Spring 2010 Lawrence visiting speaker, and author of the Cartoon Introduction to Economics, Yoram Bauman explains why our political system cannot generate a constructive budget. There are no substitutes for his exposition. Enjoy!

Spring 2010 Lawrence visiting speaker, and author of the Cartoon Introduction to Economics, Yoram Bauman explains why our political system cannot generate a constructive budget. There are no substitutes for his exposition. Enjoy!

Category: General Interest

Alan Greenspan on Excessive Risk Avoidance

In today’s Financial Times, former U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan opines that we can carry risk aversion too far. Greenspan’s discussion parallels that posted by Professor Gerard related to the interview of Vernon Smith. In particular, Greenspan argues persuasively that the more we set aside to protect against once in 50 year or once in 100 year adverse events, the less capital we have to devote to productive activities. He cites bank reserves in excess of $1.5 trillion as excessive private risk aversion. Regarding public policy, he argues as follows:

What is not conjectural, however, is that American policymakers, in recent years, faced with the choice to assist a major company or risk negative economic fallout, have regrettably almost always chosen to intervene. Failure to act would have evoked little praise, even if no problems subsequently arose; but scorn, and worse from Congress, if inaction was followed by severe economic repercussions. Regulatory policy, as a consequence, has become highly skewed towards maximising short-term bail-out assistance at a cost to long-term prosperity.

This bias leads to an excess of buffers at the expense of our standards of living. Public policy needs to address such concerns in a far more visible manner than we have tried to date. I suspect it will ultimately become part of the current debate over the proper role of government in influencing economic activity.

Sustainable China Initiative

Speaking of web interviews, check out Professor Finkler talking about the Henry Luce Foundation grant for the Sustainable China initiative. A fluid speaker, indeed.

You can get the full story on the Lawrence homepage. The initiative includes this fall term’s Econ 209, Water, Politics, and Economic Development, which includes a trek to China in December.

Interview with Vernon Smith

Last week I had a discussion with Professor Azzi about the classic piece, “Market contestability in the presence of sunk (entry) costs,” where Vernon Smith and his colleagues examine the dynamics of market structure. They find that even with the same initial conditions, an industry sometimes winds up competitive and sometimes winds up characterized by market power, a finding that we may well flesh out in IO this fall.

With that in mind, I was pleased to see a link to a ReasonTV.com video interview with Smith making the rounds on the econ blogosphere. In the interview Smith — the pioneer of “experimental” economics — talks about how asset bubbles show up in the lab whether you want them to or not, and his assessment of the government’s bailout of many homeowners:

Forgiving debt is not a good idea, but you have to realize that we don’t face any good options. If it hadn’t been done, the banking system would likely have collapsed.

Aside from that note, Smith also touches upon the marginal revolution, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, and growing up through the Great Depression. An interesting half hour all around.

I recall seeing him speak about the troubled state of electricity regulation a few years back, where he said something to the effect of: “the regulators’ solution is to set average revenues equal to average costs, and it’s this sort of average thinking that got us into this mess.”

Great line!

On the Brink

There has been much consternation these past few weeks about the federal budget and the debt ceiling, with the possibility that the ratings agencies could downgrade the U.S. credit rating. While some cheer the possibility of a U.S. default as a necessary step to reign in spending, MIT economist Simon Johnson writes that such a default would yield rather unhappy consequences.

A government default would destroy the credit system as we know it. The fundamental benchmark interest rates in modern financial markets are the so-called risk-free rates on government bonds. Removing this pillar of the system—or creating a high degree of risk around U.S. Treasurys—would disrupt many private contracts and all kinds of transactions.

The result would be capital flight—but to where? Many banks would have a similar problem: A collapse in U.S. Treasury prices (the counterpart of higher interest rates, as bond prices and interest rates move in opposite directions) would destroy their balance sheets. There is no company in the United States that would be unaffected by a government default—and no bank or other financial institution that could provide a secure haven for savings. There would be a massive run into cash, on an order not seen since the Great Depression, with long lines of people at ATMs and teller windows withdrawing as much as possible.

