to put it in terms of a trade-off, how much inequality is best? Tonight Tom Ashbrook on NPR spoke with UK Professors Pickett and Wilkinson, authors of The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. The book is based on research that shows, the authors claim, that more equal societies always do better in a number of ways, including overall population health. They argue that more equal societies are even more innovative, contrary to what Schumpeter might say about the importance of incentives in driving progress. As Professor Gerard has pointed out, economists do think about inequality and its consequences, and this book may add evidence to one or both sides. One member of the Schumpeter Roundtable argued that there is so much inequality in the US today, that most people are too discouraged to try hard to reach the top. This book seems to support that argument. Contrast that with Adam Smith’s view that the great driving force of economic development is the extraordinary effort of “[t]he poor man’s son, whom heaven in its anger has visited with ambition,” struggling to attain riches in the (erroneous) belief that money can buy happiness.

Bilateral Trade Numbers Are Misleading At Best

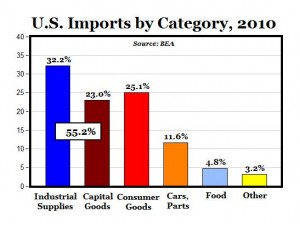

On January 13, 2011, The Bureau of Economic Analysis in the the U.S. Department of Commerce reported that as of November 2010, the U.S. trade deficit with China for 2010 amounted to $252 billion. This number tells very little about the character of trade between the two countries. It just captures the difference in final sales value of exports minus imports. Pascal Lamy, director-general of the World Trade Organization, argues in today’s Financial Times that manufacturing products developed through a global supply chain of steps should be labeled “made globally.” His comments include the notion that the Apple iPhone contributed $1.9 billion to the recorded US trade deficit with China, but that the value added in China from this product would come to only $73 million. Other analysts have shown that the value added in China comes to less than half of the trade balance number published.

Furthermore, the Bureau of Economic Analysis published a report indicating that 55% of our imports are used in the U.S. to produce domestic goods and services. Stated differently, these imports enable our companies and workers to be both productive and profitable.

Discussion of trade deficits without these detailed clarifications at best misinforms the public as to the economics of globalization; at worst, it encourages us to close our borders to (some) imports which would lead to both higher domestic prices and lower domestic output. The effects on employment would be complicated but not positive in the aggregate.

The Principals are Your Pals

I’m a bit behind on both my reading and on updating this blog, so I wanted to point to a series of fascinating articles at David Warsh’s Economic Principals blog. The first resulted from his trip to Denver for the American Economic Association meetings in early January, where he sensed a possible resurgence of interest in the history of economic ideas. This possibly rings true for those of us plodding through Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy this term.

Warsh followed up this dispatch from the AEA meetings with a most interesting piece on how the big brains of the profession are thinking about technological innovation and climate change. The piece starts with another dispatch from Denver, and traces its way back through the cold war to the RAND Corporation (and one of my heroes, Armen Alchian) and beyond. The piece touches on the contributions of Kenneth Arrow and Richard Nelson, now are both familiar names to anyone interested in the economics of innovation.

And if that’s not enough, this week’s column looks at Paul Samuelson and hedge funds, another hat tip to the history of thought that includes David Ricardo’s Waterloo. If nothing else, the blog seems to get its principals right.

I also continue to recommend Warsh’s Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery — an excellent pick for the summer reading list.

The New New Regulatory State

Earlier this week, President Obama penned an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal about his Administration’s plans for the regulatory state. The executive branch, as its title suggests, is in charge of executing and administering the laws of the land, and the President expresses his desire to balance the free-market innovation machine while protecting public health and safety:

[C]reating a 21st-century regulatory system is about more than which rules to add and which rules to subtract. As the executive order I am signing makes clear, we are seeking more affordable, less intrusive means to achieve the same ends—giving careful consideration to benefits and costs. This means writing rules with more input from experts, businesses and ordinary citizens. It means using disclosure as a tool to inform consumers of their choices, rather than restricting those choices. And it means making sure the government does more of its work online, just like companies are doing.

As my students learn in 240, 280, and 271, the executive branch, through the Office of Management and Budget, (potentially) plays a central role in shaping regulations as they make their way through the rulemaking process. Indeed, President Reagan issued the seminal executive order concerning benefit-cost analysis, and each President since has attempted to put his stamp on the process.

Of course, there is often a disconnect between what politicians say and what regulators actually do, here are a couple of other takes from a pair of scholars who spend more than their fair share of time thinking about administrative regulation: Stuart Shapiro and Lynne Kiesling.

Capitalism and Friedman

Yesterday was the 50th anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address that exhorted Americans to “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.” Although the expression is iconic and emblematic of the selfless nature of public service, not everyone was impressed. Indeed, free-market champion Milton Friedman opens his libertarian polemic, Capitalism and Freedom, with this:

IN A MUCH QUOTED PASSAGE in his inaugural address, President Kennedy said, “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.” It is a striking sign of the temper of our times that the controversy about this passage centered on its origin and not on its content. Neither half of the statement expresses a relation between the citizen and his government that is worthy of the ideals of free men in a free society. The paternalistic “what your country can do for you” implies that government is the patron, the citizen the ward, a view that is at odds with the free man’s belief in his own responsibility for his own destiny. The organismic, “what you can do for your country” implies that government is the master or the deity, the citizen, the servant or the votary. To the free man, the country is the collection of individuals who compose it, not something over and above them. He is proud of a common heritage and loyal to common traditions. But he regards government as a means, an instrumentality, neither a grantor of favors and gifts, nor a master or god to be blindly worshipped and served. He recognizes no national goal except as it is the consensus of the goals that the citizens severally serve. He recognizes no national purpose except as it is the consensus of the purposes for which the citizens severally strive.

The free man will ask neither what his country can do for him nor what he can do for his country. He will ask rather “What can I and my compatriots do through government” to help us discharge our individual responsibilities, to achieve our several goals and purposes, and above all, to protect our freedom? And he will accompany this question with another: How can we keep the government we create from becoming a Frankenstein that will destroy the very freedom we establish it to protect? Freedom is a rare and delicate plant. Our minds tell us, and history confirms, that the great threat to freedom is the concentration of power. Government is necessary to preserve our freedom, it is an instrument through which we can exercise our freedom; yet by concentrating power in political hands, it is also a threat to freedom. Even though the men who wield this power initially be of good will and even though they be not corrupted by the power they exercise, the power will both attract and form men of a different stamp.

Well, that’s a take I didn’t hear in my civics classes.

I was reminded of this in a recent discussion of theory of advocacy revolving around Schumpeter and Marx, where Friedman’s name came up. Schumpeter fleshes out the implications of science and ideology in his brilliant 1948 address to the American Economics Association, “Science and Ideology.”