![]() For those of you driving somewhere for Reading Period, or for those of you who simply have trouble reading, Tim Harford offers up the best in economics podcasts, including the Financial Times podcasts.

For those of you driving somewhere for Reading Period, or for those of you who simply have trouble reading, Tim Harford offers up the best in economics podcasts, including the Financial Times podcasts.

Month: February 2011

Stuck in The Mudd

Looking to pick up some reading recommendations for the upcoming Reading Period? My pick is Tyler Cowen’s e-book, The Great Stagnation, which has been something of a sensation since its release (if by sensation you mean, which I do, a bunch of economists and policy wonks have been reading and reviewing it). Plenty of buzz about this one, and at $4, it is about the price of a magazine.

Looking to pick up some reading recommendations for the upcoming Reading Period? My pick is Tyler Cowen’s e-book, The Great Stagnation, which has been something of a sensation since its release (if by sensation you mean, which I do, a bunch of economists and policy wonks have been reading and reviewing it). Plenty of buzz about this one, and at $4, it is about the price of a magazine.

Just not that into Stagnation? We’ve got more. Professor Finkler also just recommended a slew of books to me, including these:

- Amar Bhide’s Call to Judgment

- Raghuram Rajan’s Fault Lines (see Professor Finkler’s brief comments here)

- Nouriel Roubini’s Crisis Economics: A Crash Course in the Future of Finance

- Baumol, Litan, and Schramm’s Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism

Most of these are stocked over on the shelves of The Mudd (subject to availability, of course), along with a constant stream of tasty new releases. Just scanning that RSS feed, I see Michael Lewis’ breezy The Big Short as an appetizer(library info; more on Lewis here). And the fascinating-looking title ![]() Entrepreneurship, innovation, and the growth mechanism of the free-enterprise economies edited by Sheshimski, Strom, and Baumol could be a very enticing main course. I might just go run that one down.

Entrepreneurship, innovation, and the growth mechanism of the free-enterprise economies edited by Sheshimski, Strom, and Baumol could be a very enticing main course. I might just go run that one down.

You might consider adding to that list Branko Milanovic’s new book, The Haves and the Have-Nots (discussed here), that I plan to order presently.

For those of you who only do things for credit, there is a rumor floating around the department that as a follow up to the Schumpeter Roundtable, we will be Discovering Kirzner by reading Israel Kirzner’s Competition and Entreprenuership this Spring term. It was also recently announced that the Spring Lawrence community read will be Cheap: The High Cost of Discount Culture. Professor Galambos and I are both signed up for that one.

Finally, I am right in the middle of Steven Johnson’s Where Good Ideas Come From, which my colleagues mostly seem to like. Something you can probably read in the car, if it wasn’t for the 6-point font footnotes.

Enjoy!

New Course

A new course possibly of interest to many of you will be offered next term. It was not on the books when you registered, so we are trying to let you know about it:

History 376: International Development in Historical Perspective

History of economic development theory, policy, and practice throughout the world since 1945. Particular focus will be given to the evolution of orthodoxy in this field, from modernization theory through dependency theory to neoliberalism, considering the performance and criticism of each. Case studies include African, Asian, and Latin American countries.

Taught on TR 12:30, the course requires sophomore standing and has no other prerequisites. It is taught by Michael Mahoney, a specialist on the history of Africa who taught at Yale for a decade (including this course).

Schumpeter Birthday Convocation

Mary Jane Jacob’s convocation lecture, “The Collective Creative Process,” is Tuesday at 11 at the Lawrence Chapel. Here is the lowdown:

Jacob is an independent curator known for her innovative, creative and collaborative projects Executive Director of Exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago, Jacobs has published many books and articles that examine ways to more fully involve the community into contemporary art by moving art out of “dead” museums and galleries into “living” spaces. Her work began in the early 1990s with the “Places with a Past” exhibition in Charleston, SC where she collaborated with 23 artists who each set up a public installation in Charleston in an attempt to tell the history of the city.

A scouring of the internet tells me that Jacob’s “name is synonymous with the phrase ‘art as social practice’ or the field of art that is now more widely known as ‘Relational Aesthetics.'” What that means, I am sure we will find out.

It is perhaps fitting that a faculty convocation celebrating “Innovation through Collaboration” coincides with the birthday of economist Joseph Schumpeter, who certainly needs no introduction on this blog.

