The picks are pouring in for our Second Annual Pick the Economics Nobel Prize contest (see here). The consensus pick around the department seems to be Paul Romer, so we might be dividing up that bag of M&Ms pretty thin if he wins.

Here are some more thoughts today from Tyler Cowen:

- Richard Thaler joint with Robert Schiller.

- Martin Weitzman and William Nordhaus, for their work on environmental economics

- Three prominent econometricians of your choice, bundled.

- Jean Tirole, possibly bundled with Oliver Hart and other game theorists/principle agent theorists. But last year the prize was in a similar field so the chances here have gone down for the time being.

- Doug Diamond, bundled with another theorist or two of financial intermediation, such as John Geanakopolos. Bernanke probably has to wait, although that may militate against the entire idea of such a prize right now.

- Dale Jorgenson plus ???? (Baumol?) for a productivity prize.

Thaler was my original (anomalous?) pick, though yesterday I hedged and went with Shiller. So this might be a case of great minds thinking alike, or of me being brainwashed by reading Marginal Revolution too often.

I like the Marty Weitzman pick better. Economics hasn’t given a prize for global climate change or for environmental work in general, and Weitzman has been a big deal forever for his canonical “prices versus quantities” paper, as well as for some more recent work on the “fat tail.” I’m not so sure about Nordhaus paired with him, however.

Professor Finkler has Paul Romer. I have yet to hear from my other colleagues, who are no doubt strategically plotting their picks as I type here.

PBS senior correspondent Ray Suarez will be on campus Tuesday to deliver the University Convocation lecture, “

PBS senior correspondent Ray Suarez will be on campus Tuesday to deliver the University Convocation lecture, “

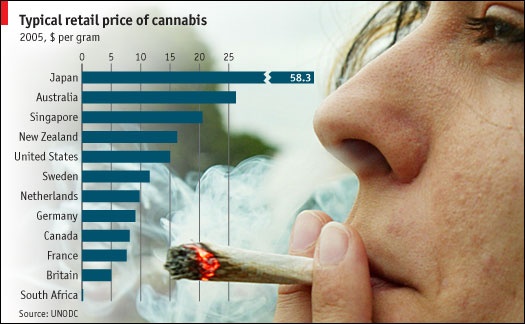

It is a good couple of weeks for those interested in the economics of (and innovation in) illicit drug markets. First, HBO started up its mega super miniseries,

It is a good couple of weeks for those interested in the economics of (and innovation in) illicit drug markets. First, HBO started up its mega super miniseries,