And the winner of the award for the most ridiculous angle of the LeBron James media feeding frenzy goes to The Atlantic for this gem:

How LeBron’s Move Helps the Tea Party

Excellent! I like it.

That’s all for now.

And the winner of the award for the most ridiculous angle of the LeBron James media feeding frenzy goes to The Atlantic for this gem:

How LeBron’s Move Helps the Tea Party

Excellent! I like it.

That’s all for now.

The Intrepid Professor Finkler has secured the Cinema in the Warch Campus Center to watch today’s US footballers take an Africa’s final hope, Ghana. The winner will move on to play Uruguay.

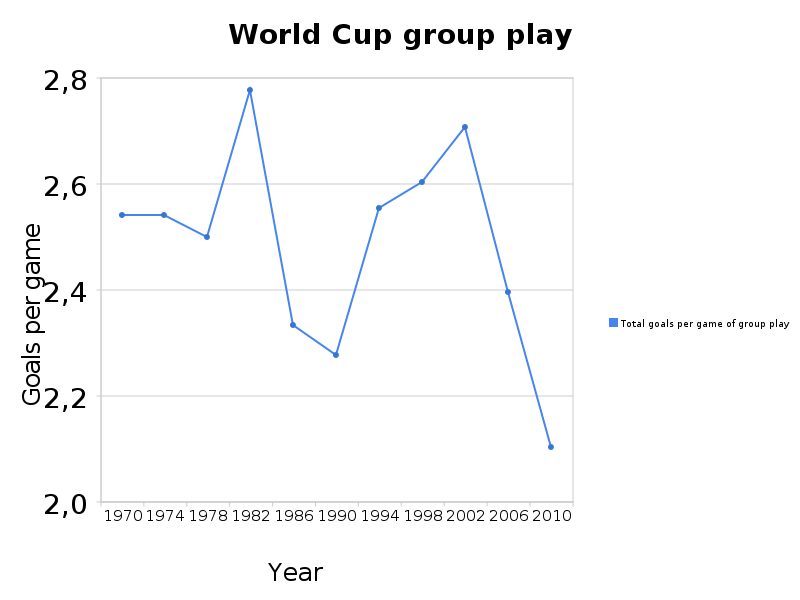

I have been puzzled as to why this year’s World Cup has had such a somnambulous effect on me. Is it the heavy prescription narcotics? Is it the gentle buzz of the vuvuzlas? Or perhaps it’s that the teams just aren’t putting the ball in the net?

It does seem that goals this year are even tougher to come by than usual, though that does not (necessarily) mean the games are more boring. It might mean tighter games down the stretch and even more exultation when the ball does go in the net.

Whatever the reason, we hope to see you in the Cinema for popcorn and football and possibly an impromptu game theoretic discussion of goalie strategy versus a penalty kick.

It’s June again, and that means it’s time to figure out exactly who you are going to pick to win this year’s FIFSA World Cup. What’s that? You’re busy with finals? With packing up and leaving campus? With finding a job and shopping for Ramen noodles? Who has time to research the top teams?

Why, the investment banks, of course.

Why, the investment banks, of course.

According to the Financial Times, Danske Bank, JP Morgan, UBS, Evolution, Goldman Sachs, have all put their top personnel on the matter and made their predictions. Well, Goldman only picked the semi-finalists because, you know, they don’t want to take any unnecessary risks.

It looks like la Brasilia is the big favorite this year, with a JP Morgan giving a hat tip to the English.

How do they do it?, you ask. Here’s one case:

Danske are using six factors (income level, population size, football history and tradition, current form of national team, presence of ‘superstars,’ and home field advantage) to gauge the teams relative strength… Then they simulate the Cup schedule.

That’s right, linear regression. OLS. What can’t it do?

For those of you US football fans out there, the yanks are better than even odds to advance past the group play, and about 90:1 to win it all right now. Spain is actually the gambling favorite to win it all right now at 4:1, with the Brazilians just behind at 9:2.

The New Republic has a blog.

So, did Major League Baseball’s steroid craze lead to the decimation of the baseball record book? The argument is straight forward enough, with the help of performance-enhancing drugs, hitters got bigger and stronger and started knocking the tater out of the park with alarming frequency. The extra-ordinary seasons from the likes of Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, and Barry Bonds are the proof in the steroid pudding.

