Why Local Water Rates Matter and What We Can Do About It

Thomas Chesnutt A&N Technical Services Monday at 4:30 p.m. Steitz Hall 102.

Why Local Water Rates Matter and What We Can Do About It

Thomas Chesnutt A&N Technical Services Monday at 4:30 p.m. Steitz Hall 102.

I will be showing the PBS Series, Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water, Wednesday and Thursday night in Briggs 223. The episodes will go off on the hour each night. Episode summaries are here.

The documentary series is based on Marc Reisner’s epic novel about western water development, and particularly the role of the Bureau of Reclamation and the Army Corps of Engineers in shaping that destiny (NYT review here). The first episode is about the delivery of water to Los Angeles and how that shaped the development of that urban area. The second focuses specifically on the Colorado River and how that is divvied up. The third episode looks at agricultural development in California’s Central Valley.

9 p.m. Mullholland’s Dream

10 p.m. An American Nile

11 p.m. The Mercy of Nature

For you homebodies, the YouTube playlist is here.

We will host an Economics Tea on Monday, April 21 at 4:30 in Briggs 217 to convene for lively discussion and delicious pie. Faculty will be available to discuss pre-registration and give advice to anyone interested in learning more about the department major. We will once again be offering various types of pie.

For the Google-impaired amongst you, here is a link to the major and minor requirements.

Key things for potential majors to know:

The core series sequence is Micro Theory (ECON 300), Econometrics (ECON 380), and Macro Theory (ECON 320). These are generally offered once per year, with ECON 300 in the fall, ECON 380 in the winter, and ECON 320 in the spring. We believe that taking these back-to-back-to-back is a good strategy.

You need calculus (MATH 140 OR MATH 120 & MATH 130) in order to take Econ 300.

You need calculus in order to take Introduction to Probability and Statistics (MATH 207). Math 207 is only offered in the fall term each year.

You need MATH 207 and either ECON 300 or ECON 320 in order to take Econometrics (ECON 380). We recommend that you take MATH 207 in the fall and ECON 380 in the winter.

The full schedule is right here.

We hope you will take advantage of the opportunities to explore your options for life after Lawrence by attending the Career Conference on Saturday, April 5.

Alumni representing the classes of ‘07, ‘02, ‘84, ‘82 and ’76 will discuss how YOUR liberal arts education can differentiate you in today’s competitive marketplace. Hear tips for success from: Director of Consumer Research and Insights, an Owner, an Entrepreneur and Early-stage Investor/CEO and CTO, Consulting Analyst and a Senior VP of Technology & Innovation. Plan to attend the events to build your network of people willing and able to help you navigate the business world!

Need internship funding? Stop by the Fellowships, Major Scholarships and Grants Resources Fair, 11 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. in WCC.

Contact careerservices@lawrence.edu for more information/registration.

Remarkably, this is the 1000th post on the Lawrence Economics Blog. Wow.

Along the way, we have demonstrated that economists are in surprising agreement about a surprising number of things, though we tend to differ from Lawrence students. We have had some actual economic analysis, such as explaining Giffen Goods to Matthew Yglesias, evaluating the argument that a great wine shortage is upon us, and reviewing Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers.

We’ve also looked at topics such as consumption smoothing (for goods such as underwear) without and with a random stopping point (such as a robot uprising).

I’d probably be remiss if I didn’t mention something about innovation, such as our (okay, my) continuing fascination with Joseph Schumpeter, as well as these remarkable spitballing roots of an American icon.

He’s a doctor, he’s a college professor, but he’s also a sort of rough and tumble guy.

Spanning the globe, we have taken on the literal meaning of place names, challenged the conventional wisdom on why people (such as Jonathan) vote the way they do, and normalized the data for Olympic medal counts so that Hungary might fare a little better.

Speaking of Hungary and the eastern block, Professor Galambos’ has posted some great stuff on Goulash Capitalism and his (should-be) annual Lenin’s birthday message.

No doubt our most intriguing posts are our continuing series on moral (and other) hazards. Here’s a taste:

L.W. Burdeshaw, an insurance agent in Chipley, told the St. Petersburg Times in 1982 that his list of policyholders included the following: a man who sawed off his left hand at work, a man who shot off his foot while protecting chickens, a man who lost his hand while trying to shoot a hawk, a man who somehow lost two limbs in an accident involving a rifle and a tractor, and a man who bought a policy and then, less than 12 hours later, shot off his foot while aiming at a squirrel.

