Today’s Financial Times indicates that Deloitte Touche Tommatsu plans to hire 50,000 workers per year over the next years. Take advantage.

Category: General Interest

The Liberal Arts and UCLA Economics

Again, welcome back to those returning to campus. I’m looking forward to getting back myself and cranking up the 300 class. Meanwhile, a few weeks ago we instituted a segment titled “free market Monday,” which will emphasize the ideas of some seriously pro-market economists.

In that spirit, here is a piece of interest from the latest edition of Econ Journal Watch — an interview with William Allen (of Alchian and Allen fame) about his path to a professorship UCLA, as well as the heyday of the UCLA economics department under the leadership of Armen Alchian (of Alchian; Alchian & Demsetz; Klein, Crawford, & Alchian fame, among others). Allen begins with a shout out to the liberal arts, as he extols the virtues of his time at Iowa’s Cornell College:

[E]specially for one who is headed for graduate work, there is much in favor of first attending a small liberal arts college. At Cornell, there was a great deal which could be learned about the various aspects of the world and its evolution in the mandatory year-long freshman courses in English, history, and the social sciences. The learning was facilitated by classes of small size taught by non-T.A.s, and by much interaction with fellow students in the dorms and dining halls. And one can be captain of the tennis team without being a professional jock.

I’m not sure that the mandatory nature of the courses was the linchpin of his undergraduate education (at least I hope not, since my alma mater has no such requirements), but certainly writing and discourse are important. Indeed, one of my professors in graduate school said that liberal arts students seemed to have a better feel for what an interesting question is.

Motivating Econ 101

Alex Tabarrok talks to NPR about the story he uses to motivate his 101 class at George Mason. It is a tale of the English shipping their prisoners off to Australia, with the sorry result that many of the prisoners perished during the sea voyage. Yikes. How could they have prevented this sorry fate? Oh, I just wonder.

Alex Tabarrok talks to NPR about the story he uses to motivate his 101 class at George Mason. It is a tale of the English shipping their prisoners off to Australia, with the sorry result that many of the prisoners perished during the sea voyage. Yikes. How could they have prevented this sorry fate? Oh, I just wonder.

Cowen and Tabarrok are authors of an introductory textbook that I am willing to endorse, at least on the micro side. They also blog at Marginal Revolution.

Carrots or Sticks Redux

A while back we took a look at Daniel Pink’s recent book, Drive: The Surprising Truth about what Motivates Us. Well, actually, instead of reading the book, we waited for the movie version from RSA Animate. For those of you interested in a bit more meat without  actually committing to reading, you might check out his TED talk or even his recent EconTalk interview with the always engaging Russ Roberts.

actually committing to reading, you might check out his TED talk or even his recent EconTalk interview with the always engaging Russ Roberts.

Pink seems to be as pervasive as whatever that pink stuff was in The Cat in the Hat Comes Back. A former speechwriter for Al Gore, he also has a pretty cool website and blog that ranges from the minutiae of the day to his Johnny Bunko career guide.

Extending the Bush Tax Cuts: A Mostly Resounding Yes

The Economist invites a group of economists whether the Bush tax cuts should be extended. For those of you who follow Washington politics, this has been a meat-and-potatoes contentious issue for some time, so I was interested to see what the big thinkers of the profession are saying.

To a man, the answer is some form of yes.

- Tom Gallagher of the International Strategy & Investment Group says, “Yes, but only for a short period.”

- Michael Bordo of Rutgers University says, “Yes, their benefits outweigh their costs.”

- A personal favorite of mine, Alberto Alesina of Harvard, recommends that we “maintain the cuts and reduce spending to trim deficits.”

- Columbia’s Guillermo Calvo exclaims, “Yes!, as the rich will drive recovery.”

- Only Oregon’s Mark Thoma offers a partial dissent, saying “only some, and the saved revenue should be recycled.”

A more complete accounting of the replies here. The responses are quick reads, and are filled with economic logic that you have probably heard somewhere before.

Or at least let’s hope so.

