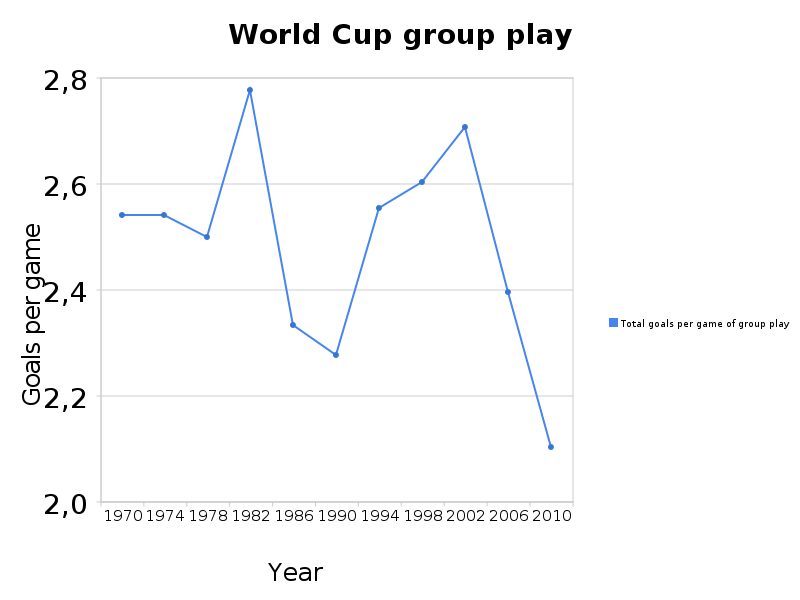

Almost unnoticed, this week marks a terrible week for advocates of market solutions to environmental problems, including various cap-and-trade systems. The Wall Street Journal reports that new federal air pollution rules have resulted in the tanking of the sulfur dioxide market, rendering extant permits worthless.

Almost unnoticed, this week marks a terrible week for advocates of market solutions to environmental problems, including various cap-and-trade systems. The Wall Street Journal reports that new federal air pollution rules have resulted in the tanking of the sulfur dioxide market, rendering extant permits worthless.

Often referred to as “the grand policy experiment,” (also here), the SO2 market was considered a success, and thought of as a model for potential global system to reduce greenhouse gases. As with so many cases in economics, a credible commitment matters. The Journal sums it up nicely:

The market’s collapse shows how vulnerable market-based approaches to reducing air pollution are to government actions. That could scare off investors, who won’t commit to a market where the rules can change at any minute.

Indeed.

One of the great benefits of using market instruments to address environmental problems is that they can substantial lower the costs. The law of demand says that as price goes up, people buy less. As a result of the collapses of this market, we will likely pay more to get less in terms of environmental quality. This may well undermine efforts to implement market solutions elsewhere. If investors are convinced the regulatory environment is unstable or uncertain, they are unlikely to make large capital investments, and are more likely to take stopgap measures.

Speaking of careers in business,

Speaking of careers in business,  I saw an interesting bit over at Bloomberg Businessweek about how to think about the trajectory. It’s colorful, gangsta-esque title is “Krugman or Paulson: Who You Gonna Bet On?” On the one hand, you have Paul Krugman warning of a depression

I saw an interesting bit over at Bloomberg Businessweek about how to think about the trajectory. It’s colorful, gangsta-esque title is “Krugman or Paulson: Who You Gonna Bet On?” On the one hand, you have Paul Krugman warning of a depression  “The safer they make the cars, the more risks the driver is willing to take. It’s called the Peltzman effect.” — Some CSI Episode

“The safer they make the cars, the more risks the driver is willing to take. It’s called the Peltzman effect.” — Some CSI Episode For today’s recommended reading, The New York Times

For today’s recommended reading, The New York Times

As a trained economist, I know the basic institutional details and understand the basic arguments, but as Barro suggests, I have no great insight on the empirics or which side of the debate is likely to be correct.

As a trained economist, I know the basic institutional details and understand the basic arguments, but as Barro suggests, I have no great insight on the empirics or which side of the debate is likely to be correct.

Here are a few links for you as we bid farewell to the 2010 Lawrence economics graduates and brace ourselves for the alumni revelers descending upon campus for Reunion Weekend. As Neil Young might say, economics never sleeps.*

Here are a few links for you as we bid farewell to the 2010 Lawrence economics graduates and brace ourselves for the alumni revelers descending upon campus for Reunion Weekend. As Neil Young might say, economics never sleeps.* On a happier innovation front, the most recent EconTalk

On a happier innovation front, the most recent EconTalk

Why, the investment banks, of course.

Why, the investment banks, of course.