“There was another man who took out insurance with 28 or 38 companies,” said Murray Armstrong, an insurance official for Liberty National. “He was a farmer and ordinarily drove around the farm in his stick shift pickup. This day – the day of the accident – he drove his wife’s automatic transmission car and he lost his left foot. If he’d been driving his pickup, he’d have had to use that foot for the clutch. He also had a tourniquet in his pocket. We asked why he had it and he said, ‘Snakes. In case of snake bite.’ He’d taken out so much insurance he was paying premiums that cost more than his income. He wasn’t poor, either. Middle class. He collected more than $1-million from all the companies. It was hard to make a jury believe a man would shoot off his foot.”

Who knew people were so crazy, er, rational? Anyway, Incentives matter!

There is a recent NYT piece on the proposed iron mine project up on the Bad River in northern Wisconsin, and it is a big mine indeed:

The $1.5 billion mine would initially be close to four miles long, up to a half-mile wide and nearly 1,000 feet deep, but it could be extended as long as 21 miles. In its footprint lie the headwaters of the Bad River, which flows into Lake Superior, the largest freshwater lake in the world and by far the cleanest of the Great Lakes. Six miles downstream from the site is the reservation of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, whose livelihood is threatened by the mine.

The piece cites our own geologist, Marcia Bjorenrud, who evidently investigated the possibility of acid drainage from the project:

Before the passage of the bill, Marcia Bjornerud, a geology professor at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wis., testified before the legislature that samples she had taken from the mine site revealed the presence of sulfides both in the target iron formation and in the overlying rock that would have to be removed to get to the iron-bearing rocks. (When exposed to air and water, sulfides oxidize and turn water acidic, which can be devastating to rivers and streams, along with their fish populations.) Sulfide minerals, Professor Bjornerud said, would be an unavoidable byproduct of the iron mining. But the bill does not mandate a process for preventing the harm from the sulfide minerals that mining would unleash.

Acid drainage is a particularly nasty problem associated with many mining projects, so these issues tend to be at the fore of any mine permitting process. When sulfides are exposed to water and air, they oxidize and become acidic. The overhead shots from problem mines often look like someone dumped battery acid into a sink (see here from this photo essay of a particularly egregious case).

Thnx to “Mr. E” for the pointer.

Over the next few weeks, we will be compiling some resources for those of you who are interested in doing graduate work in economics. Certainly, your first stop should be to talk with one or more of your professors (especially the economics professors, I suppose). The American Economic Association is probably your next stop.

Over the next few weeks, we will be compiling some resources for those of you who are interested in doing graduate work in economics. Certainly, your first stop should be to talk with one or more of your professors (especially the economics professors, I suppose). The American Economic Association is probably your next stop.

You might also check out the Miles Kimball / Noah Smith essay on the economics Ph.D.

I have this on my mind because I just received Stuart Hillmon’s Getting a Ph.D. in Economics in the mail. If you care to take a look at the book, you can come by and I’ll loan it to you.

Tyler Cowen comments.

2 or 3 Units. Professor Gerard

Prerequisites: ECON 400 or 450, ECON 380, Junior or Senior Standing, and Permission of Instructor

This reading group is a continuation of Economics 450, intended for students with a continuing interest in organizational economics. Click for the provisional reading list: Continue reading 391 DS – Readings in Organizational Economics

If you’ve ever wondered what an “S-Curve” is in the context of the diffusion of innovations, check out the piece at Quartz on “The Slow Death of the Microwave.” The piece shows what are effectively household adoption rates of various consumer items over the past 100+ years. It is called an “S” curve because the initial roll out tends to be somewhat prolonged (the bottom _ of the S) followed by a rather steep increase as the item catches on (the / part), and finally a leveling off when most of the population has adopted it. The curves themselves contrast both rates of diffusion and total penetration rates. The microwave, for example, went from 10 to 80% of households in a ten-year period. Compare that with stoves, washers, dryers, and even telephones, which took their sweet time becoming the proverbial “household” items.

The figure* actually says a lot about the characteristics of American households. At the onset of World War II, for instance, the majority of households did not have refrigerators, clothes washers, telephones, or color televisions. The curves also show the dramatic impact of the Great Depression on the diffusion of telephones, electricity (both stunting then accelerating diffusion), and automobiles.