UPDATE: Former Obama OMB director Peter Orszag weighs in in today’s New York Times. More Thoma than Calvo.

Swoopo

Auctions have been around for many centuries, and those who have had some game theory know that there are many kinds. In some, you outbid others by offering more and more for the object being auctioned, in some the auction clock starts with a high price and descends until someone (the winner) yells “stop!” Most auctions have the winner pay the last bid, though some have the winner AND the next highest bidder pay, or even have every participant pay (all-pay auctions). I came across a newly popular type of auction that has been attracting quite a bit of attention. In a pay-per-bid auction, such as swoopo, your every bid increases the price by a set increment (such as one cent), but every bid costs you 60 cents. Some websites claim that these auctions are rip-offs, some advertise the great deals (and iPad for $11, a gold bar for $5, etc.). It’s fascinating to take a look at recently ended auctions on swoopo: here is someone paying $787 ($727 in bids and $60 in the final price) for a smart phone that swoopo says costs $620 and you can get for probably $100 less than that elsewhere. On the face of it, this looks like a large-scale and real-life variant of the dollar auction. What complicates this calculation is that one can bid on “bid packs” on swoopo, so the person winning that phone may have used bids that in fact cost him much less than the face value of those bids. There are only a few academic papers analyzing this new craze. For some interesting theory as well as empirical analysis, take a look at this paper. So how can it be profitable to sell a $100 Visa gift card for $1.98 to someone who used just 96 bids and thus got $100 for $60? Well, for the price to get to $1.98, 198 bids had to be placed. Ignoring the aforementioned possibility to buy bids at a discount, those 198 bids mean an income of 198x$0.60=$118.80. According to the paper cited above, the profit margins for swoopo are astounding.

Art Mart

Although economists as a whole are a pretty imperialistic bunch, the economic analysis of the art world has been a rather undeveloped field of inquiry. One notable exception is Northwestern’s David Galenson, who has published widely on the topic, and even developed a ranking system for the greatest art work based on “visual citations” (number 1 is Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.”)

Some of Galenson’s recent work examines how artists have earned a living over time and how that has shaped both the nature and creativity of their work. The New York Times piece cited above summarizes this argument:

To Mr. Galenson markets are what make the 20th century completely different from other eras for art. In earlier periods artists created works for rich patrons generally in the court or the church, which functioned as a monopoly. Only in the 20th century did art enter the marketplace and become a commodity, like a stick of butter or an Hermès bag. In this system, he said, breaking the rules became the most valued attribute. The greatest rewards went to conceptual innovators who frequently changed styles and invented genres. For the first time the idea behind the work of art became more important than the physical object itself.

It’s an interesting topic, especially for those interested in innovation and the arts. You might consider checking out Galenson’s book, Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art (available at The Mudd), for a fuller explication. You can read a summation of his argument over at my favorite clearinghouse, VoxEu, or yesterday’s piece in The American.

This might be a good I&E Reading Group selection or a building block for an independent study.

More on Teacher Performance

We recently posted a piece on the controversy surrounding the publication of teacher performance evaluations in Los Angeles. There are a couple of interesting follow ups circulating in our trusted news sources. The first piece is from the always contrarian and sometimes cantankerous Jack Shafer of Slate.com.

Nobody but a schoolteacher or a union acolyte could criticize the Los Angeles Times‘ terrific package of stories—complete with searchable database—about teacher performance in the Los Angeles Unified School District.

You probably don’t need to be a communications major to figure out where that piece is headed.

Shafer rightly applauds the LA Times FAQ page on what value-added analysis is, its strenghts and weaknesses, and other, well, FAQs.

A second piece plucked from the New York Times compares the pros and cons of value-added analysis in a more straightforward fashion. On the one hand:

“If these teachers were measured in a different year, or a different model were used, the rankings might bounce around quite a bit,” said Edward Haertel, a Stanford professor who was a co-author of the report. “People are going to treat these scores as if they were reflections on the effectiveness of the teachers without any appreciation of how unstable they are.”

