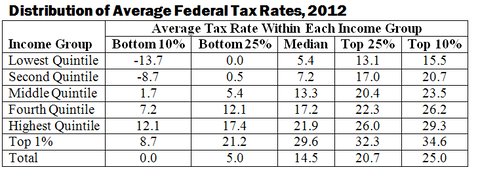

In today’s Economix blog, Bruce Bartlett argues that our Federal income tax burden violates two fundamental economic principles. Although the tax system on average is progressive (in the sense that households in higher income groups pay on average proportionately higher tax rates than those in lower income groups), it violates both horizontal and vertical equity. Horizontal equity requires that people with the same income and circumstances should pay the same tax rate. Vertical equity usually is interpreted to mean that those with greater ability to pay (higher income and all else equal) should pay higher tax rates. As the chart below, taken by Bartlett from the Annual Report of the Council of Economic Advisors Report for 2012, shows numerous inequities exist.

The chart should be read horizontally. For those in the middle quintile (40-60% levels) of income, the average income tax rate ranges from 1.7% to 23.5%. For those in the top 1% bracket, the range is from 8.7% to 34.6%. Clearly horizontal inequity exists within each quintile and vertical inequity exists across quintiles, since many in higher quintiles pay a lower rate than many in lower quartiles.

These results arise because different incomes are taxed differently. Those whose incomes are attributed to labor face higher rates than those whose income can be attributed to capital. This is especially pertinent for investment fund managers who are paid in capital gains rather than salary. Not only do they pay a lower income tax rate than those with the same level of income but they also avoid some payroll taxes assessed against wages and salary income.

Any serious attempt at tax reform should directly confront these inequities not only for “fairness” reasons but because the income tax system provides strong incentives that distort the allocation of labor and human capital toward favored categories, many of which benefited greatly over the past decade.