As for the article, it’s a fascinating look at the microwave, though it seems a bit premature to be calling its “death,” given that the vast majority of households can still pop corn and defrost meat in short order. Bloomberg seems to agree with me on this point.

But when you read a little deeper, it turns out that people aren’t actually abandoning microwaves; they’re just not replacing them as frequently.

Yep. Still some cool graphics, though.

Here are some courses, updates, etc… germane to the Spring term on Briggs 2nd:

(NEW) ECON 495: Mathematics for Economists ARRANGED Professor Rhodes. This course is a 400-level course emphasizing some of the fundamental mathematical theory and practice common in the economics profession. We are in the process of coordinating times and places, so please contact Professor Rhodes or Gerard ASAP is you are interested.

ECON 495: Individual and Community TR 12:30-2:20 in the Econ Seminar Room, Professor Wulf.

Professor Steve Wulf (!) is cross-listing his fabulous course for the economics department for the first time. That being the case, here is the course description: This course studies a variety of theoretical responses to the emergence of open societies in the West. Topics include the competing demands of individuality and community in religious, commercial, and political life. The course promises a very healthy dose of history of economic thought.

ECON 460: International Trade MWF 8:30-9:40 in the Econ Seminar Room, Professor Devkota.

ECON 405: Innovation and Entrepreneurship 9:50-11:00 MWF in the Econ Seminar Room, Professor Galambos.

For those of you looking for some theoretical foundations to thinking about innovation & entrepreneurship, look no farther. An excellent complement to IO and Theory of the Firm.

ECON 320: Intermediate Macroeconomics MTWR Briggs 223.

Always a highlight!

CANCELLED ECON 295: Labor Economics 3:10-4:20 MWF in the Econ Seminar Room, Professor Rhodes

ECON 200: Development Economics 11:10-12:20 MWF in the Econ Seminar Room, Professor Devkota

This is also a good bet for next term, especially for those interested in understanding economic growth across countries.

ECON 225: Decision Theory MWF 1:50-3:00 Briggs 223, Professor Galambos

This class is not full, but enrollment is heavy (30+). We have committed to offering this in 2014-15 and expect it will be offered in 2015-16.

ECON 280: Environmental Economics TR 12:30-2:20, Briggs 223, Professor Gerard

This class is full and the current wait list is at about 8 or 9. It is offered each year, including Spring 2015.

ECON 120: Introduction to Macroeconomics MWF 12:30-1:40, Briggs 223, Professor Rhodes

The longest journey begins with the first step… and then the second step. This could go either way, as ECON 100 is not a prerequisite.

As I gear up for (count ’em) two environmental studies courses next term, I turn to Mother Jones for inspiration. And she delivers an extraordinary feature article on the environmental and energy implications of marijuana production. I can’t speak to the merits or accuracy of the article’s contentions, but I was struck by this bewildering assertion:

My guess is that, like most crop farming, marijuana cultivation would use a lot less energy per unit output if it was grown at scale. Indeed, it’s kind of hard to imagine that any indoor growing would be efficient at $0.15 kWh.

Even so, nine percent of electricity use seems incredibly high.

Back in 2003, the combination of heat and bad air quality in Paris got so bad that it claimed the lives of an estimated 10,000 people.

That was one nasty wave of heat and pollution.

It seems that something other than love is in the air once again, and things have gotten so bad that Paris officials banned all cars with even numbered license plates this past Monday. The reason is the shockingly high levels of particulate matter concentration (PM). PM is a “criteria” pollutant regulated by the EPA, and it is linked to possibly several hundred thousand premature deaths each year. In the US, however, the dominant source of emissions is coal-fired power plants, whereas the EU has a much bigger share of its passenger vehicles powered by diesel fuel. These diesel vehicles are much greater contributor to PM than the gasoline-powered vehicles common in the US.

From the AP story:

The safe limit for PM10 is set at 80 microgrammes per cubic metre (mcg/m3). At its peak last week, Paris hit a high of 180 mcg/m3 but this had fallen to 75 mcg/m3 by Monday.

I suppose the fact that it fell to 75 mcg/m3 is comforting, but that is still very high. As a basis for comparison, I picked a monitoring station from Los Angeles –one of the heaviest polluted urban areas in the US. The data are available at the EPA air trends site, which tracks every monitoring station.