On the other hand:

William L. Sanders, a senior research manager for a North Carolina company, SAS, that does value-added estimates for districts in North Carolina, Tennessee and other states, said that “if you use rigorous, robust methods and surround them with safeguards, you can reliably distinguish highly effective teachers from average teachers and from ineffective teachers.”

Certainly, the two sides each have a point. Even as a man of numbers (or perhaps, especially as one), I worry that people put too much faith in a quantitative rating. That said, it seems the cat has squirmed its way out of the bag on this one, and it is going to be difficult for opponents to get it back in.

10 Mistakes That Start-Up Entrepreneurs Make

For this piece, I refer you directly to Rosalind Resnick’s guest column in today’s Wall Street Journal. For those of you who have taken an entrepreneurship course, I’ll highlight numbers 9 and 10.

9. Not having a business plan

10. Over-thinking your business plan

Climate Change Updates

As far as I know, the climate is still changing, so nothing to update there. According to economists Matthew Kahn and Matthew Kotchen, however, we don’t seem to care as much about it (if “googling” is a good proxy for “caring”, that is). Ed Glaeser discusses this and some more of Kahn’s research in today’s NYT Economix blog post. One of the provocative points is the claim that climate change is a done deal, and that the big coming challenge is to adapt.

One person swimming against the apathy tide is the self-proclaimed skeptical environmentalist, Bjørn Lomborg. For years, Lomborg has been publishing pieces questioning the scale and scope of environmental problems. He has now reversed course and is calling for massive investments to tackle the problem. From my quick read, the tackling seems to be on the emissions side, as opposed to adaptation.

Anyone who has sat through my carbon capture and sequestration talk certainly knows I’m with the adaptation folks on this one. I simply am not convinced that the world can cut emissions enough to stabilize atmospheric concentrations, even under the most wildly-optimistic scenarios.

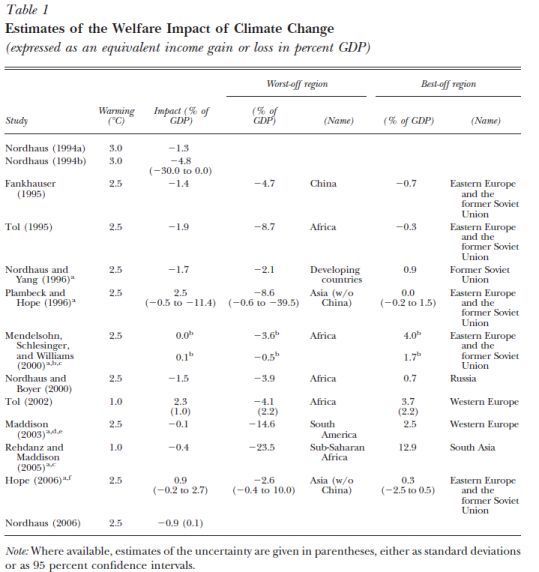

For a bit more meat on the climate change discussion, check out a recent symposium in the Journal of Economic Perspectives. Here’s a table of estimated net benefits across 13 studies.

Notice the overall impacts in terms of GDP per year seem to be on the order of -1% per year, though the estimate from the review author’s article (Richard Tol) shows net gains. You might also take note as to which countries are likely to win and lose in these estimates, and take that into account next time countries sit down to hammer out an agreement.

Should be an interesting century.

The Worst May Not Be Behind Us

Two days ago, I posted James Hamilton’s blog entry on Friday’s GDP numbers and suggested that the 1.6% growth in GDP was not as depressing as it might seem. Primarily, I noted that inventory growth had slowed and imports had risen. The latter might be viewed as demonstrating renewed economic strength whether the imports reflect increased household consumption and household income (which they do) or increased business purchases of intermediate inputs (which they also do.)

In today’s Financial Times, economists Carmen and Vincent Reinhart summarize their address given last week at the Kansas City Feds’ annual symposium which features central bankers from all over the world. The Reinharts warn us that financial crises of the sort we are emerging from do not generate robust rebounds.

