For those of you grousing about looking for the whens and wheres of the Lawrence Scholars in Business Entertainment Summit, you’ve come to the right place. It is today at 4 p.m. in the Hurvis Room of the Warch Campus Center. Dinner to follow at 6, space permitting.

This is the final LSB event of the year, and should appeal to folks of all stripes, from the economics majors to the Conservatory and Arts students.

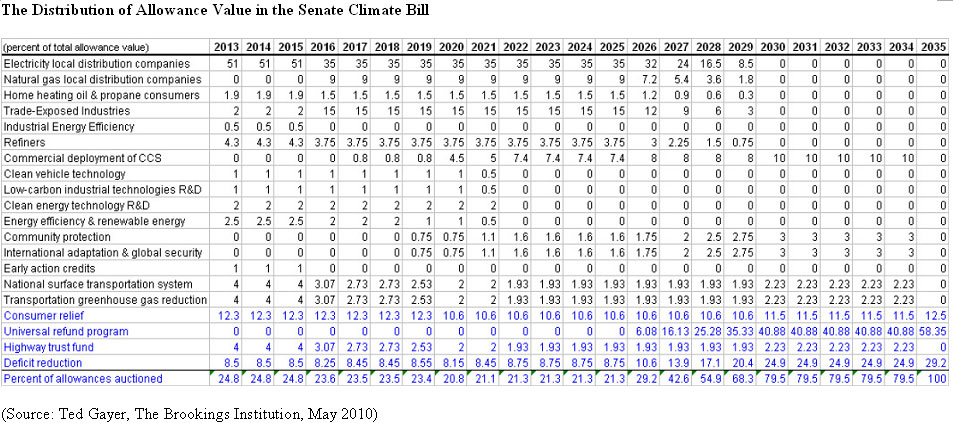

Click the poster for the full report.

The second book is The Marketplace of Ideas: Reform and Reaction in the American University by Louis Menand. This is a provocative piece about why although academics tend to be liberal as a bunch, but institutional change within the academy is slow going.

The second book is The Marketplace of Ideas: Reform and Reaction in the American University by Louis Menand. This is a provocative piece about why although academics tend to be liberal as a bunch, but institutional change within the academy is slow going. The

The

… is certainly worth a barrel of cure. Instead of having these guys with big yellow boots (I thought only 4-year old boys ran around in public in galoshes out of season), perhaps it would pay to have more egghead types crunching data on safety risk. That was the message I gave in both my classes this week, as we sat down to read Shultz and Fischbeck’s “

… is certainly worth a barrel of cure. Instead of having these guys with big yellow boots (I thought only 4-year old boys ran around in public in galoshes out of season), perhaps it would pay to have more egghead types crunching data on safety risk. That was the message I gave in both my classes this week, as we sat down to read Shultz and Fischbeck’s “

Just don’t try to sell the kits at Walgreens.

Just don’t try to sell the kits at Walgreens. On the other side of the pond, there actually is a cap & trade system in place, and it is really all over the price. Carbon prices have ranged from €8 to €30, and the volatility can stymie long-term investments. In other words, there is likely to be an inverse relationship between carbon prices and the payoff to greener (or at least lower-carbon) energy sources. If investors don’t believe that carbon prices will be high, then green investments simply won’t be as attractive.

On the other side of the pond, there actually is a cap & trade system in place, and it is really all over the price. Carbon prices have ranged from €8 to €30, and the volatility can stymie long-term investments. In other words, there is likely to be an inverse relationship between carbon prices and the payoff to greener (or at least lower-carbon) energy sources. If investors don’t believe that carbon prices will be high, then green investments simply won’t be as attractive. There seems to be some difference in the moment-to-moment intensity of an auction theory class and that of an actual auction. Especially when the S&P is amidst an epic tank.

There seems to be some difference in the moment-to-moment intensity of an auction theory class and that of an actual auction. Especially when the S&P is amidst an epic tank. A few weeks ago, despite its substantial girth, I added the new Kaufmann Foundation volume, Invention of Enterprise: Entrepreneurship from Ancient Mesopotamia to Modern Times to the black hole that is my reading list. The reason for my excitement was the extra-ordinary group of volume editors. David Landes is a pioneer in entrepreneurship and development, having written the highly-regarded

A few weeks ago, despite its substantial girth, I added the new Kaufmann Foundation volume, Invention of Enterprise: Entrepreneurship from Ancient Mesopotamia to Modern Times to the black hole that is my reading list. The reason for my excitement was the extra-ordinary group of volume editors. David Landes is a pioneer in entrepreneurship and development, having written the highly-regarded  Many theories, most famously Max Weber’s essay on the ‘Protestant ethic,’ have hypothesized that Protestantism should have favored economic development. With their considerable religious heterogeneity and stability of denominational affiliations until the 19th century, the German Lands of the Holy Roman Empire present an ideal testing ground for this hypothesis. Using population figures in a dataset comprising 276 cities in the years 1300-1900, I find no effects of Protestantism on economic growth. The finding is robust to the inclusion of a variety of controls, and does not appear to depend on data selection or small sample size. In addition, Protestantism has no effect when interacted with other likely determinants of economic development. I also analyze the endogeneity of religious choice; instrumental variables estimates of the effects of Protestantism are similar to the OLS results.

Many theories, most famously Max Weber’s essay on the ‘Protestant ethic,’ have hypothesized that Protestantism should have favored economic development. With their considerable religious heterogeneity and stability of denominational affiliations until the 19th century, the German Lands of the Holy Roman Empire present an ideal testing ground for this hypothesis. Using population figures in a dataset comprising 276 cities in the years 1300-1900, I find no effects of Protestantism on economic growth. The finding is robust to the inclusion of a variety of controls, and does not appear to depend on data selection or small sample size. In addition, Protestantism has no effect when interacted with other likely determinants of economic development. I also analyze the endogeneity of religious choice; instrumental variables estimates of the effects of Protestantism are similar to the OLS results. That’s the answer. The question is from

That’s the answer. The question is from  So that gets us back to the original question, which is, should we think about the regulatory framework for the current oil spill fiasco in terms of regulating some sort of risk or internalizing an externality? And, does it make a difference which approach we take in terms of the types of regulations we would want?

So that gets us back to the original question, which is, should we think about the regulatory framework for the current oil spill fiasco in terms of regulating some sort of risk or internalizing an externality? And, does it make a difference which approach we take in terms of the types of regulations we would want?