Yikes.

But that’s not all:

Private credit, moreover, would disappear from the U.S. economic system, confronting the Federal Reserve with an unpleasant choice. Either it could step in and provide an enormous amount of credit directly to households and firms (much like Gosbank, the Soviet Union’s central bank), or it could stand by idly while GDP fell 20 to 30 percent—the magnitude of decline that we have seen in modern economies when credit suddenly dries up.

With the private sector in free fall, consumption and investment would decline sharply. America’s ability to export would also be undermined, because foreign markets would likely be affected, and because, in any case, if export firms cannot get credit, they most likely cannot produce.

Not exactly a rosy picture.

Does China Invest Too Large a Portion of Its Income?

A recent blogpost by Professor Gerard (with the supporting observations from Dr. Doom (Nouriel Roubini) suggests that the answer might be yes. At some point, this will be true, but I’m not sure that it will happen in the next few years.

As a recent visitor to the Middle Kingdom (last two weeks in June) and to the western part of the Middle Kingdom in particular (Guizhou Province), I observed an incredible amount of building. Housing construction continues its rapid pace and not just in the biggest cities (such as Guiyang) but in regional (within the province) outposts such as Kai Li and even fast growing counties (such as Danzhai.) Furthermore, the links among these places are made by new toll ways and long tunnels through the mountainous countryside. Airports and local road improvements are also underway.

Is it too much? Has the marginal product of capital become small or even negative? It’s too soon to tell. It must be noted that China is approaching 50% urbanization which suggests that interurban transport and urban housing will be needed along with other critical infrastructure pieces such as water filtration and waste water facilities. These items certainly have found their way into provincial budgets.

In a recent article in Seeking Alpha, Shaun Rein, the Managing Director of the China Market Research Group, begs to differ with Dr. Doom:

“However, most of Roubini’s conclusions are based on phantom facts, as is his evidence for why China will have economic problems. There is no direct flight between Shanghai and Hangzhou, nor is there a maglev train system connecting the two cities. Shanghai has two — not three — airports, and the last new one opened a dozen years ago, in 1999. Both the Hongqiao and Pudong airports have been adding runways and terminals because the airports are too crowded, contrary to Roubini’s suggestions of emptiness. Pudong’s passenger and cargo traffic grew 27% in 2010, to 40.6 million passengers. It is now the third busiest airport in the world in terms of freight traffic, with 3,227,914 metric tons handled every year. Continue reading Does China Invest Too Large a Portion of Its Income?

“The closer you look, the worse it gets”

The economic situation in Greece is downright gruesome, and I have to wonder how bad the social unrest is to become there. The principal source of my pessimism is a piece from last October where Michael Lewis essentially argues that the situation is hopeless:

But beyond a $1.2 trillion debt (roughly a quarter-million dollars for each working adult), there is a more frightening deficit. After systematically looting their own treasury, in a breathtaking binge of tax evasion, bribery, and creative accounting spurred on by Goldman Sachs, Greeks are sure of one thing: they can’t trust their fellow Greeks.

I saw a couple of updates to that unhappy picture this week. First up, James Surowiecki in the New Yorker gives an accounting of Greece’s rampant tax evasion, a point Lewis also makes rather starkly. Indeed, the Surowiecki piece reads like an Executive Summary of Lewis’s article, with each arguing that the social and cultural aspects in Greece are broken and are effectively impossible to fix.

The second piece is from Tyler Cowen in the New York Times, where he argues that the situation is pretty dire even without factoring in the social difficulties of implementing meaningful policy reform. Cowen’s piece discusses some of the difficult choices facing the EU, and reminds us that lurking in the background are the potentially large problems of EU members from Italy to Portugal to Spain. Cowen doesn’t have much hope, concluding that “There’s a lot of news on the way, but probably very little of it will be good.”

Well, enjoy your weekend!