But, of course, I am happy to give you one anyway.

Enjoy the Convo!

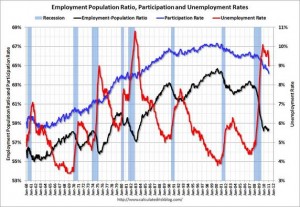

Jobs (slightly up) and the Unemployment Rate (downward trend)

Last Friday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the unemployment had fallen to 9.0%, a sizable drop from December’s 9.4% and November’s 9.8%. The BLS also released the payroll survey which indicated that the number of employed based on the non-farm payroll survey only increased by 36,000 in January. Such a small increase fails to keep up with trend labor force growth which averages about 125,000 per month (based on a civilian labor force of roughly 150 million that grows at about 1% per year.)

So is this good news or bad news? Actually, these two results are largely unrelated to one another. The unemployment rate is derived from a household survey which also revealed that the number of employed people rose by 117,000, that is almost the trend rate. The payroll survey tends to look at relatively older companies, which typically do not drive employment growth. James Hamilton, in a recent Econbrowser piece, lays out some of the relevant details. The chart below highlights key labor market patterns. The relatively low level of labor force participation puts downward pressure on the unemployment rate, which is why that indicator is not particularly informative with regard to the JOBS, JOBS, JOBS agenda. The details will entertain those of you who will take Econ 320 next term.

Blackout is Another Word for “Shortage”

No doubt you have heard (okay, perhaps I have some doubts) about the blackouts rolling across Texas this past week. Blackouts occur, of course, because the quantity of power demanded at a point in time exceeds the quantity of power supplied, leaving some folks literally in the dark. And out in the cold.

So, the key question is why power supply was insufficient. Michael Gilberson of Texas A&M provides a preliminary analysis of why Texas power producers failed to meet demand. The first reason is that it was very cold, so the demand for power increased. The cold also caused the power to decrease (!) as power plants themselves suffered outages due to frozen pipes at large coal-fired plants (didn’t their mothers ever tell them to leave the water dripping?).

Actually, that isn’t really the first reason. The real reason is likely Texas’ famous electricity isolationism; that is, the state deliberately lacks to infrastructure to export or to import electricity. Why would they pursue such a policy? To avoid federal (i.e., inter-state) regulation.

Here’s another explanation along the same line.

That electricity markets tend to be very complicated to understand, but supply and demand fundamentals are not.

Local Sports Team in Contest of Interest

The pride of the Fox Valley, the Green Bay Packers, will be mixing it up with my former hometown heroes, the Pittsburgh Steelers, at the Super Bowl. The game will take place, weather permitting, this Sunday in balmy Dallas, Texas.

Although the contest itself is predominantly of interest to denizens of northeastern Wisconsin and southwestern Pennsylvania, many from across the nation and around the world will tune in for antics of the mascots (pictured), the often-irreverent commercials, the many wagering opportunities, or simply as an excuse to feast on some tasty snacks (despite some unexpected side effects). Yum.

This year, we are also treated to some added intrigue by a number of touching personal-interest stories. Or if you aren’t into Olympics-coverage style tearjerkers, perhaps you’d like to see how some famous movie directors have portrayed the Big Game.

Econ majors might be interested in some of the simple economics of the Super Bowl (summary here), such as secondary-market ticket prices (more than you think) and estimated economic impacts (less than you think). You might also be interested to know that Green Bay punter Tim Masthay abandoned a lucrative career as an economics tutor at the University of Kentucky, where “he picked up anywhere from three to six hours a day as a tutor, helping student athletes … with economics and finance courses. That paid $10 an hour.”

$10 an hour? Not bad.

My allegiances here are more with the black-and-gold than the green-and-gold. Indeed, earlier this year communications director Rick Peterson introduced me as “a big Steelers fan,” so there you have it. I also made a friendly wager with Professor John Brandenberger on the outcome of the game (even spotting him the three points that the Packers were favored by at the time of the bet). I have a feeling I’m going to be buying over at Lombardi’s.

Though my heart is with the Steelers, I’m guessing that the general spirit of the community and quality of the celebratory culinary fare will be better with a Packers win.

Federal Spending — Actual and Affordable

Political Calculations has another wonderful, self-explanatory graphic:

Great blog. I’m going to add it to my recommendations.

