I was having a discussion with one of my colleagues about Chinese economic growth prospects, and I invoked this Nouriel Roubini (a.k.a., Dr. Doom) piece, “China’s Bad Growth Bet.” The basic argument is that China is overcapitalized and this will lead to problems:

China has grown for the last few decades on the back of export-led industrialization and a weak currency, which have resulted in high corporate and household savings rates and reliance on net exports and fixed investment (infrastructure, real estate, and industrial capacity for import-competing and export sectors). When net exports collapsed in 2008-2009 from 11% of GDP to 5%, China’s leader reacted by further increasing the fixed-investment share of GDP from 42% to 47%.

Thus, China did not suffer a severe recession – as occurred in Japan, Germany, and elsewhere in emerging Asia in 2009 – only because fixed investment exploded. And the fixed-investment share of GDP has increased further in 2010-2011, to almost 50%.

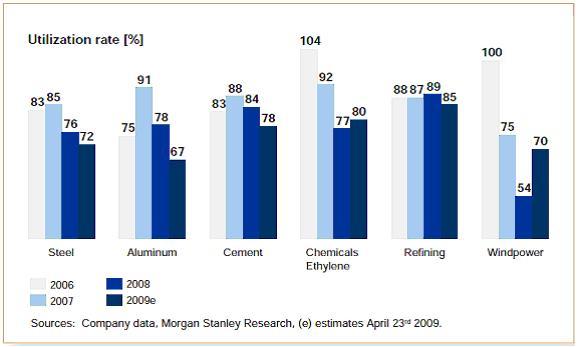

The problem, of course, is that no country can be productive enough to reinvest 50% of GDP in new capital stock without eventually facing immense overcapacity and a staggering non-performing loan problem. China is rife with overinvestment in physical capital, infrastructure, and property. To a visitor, this is evident in sleek but empty airports and bullet trains (which will reduce the need for the 45 planned airports), highways to nowhere, thousands of colossal new central and provincial government buildings, ghost towns, and brand-new aluminum smelters kept closed to prevent global prices from plunging.

With reunion upon us, it is an excellent time to ask, “why go to college?” Indeed. To help us out with that question, Louis Menand has a provocative piece in a recent

With reunion upon us, it is an excellent time to ask, “why go to college?” Indeed. To help us out with that question, Louis Menand has a provocative piece in a recent

Now that Commencement has passed, we can get on with our summers. For me, that means I can try to take a bite out of the big, tasty stack of books I have been accumulating over the past 9 months.

Now that Commencement has passed, we can get on with our summers. For me, that means I can try to take a bite out of the big, tasty stack of books I have been accumulating over the past 9 months.

This fall, Professor Galambos and I will be leading a group read of F.A. Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom. The course will be offered for one unit as DS 391 — On the Road with Hayek, and we will have a sign up and coordinate times at the beginning of fall term. I expect with this book we will probably meet eight of the ten weeks.

This fall, Professor Galambos and I will be leading a group read of F.A. Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom. The course will be offered for one unit as DS 391 — On the Road with Hayek, and we will have a sign up and coordinate times at the beginning of fall term. I expect with this book we will probably meet eight of the ten weeks.