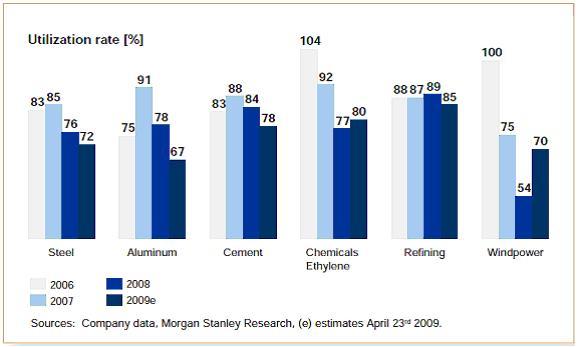

Is China’s Capacity Too Big Not to Fail?

I was having a discussion with one of my colleagues about Chinese economic growth prospects, and I invoked this Nouriel Roubini (a.k.a., Dr. Doom) piece, “China’s Bad Growth Bet.” The basic argument is that China is overcapitalized and this will lead to problems:

China has grown for the last few decades on the back of export-led industrialization and a weak currency, which have resulted in high corporate and household savings rates and reliance on net exports and fixed investment (infrastructure, real estate, and industrial capacity for import-competing and export sectors). When net exports collapsed in 2008-2009 from 11% of GDP to 5%, China’s leader reacted by further increasing the fixed-investment share of GDP from 42% to 47%.

Thus, China did not suffer a severe recession – as occurred in Japan, Germany, and elsewhere in emerging Asia in 2009 – only because fixed investment exploded. And the fixed-investment share of GDP has increased further in 2010-2011, to almost 50%.

The problem, of course, is that no country can be productive enough to reinvest 50% of GDP in new capital stock without eventually facing immense overcapacity and a staggering non-performing loan problem. China is rife with overinvestment in physical capital, infrastructure, and property. To a visitor, this is evident in sleek but empty airports and bullet trains (which will reduce the need for the 45 planned airports), highways to nowhere, thousands of colossal new central and provincial government buildings, ghost towns, and brand-new aluminum smelters kept closed to prevent global prices from plunging.

Thoughts on The Big Short

I finished up Michael Lewis‘s The Big Short and I think I found it worthwhile and poignant. It’s a character-driven piece that follows some of the players — as the title suggests — who shorted the housing market and went to the bank. To Lewis’s credit, he seems to do a pretty good job of explaining the crazy financial instruments created and deployed to bet against subprime mortgages. To my debit (?), I still don’t understand what was going on with all of this.

The big villains of the story are certainly the ratings agencies, who could have stopped much of this chicanery in its tracks by rating garbage as garbage rather than as AAA investment-grade bonds. But, perhaps a pithier point comes in the book’s denouement and is worth quoting at some length:

The people on the short side of the subprime mortage market had gambled with odds in their favor. The people on the other side — the entire financial system, essentially — had gambled with odss against them. Up to this point, the story could not be simpler. What’s strange and complicated about it, however, is that pretty much all the important people on both sides of the gamble left the table rich… Continue reading Thoughts on The Big Short

Old School Essay and Book Recommendation (Summer Reading, Part 3)

In a piece dear to the hearts of all my Econ 300 students, Master of rhetoric Deidre McCloskey lays out the case for teaching old school, Chicago economics. Although I certainly beat the maximize! drum, the central intuition is certainly that profits drive economic activity in the long run. McCloskey traces the historical context back to Adam Smith:

The core of Smithian economics, further, is not Max U. It is entry and exit, and is Smith’s distinctive contribution to social science… He was the first to ask what happens in the long run when people respond to desired opportunities. Smith for example argues in detail that wage-plus-conditions will equalize among occupations, in the long run, by entry and exit. At any rate they will equalize unless schemes such as the English Laws of Settlement, or excessive apprenticeships, intervene. Capital, too, will find its own level, and its returns will be thereby equalized, he said at length, unless imperial protections intervene.

The essay is interesting throughout, and I certainly approve of her message on this point.