Such optimism, however, may be premature. We have analysed data on numerous severe economic dislocations over the past three-quarters of a century; a record of misfortune including 15 severe post-second world war crises, the Great Depression and the 1973-74 oil shock. The result is a bracing warning that the future is likely to bring only hard choices.

But if we continue as others have before, the need to deleverage will dampen employment and growth for some time to come.

Although aggressive use of fiscal and monetary policies may be necessary to avoid the risks of economic depression, they are no substitute for changes in expectations and economic structure required to find a stable long term economic growth path. Attempts to avoid such “creative destructive” will only deepen the cost of the inevitable adjustment that must take place.

Not that Depressing!

On Friday, the second report on 2nd quarter GDP was released; it displayed GDP growth at 1.6% instead of 2.4%. The decline came from a downward revision in inventory buildup and an upward revision in imports. James Hamilton in his Econobrowser posting argues that the report suggests that the economy is still moving upwards though at a modest pace. It does not suggest a double dip recession. Hamilton provides some nice charts and tables to tell the tale. Check it out.

Color Me Impressed

The Denver Post has some way cool photos back from the early days of color photography. From potato pickers in Caribou, Maine to fishing in the swamp in Belzoni, Mississippi to homesteaders in Pie Town, New Mexico, these shots are generally fascinating.

Fermat’s Margin Call

For those of you who think passion is reserved for the humanities, check out this NOVA documentary on mathematician Andrew Wiles’ quest to solve Fermat’s last theorem. Wiles literally breaks down crying when thinking back to the moment when he thought he had it.

Fermat himself had said of the proposition, “I have a truly wonderful proof of this fact…. This margin is too small to contain it.” Though he probably didn’t, what his claim unleashed is extraordinary, with the Wiles’ proof being the last chapter.

Perhaps not.

Professor Sanerlib regularly shows this to his Math 300 class, but why should they have all the fun?

Absolutely awesome.

UPDATE: Alex Tabarrok at Marginal Revolution also spotted this and offers this:

The plainspoken Goro Shimura talking of his friend Yutaka Taniyama, “he was not a very careful person as a mathematician, he made a lot of mistakes but he made mistakes in a good direction.” “I tried to imitate him,” he says sadly, “but I found out that it is very difficult to make good mistakes.” Shimura continues to be troubled by his friend’s suicide in 1958.

Friday Food for Thought: “I’m an Economist”

John Kruk famously said, “I ain’t an athlete, lady, I’m a baseball player.”

For those of you who don’t know the (possibly apocryphal) tale, John Kruk was a rather fat man with a mullet, who could hit a baseball better than most people in the world. Kruk’s view was that it wasn’t any “athletic” gifts, per se, that allowed him to hit so well, but rather his crazy hand-eye coordination and phenomenal reflexes.

After a game, a woman spotted him smoking a cigarette and she started to give him the business about how an athlete shouldn’t smoke, his body is a temple, to think about the kids, and on and on.

His infamous response is the title of his autobiography.

So, what does this have to do with Friday Food for Though?. Well, when people find out that I’m an economist, they will typically say things like, “Oh, this must be a really interesting time for you.”

Why is that?

“Oh, you know, because of all the things going on in the stock market and the economy and stuff like that.”

Lady, I don’t know about that sort of thing — I’m an economist.

Or perhaps that’s what we economists are supposed to do — study the economy. Well, I guess that’s one answer, but I don’t think it’s my answer. I mean, I know something about what’s going on with the fiscal stimulus and the multiplier effect, but as Robert Barro points out, that it certainly not what I do.

Continue reading Friday Food for Thought: “I’m an Economist”

What Should Central Bankers Do To Address PLOGs?

Obviously, to answer this question begs another: What’s a PLOG? or perhaps: Should we view central bankers as plumbers? PLOG, a term coined by IMF economist Andre Meier, refers to Persistently Large Output Gap or positive deviation between potential GDP and measured GDP. The big concern raised by the LEX column in today’s Financial Times regards whether central bankers should worry about a deflationary double dip recession. As Lex puts it:

“The supposed PLOG-effect creates a dilemma: the Scylla of deflation or the Charybdis of extraordinarily easy monetary policy.”