Notice that the standard is the second-highest average for a 24-hour period, with the U.S. standard at 150. Also notice that the 75 mg/m3 that Paris returned to is still about as bad as it gets down in LA these days.

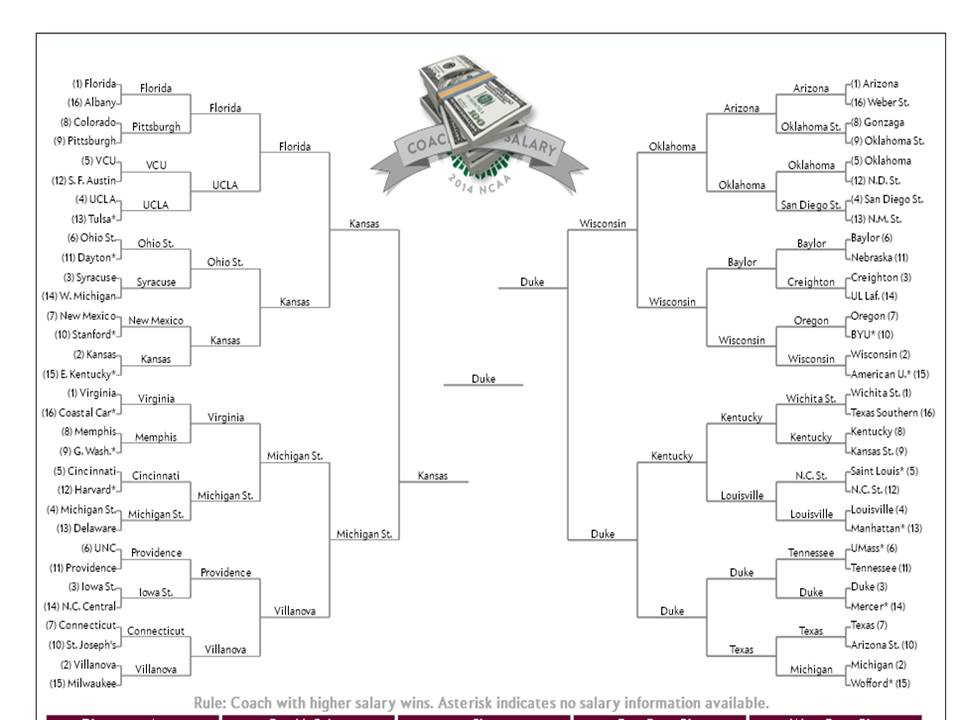

Slate has an ingenious interactive tool that fills in your NCAA bracket based on various criteria, including the schools’ academic rankings, distance to the area (nearer team wins), SAT scores (higher winning, inexplicably), and my personal favorite, dog friendliness.

But, as market economists, perhaps we should just let the market speak by looking at the most handsomely paid coaches!

As you may know, the highest-paid state employee in most states is the head football coach at one of the public universities. Here in Wisconsin, however, Madison’s coach Bo Ryan has that distinction, which is good enough for the highest-paid coach in that region. I’m guessing that Michigan State University coach Tom Izzo is the highest-paid employee in Michigan.

Not surprisingly, these look a lot like many of the actual “expert” picks for much of the tournament, including Michigan State reaching the Final Four as a four seed.

Although I like the idea of picking based on coach salary — what better measure of quality than willingness to pay for a coach?! — one suspects we can actually measure performance, so I tend to lean on the Logistic Regression Markov Chain model to inform my picks.

The Washington Post gives us a fascinating glimpse into the choice of the economics major (is there anything about economics that’s not fascinating?).

Executive Summary: Women are more grade sensitive than men.

The data are from an “anonymous research institution” and the relationship of interest is the choice of the economics major based on the grade in the introductory economics class. For students getting As, for example, about 40% of males and between 40 and 45% of females go on to major in economics. For males, that’s pretty much true whatever grade they get, but females appear to be far more responsive to lower grades. The starkest comparison is for the A and the B+ students. Approximately 40% of male students who get an A or B+ become majors, whereas for females there appears to be about a 30% dropoff in the probability of becoming a major as the grade goes from an A to a B+. The interpretation is that women are more grade sensitive than men, and as a result move on to a different discipline, where presumably their grades are likely to be higher.