If you like the rhetoric of this piece, you might consider checking out some of McCloskey’s other works, as she is indeed a prolific writer. One recent add to my summer reading list is her update of The Rhetoric of Economics. In it, she argues that “economics is literary,” and that making a persuasive case is “done by human arguments, not godlike Proof.”

This is one of McCloskey’s continuing projects. This one began with her work in the 1980s, and continues to be discussed today. The preface to the second edition, in fact, begins with a discussion of why more people didn’t read past chapter 3 in the first edition.

Why didn’t the fiscal stimulus have large effects on employment?

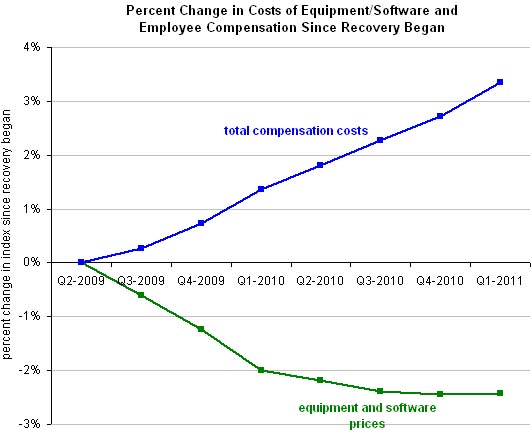

As noted previously, cheap capital and expensive labor tend to lead to the substitution of capital for labor – after all capital is often called “labor saving devices” for a reason. Now, we have solid evidence that the total cost (wages or salary and benefits) of labor has risen markedly while equipment and software costs have fallen since 2009.

For the rest of the story, see Catharine Rampall’s NY Times Economix blog last Friday entitled “Man vs. Machine.” To put it most starkly, if your job can be replaced by an algorithm, it probably will be. As those who took Econ 320 should know, if you attempt to implement macroeconomic stabilization policy without understanding the microeconomics of labor markets, you may not be blessed with success.

Why Go to College?

With reunion upon us, it is an excellent time to ask, “why go to college?” Indeed. To help us out with that question, Louis Menand has a provocative piece in a recent New Yorker examining the ins and outs of this exact question. As I got a few paragraphs into this one I started to wonder why this question gets discussed so rarely. It hardly seems self-evident, but I would guess it’s some combination of “expand your mindset,” “expand your skill set,” and “expand your wallet.”

With reunion upon us, it is an excellent time to ask, “why go to college?” Indeed. To help us out with that question, Louis Menand has a provocative piece in a recent New Yorker examining the ins and outs of this exact question. As I got a few paragraphs into this one I started to wonder why this question gets discussed so rarely. It hardly seems self-evident, but I would guess it’s some combination of “expand your mindset,” “expand your skill set,” and “expand your wallet.”

Of course, Menand is a more eloquent writer than I am, and he posits two theories, with the first one going something like this:

College is, essentially, a four-year intelligence test. Students have to demonstrate intellectual ability over time and across a range of subjects. If they’re sloppy or inflexible or obnoxious—no matter how smart they might be in the I.Q. sense—those negatives will get picked up in their grades. As an added service, college also sorts people according to aptitude. It separates the math types from the poetry types. At the end of the process, graduates get a score, the G.P.A., that professional schools and employers can trust as a measure of intellectual capacity and productive potential. It’s important, therefore, that everyone is taking more or less the same test.

That seems like a riff on the “expand your wallet.” The second has more to do with expanding horizons:

College exposes future citizens to material that enlightens and empowers them, whatever careers they end up choosing. In performing this function, college also socializes. It takes people with disparate backgrounds and beliefs and brings them into line with mainstream norms of reason and taste. Independence of mind is tolerated in college, and even honored, but students have to master the accepted ways of doing things before they are permitted to deviate. Ideally, we want everyone to go to college, because college gets everyone on the same page. It’s a way of producing a society of like-minded grownups.

At Lawrence, we recruit students based on our mission in the liberal arts, so I’m not sure if you could pigeonhole us into either of those categories. But we certainly make the claim that we train people to think and communicate, which are not explicitly vocational skills, but do come in handy.