Based on Meier’s study of 25 episodes in advanced economies, Lex argues that recessions slowly reduce inflation rates and generally stop prior to serious deflation. Therefore, central bankers should not become preoccupied with such a threat. Indeed, attempts to further stimulate economies such as ours with monetary policy is likely to be ineffective (or to use the proverbial idea: it’s like pushing on a string.)

I find the final sentence of the opinion piece particularly instructive.

“And while a PLOG may not create deflation, it can only amplify the grim economic effects of over-indebtedness, whatever policies central bankers adopt.”

Good Intentions, Bad Policy

In today’s Economix Blog, Edward Glaeser reminds us of a paradox that William Stanley Jevons posed in the 1800s. When public policy makes something more efficient (such as automobiles or electrical appliances), people may respond by expanded their use of the underlying product (gasoline or electricity). For example, CAFE standards, which seek to increase the gasoline efficiency of automobiles by requiring a higher miles per gallon standard for cars, may actually induce us to drive more. It all depends upon how much cheaper it is to drive, and the price elasticity of demand. We need to be sure that the adopted policy serves its ultimate objective, for example, to reduce an externality such as congestion or carbon emissions. As Glaeser puts it,

“Well-designed policies, like a congestion tax or carbon tax, can reduce social problems by getting the right sort of behavioral response; interventions that create an offsetting behavioral response can push the world in the wrong direction….The real lesson is that a change in the effective price of a commodity leads to a behavioral response, and, in some cases, that response can be so strong that it reverses the desired effect. As America considers new policies in public health, environmentalism and financial regulation, Jevons is as relevant as ever.”

Should Ideas Be Left to the Free Market?

The good folks at Organizations & Markets ask why economists haven’t paid closer attention to the economics of free speech. The classic piece on this is Ronald Coase’s “The Market for Goods and the Market for Ideas” (available from campus IP addresses). Coase asks why the rationale for goods’ market regulation doesn’t carry over into the realm of the market for ideas. Here is how he characterizes the prevailing attitudes:

In the market for goods, the government is commonly regarded as competent to regulate and properly motivated. Consumers lack the ability to make the appropriate choices. Producers often exercise monopolistic power and, in any case, without some form of government intervention, would not act in a way which promotes the public interest.

Fair enough. But then,

In the market for ideas, the position is very different. The government, if it attempted to regulate, would be inefficient and its motives would, in general, be bad, so that, even if it were successful in achieving what it wanted to accomplish, the results would be undesirable. Consumers, on the other hand, if left free, exercise a fine discrimination in choosing between the alternative views placed before them, while producers, whether economically powerful or weak, who are found to be so unscrupulous in their behavior in other markets, can be trusted to act in the public interest, whether they publish or work for the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune or the Columbia Broadcasting System.

Coase wrote the piece in the early 1970s, partly in response to federal regulation of commercial advertising, wondering whether there is a difference between firms schlepping products via commercial advertisements in the goods market is really any different than an article or an editorial in the New York Times.

Improbably, Time Magazine carried an article on Coase’s article and summarized his position nicely:

Coase challenged two assumptions that, he says, have created the distinction in public policy: 1) that consumers are able to distinguish good ideas from bad on their own, though they need help in choosing among competing goods; and 2) that publishers and broadcasters deserve laissez-faire treatment while other entrepreneurs do not.

It might be tempting for us to dismiss Coase’s argument as glib posturing, or as an example of economists being too clever for our own good. But how we define and constrain free speech is a central element of our political system. President Obama, in fact, spent his weekly radio address admonishing the recent Supreme Court decision that removed many legislative controls of corporate campaign financing. One would suspect that Coase was arguing to relax regulation of the goods market, not extend regulation to the ideas market, but the proliferation of the internet and other news sources has perhaps muddied the waters so much that the distinction is unrecognizable.