Here’s Harvard’s Claudia Goldin:

“Maybe women just don’t want to get things wrong,” Goldin hypothesized. “They don’t want to walk around being a B-minus student in something. They want to find something they can be an A student in. They want something where the professor will pat them on the back and say ‘You’re doing so well!’ ”

“Guys,” she added, “don’t seem to give two damns.”

I wonder what percentage of men and women go into an economics class with the idea that they are going to major in the subject? One possibility is that more men plan to go into economics, and are less discouraged by a “low” grade. Notice that overall, between 30 and 40% of men who take that class wind up as majors. We also know that men account for just over 70% of majors. So if we assume an equal split of men and women in going into an intro class of 100 people at the school where the data were collected, we might expect 17.5 men and 7.5 women to wind up as majors.

Incidentally, I looked at the past several years of data and 35% of our graduating seniors have been women, which is a solid 20% higher than the national average of 29%.

As I wrapped up Econ 450 today, I told the class that the basic theoretical frameworks, including agency theory, should continue to pop up for as long as we both shall live. And here, from Wired, we have an agent (allegedly) trying to bilk the principal. The players should be familiar.

The Obama administration accused Sprint today of overcharging the government more than $21 million in wiretapping expenses…

Sprint… inflated charges approximately 58 percent between 2007 and 2010, according to a lawsuit the administration brought against the carrier today.

The Agent says it was just doing what it was told:

Under the law, the government is required to reimburse Sprint for its reasonable costs incurred when assisting law enforcement agencies with electronic surveillance,” Sprint spokesman John Taylor said. “The invoices Sprint has submitted to the government fully comply with the law. We have fully cooperated with this investigation and intend to defend this matter vigorously.”

It seems that the Principal gave the Agent plenty of opportunities:

According to records, the number of domestic federal and state wiretaps reported in 2012 increased 24 percent from the year earlier. Overall, a total of 3,395 wiretaps were reported in 2012. Of those, 1,354 were authorized by federal judges, and 2,041 by state judges. The number of federal orders jumped 71 percent. State orders increased 5 percent.

This past week President Burstein hosted a pizza gathering in anticipation of the annual 102-Day Senior Party. As the name indicates, the party marks only 102 days until Commencement for our out-going Seniors, assuming their Senior Experience papers get whipped into shape.

Though I was not able to attend (invitation lost, perhaps?), I see that the President’s gathering included some charter members of the Lawrence Curling Club, of which I am the faculty sponsor. Pictured is the president with some of our young curlers, who are no doubt explaining that “take out” is not pizza related, nor does “hog line” have to do with diners queuing for sausage pizza.

I am one of the contributors to the New York Times Room for Debate section today on Daylight Saving Time. My contribution has to do with the changes in pedestrian fatality risks and total fatalities associated with the time change. (UPDATE: There is also a piece up in the Sunday Appleton Post-Crescent).

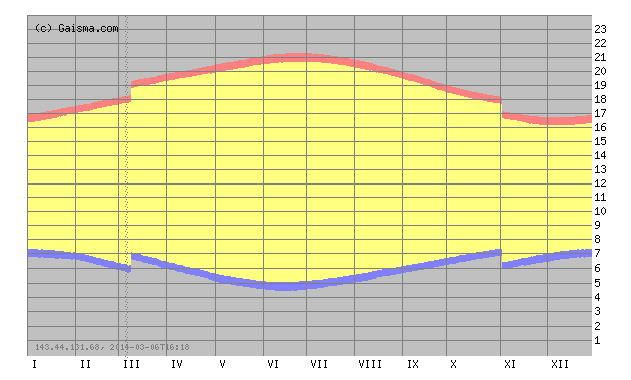

So, what does a time change look like? Glad you asked: The figure from the sunshine authority, Gaisma.com, shows daylight patterns for our own Appleton, Wisconsin. Each day starts with midnight at the bottom and goes to the top, and the months go left to right. The blue line is the dawn and the red the dusk.

The switch to DST in March and the switch back to standard time in November are clear — they are the discontinuities (the “breaks”) in the sunrise and sunset curves. Because we “spring ahead” one hour, the sunrise time on Sunday morning will be one hour later than it was on Saturday. An early morning walk that was in that daylight on Saturday will be in the dark on Sunday. To have a sunrise at the same time as Saturday’s, we will have to wait until early April. The opposite happens in the evening. Sunset will be one hour later starting on Sunday. There will be less light in the morning, but more light in the evening.