So, did Major League Baseball’s steroid craze lead to the decimation of the baseball record book? The argument is straight forward enough, with the help of performance-enhancing drugs, hitters got bigger and stronger and started knocking the tater out of the park with alarming frequency. The extra-ordinary seasons from the likes of Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, and Barry Bonds are the proof in the steroid pudding.

But Art De Vany at UC-Irvine says it just isn’t so, and he just published a paper in Economic Inquiry making his case. The paper is appropriately titled “Steroids and Home Runs,” and it has a very direct and confident abstract:

There has been no change in Major League Baseball home run hitting for 45 yr, in spite of the new records. Players hit with no more power now than before. Records are the result of chance variations in at bats, home runs per hit, and other factors. The clustering of records is implied by the intermittency of the law of home runs. Home runs follow a stable Paretian distribution with infinite variance. The shape and scale of the distribution have not changed over the years. The greatest home run hitters are as rare as great scientists, artists, or composers.

Ah, where would we be without the Paretian distribution? If you don’t feel like plowing through the paper, you can hear him chat with Russ Roberts at EconTalk.

De Vany is quite a character. In addition to his academic prowess, he is a former professional athlete and a bona fide fitness and diet guru. He looks pretty good for a 50-year old… and he’s 70.

This seems to need no explanation. I wonder if you could do the same analysis from the annual Lawrence faculty picture?

Smile Intensity in Photographs Predicts Longevity

Ernest Abel & Michael Kruger

Psychological Science, forthcoming

“Photographs were taken from the Baseball Register for 1952 (Spink, Rickart, & Abramovich, 1952). We restricted our analysis to players who debuted prior to 1950, and we included only photographs in which the player appeared to be looking at the viewer…Players with Duchenne smiles were half as likely to die in any year compared with nonsmilers, HR = 0.50, p = .006…In this model, smile intensity accounted for 35% of the explained variability in survival”

A lot of people have been stopping me in the halls asking, Is there any way we could somehow use a Markov-Chain model to help with March Madness tournament picks?

Well, folks, it’s your lucky day.

Paul Kvam and Joel Sokol out of Georgia Tech published a piece in Naval Research Logistics a few years back explaining a simple three-parameter model. (In the event that the Mudd doesn’t have an old copy laying around, you can read it here).

For those of you without time to crunch the numbers yourself, you might check out the handy LRMC Information Page. Last year I went with the “Pure” LRMC, but this year I’m feeling a little Bayesian.

The authors claim — and there appears to be something to their claim — that their model does a better job than the experts and competing methods (e.g., seeds, RPI, rankings). And here’s a shocker — they have Kansas over Duke in the final (like it took a genius to come up with that). On the other hand, they have BYU as their #4 team, so I will bet the farm on that one watch that game with interest.

The Olympics are upon us, and economists of many stripes are gathering to watch the figure skating, dish about the routines and outfits, and speculate which judges are corrupt. Fortunately, one of our own, Eric Zitzewitz of Dartmouth, has been gathering data to give us the low-down on the corruption problem. Ray Fisman discusses the research in a recent Slate piece.

The 2002 Winter Games in Salt Lake City were tainted by a figure skating scandal in which judges from five countries allegedly colluded to deliver victory to a Russian couple over a pair of Canadians…. [Economist Eric] Zitzewitz found that the “home judges bias” added nearly 0.2 points to skaters’ scores (on a six-point scale), often enough to boost their ranking by at least one position. [H]aving a countryman on the panel helped a skater not just through the direct effect of that one judge’s scoring–the home-country judge also convinced others on the panel to inflate their scores.

What was the solution? Well, perhaps paradoxically, it was to make judges anonymous and set up the classic prisoners dilemma situation. In other words, if we agree to give each other’s skaters inflated scores, then I need to be able to observe what score you give to ensure that you are keeping up your end of the bargain. Absent that, your strategy should be to “defect” from our agreement because your skater certainly benefits from the rival’s lower score.

Was that the effect? In a word: No.

The home-country bias gets even worse when anonymous judges can hide from a scrutinizing press and public, despite the barriers that anonymity may create for effective backroom deal-making. The home-judge advantage under the new system is about 20 percent higher than in the days of full disclosure. (Zitzewitz can’t say how much of this increase in bias is from the home-country judge himself, and how much from others he’s persuaded to go along with him; how each judge has scored a performance–and which judges’ scores are counted–are kept secret.)

Fascinating either way. Perhaps they should find figure skating judges from countries that don’t have any serious figure skaters?