So, more to come, I suspect.

Should Efficiency Be Economists’ “Holy Grail?”

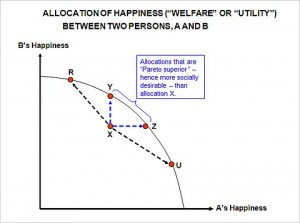

In today’s New York Times Economix Blog, Uwe Reinhardt poses the central question: “Is ‘More Efficient” Always Better?” In answer to the question he provides the basic definitions one would confront in an introductory economics course – including appropriate references to Pareto – and proceeds to point out that some efficient points, such as R and U, are not necessarily better than some inefficient ones (any in the region bounded by X, Y, and Z).

He then proceeds to link efficiency with optimality, which becomes his point of contention.

“One suspects that the term optimal came into widespread use among economists as a marketing device to promote their normative propositions based on efficiency. But as Professor Arrow warns his colleagues on this point:

A definition is just a definition, but when the definiendum is a word already in common use with highly favorable connotations, it is clear that we are really trying to be persuasive; we are implicitly recommending the achievement of optimal states.

Alas, it gets worse. Astute readers will have figured out by now that literally every point falling on the entire solid curve in the graph must be “Pareto optimal” by the economist’s definition of that term, not only those falling on line segment Y-Z. That circumstance makes the economist’s use of the word optimal even more dubious.”

In my view, Reinhardt stops in the wrong place. Rather than “dis” the term efficiency, he could differentiate between Pareto efficient (all points on the concave curve bounded by the two axes and called in this case the Happiness Possibility Frontier or HPF) and Pareto optimality (which employs Pareto’s notion that, at these points, to make someone better off, another person must be made worse off.) So what’s the point? Actually, there are two points to be made.

1. For any point (or allocation) below the HPF, that is any Pareto inefficient allocation, there exist Pareto improvement possibilities, and economists should encourage taking advantage of such.

2. Once on the HPF, Pareto optimal allocations depend upon social preferences, about which economists have no unique judgment to contribute; however, each such social choice judgment does yield consequences with opportunity costs (foregone choices) that can be identified. Stated differently, all Pareto efficient points are candidate points to be Pareto optimal under some set (of sometimes very curious) social preferences.

To conclude, the notion of efficiency is not a vague term, and it does reflect a value free standard. In my view, one can claim that for any Pareto inefficient allocation, Pareto improvements exist. Efficiency, however, says nothing about the optimal choice until preferences – in this case comparison of A’s vs. B’s happiness – is made. Furthermore, economists should encourage those making such social preferences to be transparent rather than hide them in 2000 pages of legislation.

Fallout Friday

I had seen some headlines earlier in the week about teachers unions being up-in-arms about an LA Times investigative series on teacher quality, but I hadn’t seen anything concrete until I saw Alex Tabarrok’s post at Marginal Revolution this morning.

All I can say is, wow!

The basic storyline is that the Times accessed data on changes in student performance from year-to-year and was able to match that up at the individual teacher level. The entire analysis isn’t published yet, but if you check out the snippet in the graphic below it is clear that the proverbial you-know-what is about to hit the you-know-where in the LA school system. And, yes, that is the real Miguel Aguilar and the real John Smith in there.

Ouch.

This is the sort of thing that might get Mr. Smith (and his union) to go to Washington (or Sacramento) — to quash this kind of information being revealed.

Tabarrok sums up his thoughts and I will simply repeat them because I have trouble disagreeing:

I don’t blame the unions for being up in arms and I feel for the teachers, for some of them this is going to be a shock and an embarrassment. We cannot simultaneously claim, however, that teachers are vitally important for the future of our children and also that their effectiveness should not be measured… Moreover, I see this as a turning point. Once parents have this kind of information who will allow their child to be in a class with a teacher in the bottom ranks of effectiveness? And if LA can do it why not Chicago and Fairfax?

Stay tuned on this one.