A $1 million bequest from an anonymous donor will provide valuable research support for Lawrence University faculty while honoring the college’s 14th president, and his wife, Lawrence officials have announced.

The bequest establishes the Richard and Margot Warch Fund for Scholarly Research. The fund will be administered by Provost and Dean of the Faculty David Burrows for faculty scholarship, travel expenses, student research support and the purchase of research materials, including instrumentation and books.

“One of the great strengths of a Lawrence education is the opportunity for students to work closely with faculty who are engaged in scholarly or creative projects,” said Burrows. “Our faculty are outstanding scholars and creative artists as well as excellent teachers. These funds will enhance the support available to faculty. All faculty will be eligible to apply for small grants that will help them complete such projects.”

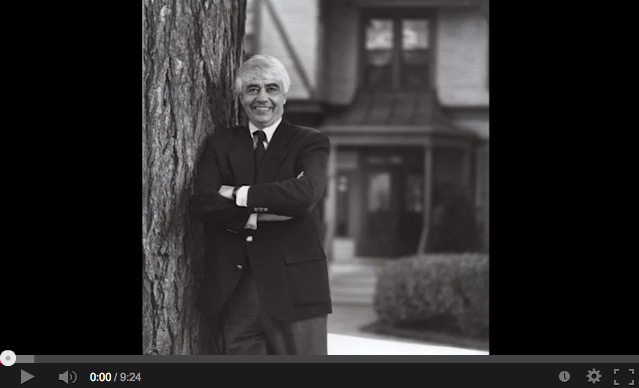

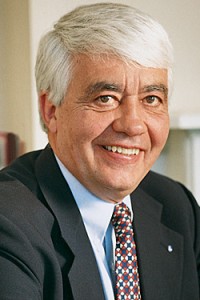

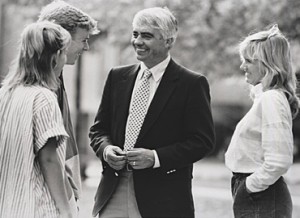

The endowed fund honors Richard “Rik” Warch, former dean of the faculty and the second-longest serving president in Lawrence history, who led the college from 1979-2004, and his wife, Margot. President Warch passed away in September, 2013 at the age of 74.

“Rik felt interactions between faculty and students were the essence of the Lawrence experience,” said Margot Warch. “He celebrated the work and achievements of each faculty member as dean of the faculty and as president was always looking for dollars to encourage scholarship and development projects. He would be thrilled to know that a fund bearing our names now exists to support faculty research.”

Funds to support faculty research will become available beginning with the 2014-15 academic year.

About Lawrence University

Founded in 1847, Lawrence University uniquely integrates a college of liberal arts and sciences with a nationally recognized conservatory of music, both devoted exclusively to undergraduate education. It was selected for inclusion in the Fiske Guide to Colleges 2014 and the book “Colleges That Change Lives: 40 Schools That Will Change the Way You Think About College.” Individualized learning, the development of multiple interests and community engagement are central to the Lawrence experience. Lawrence draws its 1,500 students from nearly every state and more than 50 countries.