Light and visibility are extremely important determinants of traffic safety, particularly for pedestrians. Paul Fischbeck and I looked at data from 1999-2005 on fatalities and travel patterns, and determined that the morning risk increases about 30% per mile walked, while the afternoon risk falls close to 80%.

The figure below shows pedestrian fatality risks from 1999-2005. The blue and maroon bars show fatality risks per 100 million miles walked in March and April, respectively. Note that for the 6 a.m. time slot the risks increase about 30%, whereas for the 6 p.m. time slot the risks take a sharp nosedive. At midday the risks stay right about the same (we found no statistically significant difference in risks for that time period). Overall, total pedestrian fatalities decrease in the Spring both because risks fall more in the evening than they rise in the morning, and there are many more people out later in the day.

These data are rather crude in the presentation, as they do not focus specifically on the days leading up to and immediately following the time shifts, which is how researchers typically isolate the effects of the time change.

Here are some references for those interested:

S A Ferguson, D F Preusser, A K Lund, P L Zador, and R G Ulmer “Daylight saving time and motor vehicle crashes: the reduction in pedestrian and vehicle occupant fatalities,” American Journal of Public Health 1995 85:1, 92-95

J M Sullivan and M J Flannagan, “The role of ambient light level in fatal crashes: inferences from daylight saving time transitions,” Accident Analysis & Prevention, 2002 34:4, 487-498

D Coate and S Markowitz, “The effects of daylight and daylight saving time on US pedestrian fatalities and motor vehicle occupant fatalities,” Accident Analysis & Prevention, 2004, 36: 3 351-357

The Wall Street Journal reports that “Corporate Economists Are Hot Again.”

This:

With more data available than ever before and markets increasingly unpredictable, U.S. companies—from manufacturers to banks and pharmaceutical companies—are expanding their corporate economist staffs. The number of private-sector economists surged 57% to 8,680 in 2012 from 5,510 in 2009, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In 2012, Wells Fargo had one economist in its corporate economics department. Now, it has six.

And this:

The key to the revival of in-house economists, companies and economists say, is the need to digest huge amounts of data—from production volumes in overseas markets to laptop usage in urban areas—to determine opportunities and risks for companies’ business units, not just in the U.S. but around the world.

As those of you who read this blog probably already know, we think that life as an economist is pretty awesome. And it’s not just us saying it, either. Here’s Noah Smith from the Noahpinion blog who says it thusly:

People often ask me: “Noah, what career path can I take where I’m virtually guaranteed to get a well-paying job in my field of interest, which doesn’t force me to work 80 hours a week, and which gives me both autonomy and intellectual excitement?” Well, actually, I lied, no one asks me that. But they should ask me that, because I do know of such a career path, and it’s called the economics PhD.

“What?!!”, you sputter. “What about all those articles telling me never, ever, never, never to get a PhD?! Didn’t you read those?! Don’t you know that PhDs are proliferating like mushrooms even as tenure-track jobs disappear? Do you want us to be stuck in eternal postdoc hell, or turn into adjunct-faculty wage-slaves?!”

To which I respond: There are PhDs, and there are PhDs, and then there are econ PhDs.

The emphasis is mine and I scrubbed the links, but the sentiment remains. A highly recommended read for the thinking-about-a-Ph.D. set.

Have you ever wondered how to calculate your grade point average? If so, boy have you come to the right blog post.

Here’s what you need to do: Take your Grade in a given course and assign it the number of Points for that grade (e.g., an A is 4 points, A- 3.75 points, B+ 3.25 points, etc).*

Once you’ve taken care of that, multiply the number of Points by the number of Earned Units for that course. So, for example, if you earn an A in a six-unit course, your total quantity of points (Qty Points) would be 4 points for an A times 6 Earned Units = 24.

Now you can add up your total Qty Points and divide by GPA Units and, wah lah, you have your Grade Point Average.

As example, you take four courses in your first term, get a B in Freshman Studies, a B+ in Geology, and an S in Economics because you S/Ued the course, an a B in a one-unit piano performance course. Your grade point average would only include courses with grades and would be calculated thusly:

(3 points x 6 units + 3.25 points x 6 units + 3 points x 1 unit) / 13 units = 3.12

And if you’d like an Excel spreadsheet that does it for you, here it is (email Professor Galambos with comments or questions about the spreadsheet).

* A full list of Grade Points can be found here.