Menand is certainly sympathetic to our cause, here and elsewhere, and makes some interesting points about our students. One is the results of the Collegiate Learning Assessment — a test designed to see if students learn anything in college:

The most interesting finding is that students majoring in liberal-arts fields—sciences, social sciences, and arts and humanities—do better on the C.L.A., and show greater improvement, than students majoring in non-liberal-arts fields such as business, education and social work, communications, engineering and computer science, and health.

Trade Agreements and Transitional Costs for Workers

As with many aspects of economic policy, political leadership – such as it is – often snatches defeat from the jaws of victory. Presently, the United States has the opportunity to sign trade agreements with Columbia, South Korea, and Panama that will provide great opportunities for U.S. exporters without having to offer special privileges or changes in domestic markets related to products from these countries.

As with many aspects of economic policy, political leadership – such as it is – often snatches defeat from the jaws of victory. Presently, the United States has the opportunity to sign trade agreements with Columbia, South Korea, and Panama that will provide great opportunities for U.S. exporters without having to offer special privileges or changes in domestic markets related to products from these countries.

Why might Columbia, South Korea, and Panama want to sign these apparently one-sided agreements? One answer is their economies would benefit greatly from better access to goods from the U.S. Why have we resisted signing these agreements? Many advocates in these country believe that trade hurts domestic workers. This certainly is true in the short run for workers whose jobs end because the products they produce no longer are competitive with imports. It’s also true when capital investment, often spurred by low interest rates, encourages the substitution of capital for labor. Neither of these concerns, however, are pertinent for the trade policy opportunities before us.

Passage of the aforementioned trade deals seems to be based on support for expanded trade assistance, a policy that provides specific benefits to some who can prove that they have lost jobs as a consequence of import competition. Matthew Slaughter and Robert Lawrence in today’s Opinion Pages of the New York Times argue that both more trade and more aid make sense, but the aid should not be specifically focused on those who allegedly lost jobs as a result of imports. They propose an innovative program that combines the existing trade adjustment policy with unemployment compensation benefits to create a new, more efficient safety net that, among other things, helps workers retool for different jobs and provides funds for health insurance in the interim.

I hope, but am not too optimistic, that our Congressional leaders, will recognize the equity and efficiency improvements offered by both the trade deals and the Slaughter-Lawrence proposal, pass the trade agreements for the aforementioned countries, and craft a new, improved safety net designed to help with labor market and structural unemployment transitions.

What’s the Wurst that Could Happen?

Today marks the opening of a summer ritual here at Lawrence, Griff’s Grill on Boldt Plaza. Mr. Griff will be out there grilling and spreading joy every Wednesday this summer, 11:30 AM – 1 PM. The menu is your basic hot dogs and brats, and featuring the alleged largest mustard bar north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

See you there.

Come to think of it, he does speak kind of softly

There was plenty of excitement this past Sunday at the Lawrence University Commencement, and the Appleton Post-Crescent seems to have captured much of it in this nice little photo layout.

Obviously, you can’t tell the players without a scorecard, so that on your left is the faculty Marshall, Professor of Mathematics Alan Parks, wielding the ceremonial (at least let’s hope so) faculty mace.

Below we have one of our graduating seniors, Karl Hailperin, who distinguished himself as an enthusiastic student, an avid reader, a stalwart at EconTea, and an all around good guy. He will definitely be missed.

Enjoy the photos!

Summer Reading, Part 2

I am not sure what I’ll be reading this summer, but I’m happy to share some of my candidates for summer reading. In any case, these might be worth considering for your summer reading list.

I have been interested in information theory for some time, and James Gleick’s The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood looks like great summer reading. It is accessible and broad-ranging, as far as I can tell so far. If you are interested in the technical details, something like the Elements of Information Theory by Thomas Cover and Joy Thomas will help.

