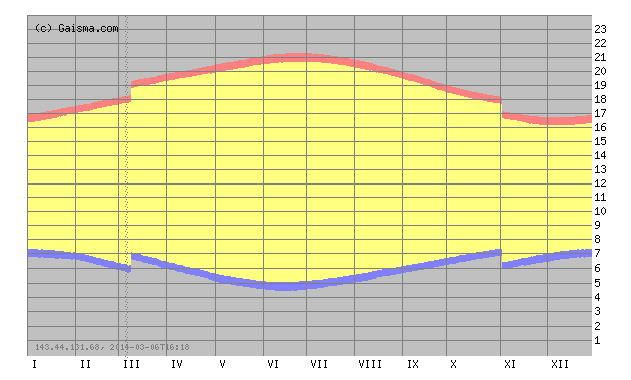

As I gear up for (count ’em) two environmental studies courses next term, I turn to Mother Jones for inspiration. And she delivers an extraordinary feature article on the environmental and energy implications of marijuana production. I can’t speak to the merits or accuracy of the article’s contentions, but I was struck by this bewildering assertion:

My guess is that, like most crop farming, marijuana cultivation would use a lot less energy per unit output if it was grown at scale. Indeed, it’s kind of hard to imagine that any indoor growing would be efficient at $0.15 kWh.

Even so, nine percent of electricity use seems incredibly high.