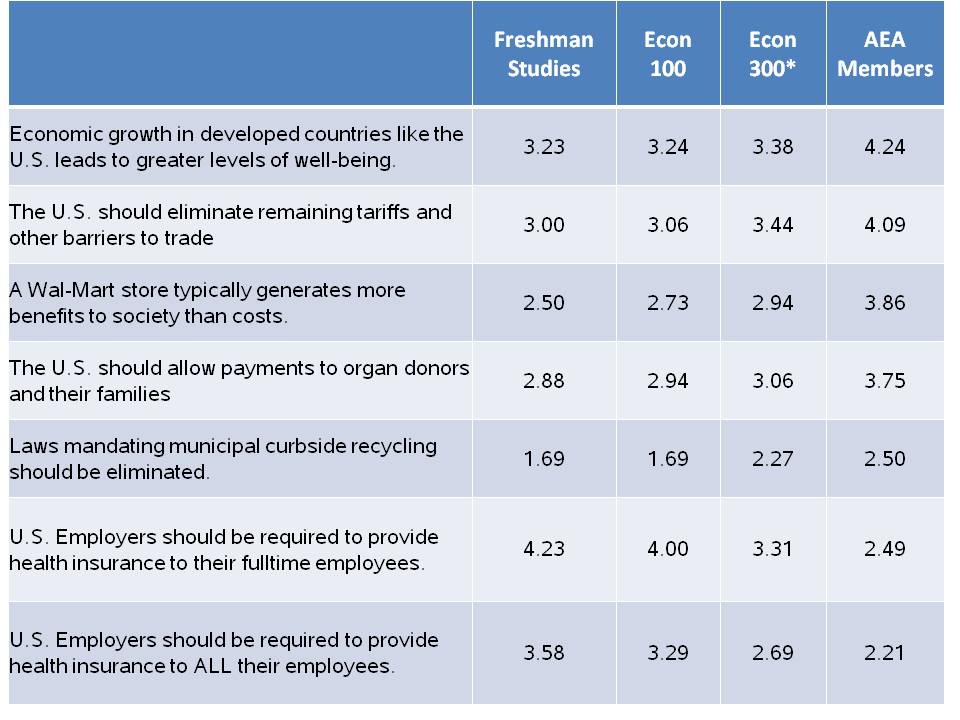

In the previous post, I mentioned the Robert Whaples survey of American Economic Association (AEA) members on their public policy views. Of course, Whaples isn’t the only one with access to Survey Monkey, and with the help of some of my colleagues, we gave the same survey to students in Freshman Studies, Economics 100, and Economics 300 courses.

The Freshman Studies sample (n=26) should be fairly representative of incoming freshman population, as every student takes freshman studies and these students are allegedly distributed randomly across the sections. I have data from two sections with a 90% response rate. The Econ 100 course is predominantly freshman as well, but is a much different cross section of the University, with 70% planning to major in economics or some other social science. The Econ 300 is, of course, generally for students taking the first “major” step to joining Team Econ down here on Briggs 2nd. It is well-worth noting that the Econ 100 (n=35) and Econ 300 students were surveyed at the beginning of the course,* not the end. Perhaps next year we will switch that up.

The survey participants rate the questions on a 1-5 scale, with 1 being strongly disagree and 5 being strongly agree.

Here are selected results, sorted by the scores of AEA members:

Continue reading Lawrence Students v. Card-Carrying Economists

The fashion industry, a $200 billion industry in the United States alone, is comprised of nearly 150,000 establishments, ranging in size from large fashion houses to smaller start-ups. Although there are a large number of firms competing in the industry, according to the 2002 Census, five percent of firms in the clothing industry accounted for twenty percent of total revenue and sales. These large firms, , also play an important role in the diffusion of new design trends and the continuation of induced obsolescence, the dynamic force driving the fashion cycle forward; the influence of large firms contributes to the top-down structure of the industry.

The fashion industry, a $200 billion industry in the United States alone, is comprised of nearly 150,000 establishments, ranging in size from large fashion houses to smaller start-ups. Although there are a large number of firms competing in the industry, according to the 2002 Census, five percent of firms in the clothing industry accounted for twenty percent of total revenue and sales. These large firms, , also play an important role in the diffusion of new design trends and the continuation of induced obsolescence, the dynamic force driving the fashion cycle forward; the influence of large firms contributes to the top-down structure of the industry. What would you do, indeed?

What would you do, indeed?