The “Ec 10 Walkout” at Harvard has garnered some media attention—Ec 10 being the famous introductory economics course at Harvard, “taught” by Gregory Mankiw. Only about 10% of his class walked out, which comes out to be about 70 students. (Yes, that means that the intro econ lectures at Harvard have 700 students, and they see Mankiw about 5 times and from far away.) The revolution was, in fact, televised. When I was in 7th grade, we did something similar in math class, but nobody paid much attention. Probably because we didn’t have youtube.

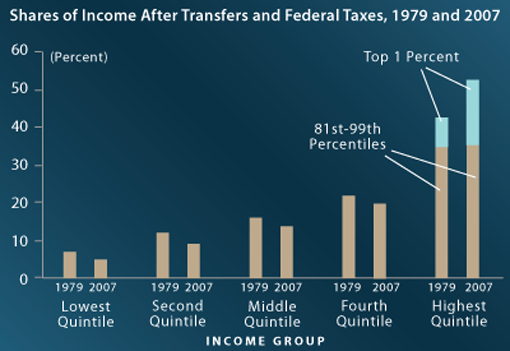

NPR managed to find a freshman who went on the record with this statement: “I’m someone who lives below the poverty line, my family’s extremely poor. And having a class like this that promotes gaining at the expense of millions of people disturbs me and bothers me at my core.” A few more students made similar statements: “Their specific criticisms are that economics as taught in this class, formally called Economics 10, failed to prevent the financial crisis and does nothing to narrow the gap between rich and poor.” Read more. These quotes confirm that even at Harvard, one can apparently find students who are clueless about economics yet feel that they are in a strong position to criticize it. Mankiw’s blog has a post on the event, including the students’ open letter, and another post on the NPR interview with Mankiw on the subject. Finally, take a look at this defense of Ec 10 from a student.