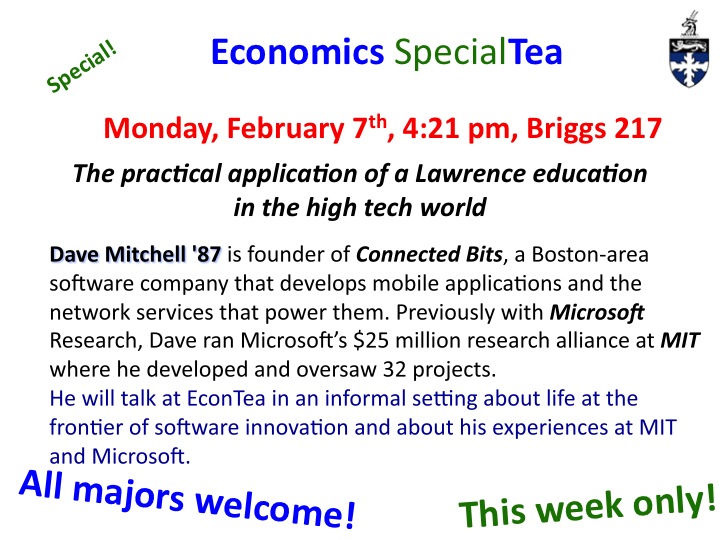

Economics SpecialTea w/ Dave Mitchell

Update: World Still Not Flat (at least not income distribution)

The New York Times reviews The Haves and the Have-Nots, what appears to be a fascinating new book from World Bank economist, Branko Milanovic. In addition to the review, the Economix blog features this extraordinary representation of world income distribution by country:

Milanovic has broken income (adjusted for purchasing power) by country down into twenty “ventiles.” So the lowest five percent of income earners are in the first ventile and the richest five percent are in the top ventile. What this piece shows is that the poorest of the poor in America are in the 70th percentile of world income. Compared with India — the average American in that first ventile has as much income (adjusted for purchasing power) as the richest Indian ventile.

I find that astonishing.

I also note with interest that there is a very steep ascent of the American distribution, indicating the poor here are really, really poor in relative terms, but the rest of the country is in pretty good shape. The median income in the US in comfortably in the top 10% of world income.

Well, I’m pretty happy, but maybe that’s just me.

America Unhappier, Death and Divorce Make People Sad

Professor Gerard recently wrote about the views of Schumpeter and Stigler on Intellectuals. In the paper he cites, Stigler wonders why Intellectuals hate economics, and considers the possibility that our extremely technical field and extremely poor communication style might have something to do with it:

Less than a century ago a treatise on economics began with a sentence such as, “Economics is a study of mankind in the ordinary business of life.” Today it will often begin: “This un- avoidably lengthy treatise is devoted to an examination of an economy in which the sec- ond derivatives of the utility function possess a finite number of discontinuities. To keep the problem manageable, I assume that each individual consumes only two goods, and dies after one Robertsonian week. Only elementary mathematical tools such as topology will be employed, incessantly.” (Stigler: The Intellectual and the Market Place)

A paper I looked at recently reminded me of another reason why many Intellectuals look askance at us economists: the long and solid tradition of “economic imperialism.” That is, the tendency of a number of economists to think that our economist’s toolbox can be (and should be!) used to explain just about anything that reasonably falls under the heading “social science.” The paper I referred to is Well-Being Over Time in Britain and the USA by David Blanchflower, and the abstract includes this:

Money buys happiness. People care also about relative income. Wellbeing is U-shaped in age. The paper estimates the dollar values of events like unemployment and divorce. They are large. A lasting marriage (compared to widow-hood as a ‘natural’ experiment), for example, is estimated to be worth $100,000 a year.

I agree that research on happiness is very much relevant to economics, but I can just see a psychologist or a sociologist or a humanist read that and not know whether to laugh or to cry. (And what’s up with talking like Tarzan?) Blanchflower looks at survey data (essentially asking people whether they are happy or not) over the past few decades and then runs a bunch of regressions. There is nothing wrong with that, except for a dozen issues that cast doubt on the conclusions and that have probably been the subjects of extensive research in psychology, sociology, history, and maybe even economics. Without passing judgment on Blanchflower (about whom I know nothing), I am pretty confident in saying that a number of papers in economists have been guilty of applying economic tools to broader problems without bothering to understand the broader literature (you know, what those “soft” social scientists write).