The Intrepid Professor Finkler has secured the Cinema in the Warch Campus Center to watch today’s US footballers take an Africa’s final hope, Ghana. The winner will move on to play Uruguay.

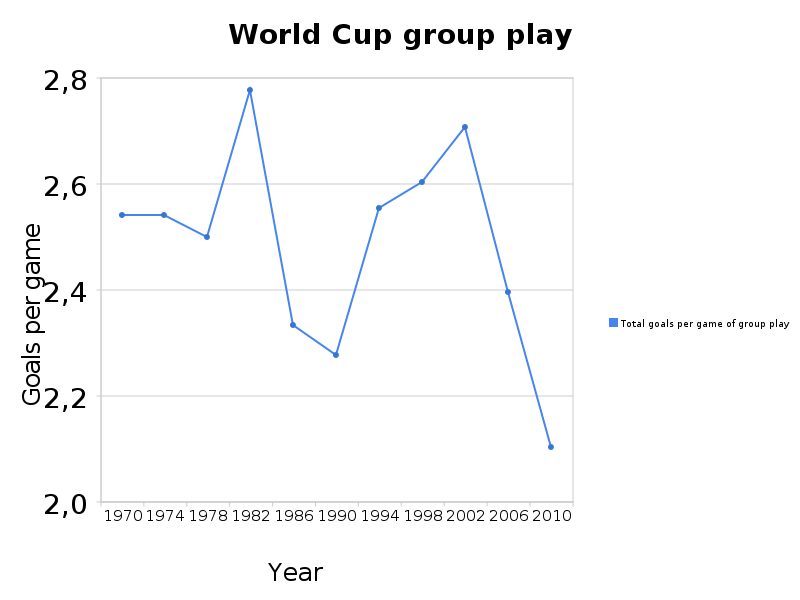

I have been puzzled as to why this year’s World Cup has had such a somnambulous effect on me. Is it the heavy prescription narcotics? Is it the gentle buzz of the vuvuzlas? Or perhaps it’s that the teams just aren’t putting the ball in the net?

It does seem that goals this year are even tougher to come by than usual, though that does not (necessarily) mean the games are more boring. It might mean tighter games down the stretch and even more exultation when the ball does go in the net.

Whatever the reason, we hope to see you in the Cinema for popcorn and football and possibly an impromptu game theoretic discussion of goalie strategy versus a penalty kick.

Here are a few links for you as we bid farewell to the 2010 Lawrence economics graduates and brace ourselves for the alumni revelers descending upon campus for Reunion Weekend. As Neil Young might say, economics never sleeps.*

Here are a few links for you as we bid farewell to the 2010 Lawrence economics graduates and brace ourselves for the alumni revelers descending upon campus for Reunion Weekend. As Neil Young might say, economics never sleeps.* On a happier innovation front, the most recent EconTalk

On a happier innovation front, the most recent EconTalk

Why, the investment banks, of course.

Why, the investment banks, of course. When you have the money–and “you” are a big, economically and culturally vital nation–you get more than just a higher standard of living for your citizens. You get power and influence, and a much-enhanced ability to act out. When the money drains out, you can maintain the edge in living standards of your citizens for a considerable time (as long as others are willing to hold your growing debts and pile interest payments on top). But you lose power, especially the power to ignore others, quite quickly–though, hopefully, in quiet, nonconfrontational ways. An you lose influence–the ability to have your wishes, ideas, and folkways willingly accepted, eagerly copied, and absorbed into daily life by others. As with good parenting, you hope that by the time this happens those ideas and ways have been so thoroughly integrated that they have become part of what is normal and regular abroad as well as at home; sometimes, of course, they don’t. In either case, the end is inevitable: you must become, recognize that you have become, and act like a normal country. For America, this will be a shock: American has not been a normal country for a long, long time.

When you have the money–and “you” are a big, economically and culturally vital nation–you get more than just a higher standard of living for your citizens. You get power and influence, and a much-enhanced ability to act out. When the money drains out, you can maintain the edge in living standards of your citizens for a considerable time (as long as others are willing to hold your growing debts and pile interest payments on top). But you lose power, especially the power to ignore others, quite quickly–though, hopefully, in quiet, nonconfrontational ways. An you lose influence–the ability to have your wishes, ideas, and folkways willingly accepted, eagerly copied, and absorbed into daily life by others. As with good parenting, you hope that by the time this happens those ideas and ways have been so thoroughly integrated that they have become part of what is normal and regular abroad as well as at home; sometimes, of course, they don’t. In either case, the end is inevitable: you must become, recognize that you have become, and act like a normal country. For America, this will be a shock: American has not been a normal country for a long, long time.

BP’s stock, which traded at a 52-week high of $62.38 on Jan. 19, 2010, closed on June 1 at $36.52 a share, down 15% on the day. The post-spill sell-off has wiped out some $68 billion of BP’s market value, knocking it down to $114 billion. With the stock now in the cellar, some speculation even has it that BP may attract a buyer.

BP’s stock, which traded at a 52-week high of $62.38 on Jan. 19, 2010, closed on June 1 at $36.52 a share, down 15% on the day. The post-spill sell-off has wiped out some $68 billion of BP’s market value, knocking it down to $114 billion. With the stock now in the cellar, some speculation even has it that BP may attract a buyer. He finds big impacts. The red line in the picture is his estimate of the time series of BP’s stock price without the spill, and the black line is the actual price. Seems like a big effect.

He finds big impacts. The red line in the picture is his estimate of the time series of BP’s stock price without the spill, and the black line is the actual price. Seems like a big effect.