I heard Larry Robertson talk about entrepreneurship at a symposium this year, and I was very impressed by how he approached the topic. So, I am interested in learning more about his approach from his book, A Deliberate Pause: Entrepreneurship and Its Moment in Human Progress.

When countries are ranked according to how important a role entrepreneurship plays in their economies, Israel almost always comes out near the top. In their book Start-Up Nation: The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle, Dan Senor and Saul Singer look at the possible reasons. I am half-way through the book, and I like how the authors try to offer as nuanced a view as they can. In searching for reasons, it is often tempting to run with a “simple” cultural explanation. While culture certainly must play a role, there are many other important factors, sometimes interacting with culture. I am especially interested in how government policy has enabled the blossoming of entrepreneurial ventures.

Following my interest in entrepreneurship in the arts, I hope to get to Why Are Artists Poor? The Exceptional Economy of the Arts, by Hans Abbing. The author is both an artist and an economist, so I am hoping for some really well-informed and rigorous analysis.

Moving on to innovation, I can’t wait to read Inside Real Innovation by Fitzgerald, Wankerl and Schramm. Professor Brandenberger has built up my expectations quite a bit through his enthusiastic summary of some of the main arguments, including the emphasis on the non-linearity of the process of innovation.

Well, if you get to any of those, let me know what you think. I will definitely read something more literary as well, but I am really not sure what that will be. In addition, I hope I’ll have a chance to listen to some great live music every now and then, and I wish you the same.

Summer Reading, Part 1

Now that Commencement has passed, we can get on with our summers. For me, that means I can try to take a bite out of the big, tasty stack of books I have been accumulating over the past 9 months.

Now that Commencement has passed, we can get on with our summers. For me, that means I can try to take a bite out of the big, tasty stack of books I have been accumulating over the past 9 months.

These are my picks:

Michael Lewis, The Big Short. Almost anything by Lewis is fun to read. I was plussed* by the series he did for Vanity Fair, and recommend those highly. Last year we read his classic, Moneyball.

Peter Drucker, Innovation & Entrepreneurship. This summer’s Reading Group pick.

Tim Harford, Adapt: Why Success Always Starts with Failure. Harford writes beautifully (well, for a guy on the economics beat) and his explanations are generally lucid, convincing, and theoretically sound. More on Harford here.

Daniel Okrent, Last Call. Tyler Cowen calls this history of U.S. prohibition “a masterpiece.” I am interested in the causes and consequences of criminalization of drugs and alcohol, and I am guessing excerpts of this will end up on my political economy reading list. Perhaps a course on the subject?

Ron Howard and Clint Korver, Ethics (for the real world): Creating a Personal Code to Guide Decisions in Work and Life. Howard is considered the father of decision science by many (and founder of the purple balls!). Korver is a successful entrepreneur and fellow Grinnell alum! I like this quote on “ethical dilemmas,” which they say is often fundamentally misunderstood:

“When we pick up just about any newspaper, we read about people caught in ‘ethical dilemmas.’ But nine times out of ten, they are not dilemmas at all. They are conflicts between prudential gain and ethical action. They are issues of temptation.” (p. 38).

Yup.

Philip Mirowski, Science Mart: Privatizing American Science. This looks like a clear winner. A historian I sometimes fraternize with is excited about this one, and I hear that “Mirowski is a wild man.” Let’s hope so. Expect to see this in Econ 450.

F.A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom. Following the Schumpeter Roundtable and Discovering Kirzner, we are picking up Hayek this fall as our department reading pick.

Jonathan Franzen, Freedom. Well, I am going to be on the beach for a week.

*It’s possible that “plussed” isn’t a word. Perhaps it should be.

Professor Corry Picks Up Some Hardware

Assistant Professor of Mathematics and charter member of the I&E Reading Group, Scott Corry, won the Young Teacher Award for — you guessed it — his teaching excellence. Provost Burrows awarded Corry with the honor at the 2011 Lawrence University commencement ceremonies this past Sunday.

Professor Corry exhibits the characteristics of a prototypical liberal arts teacher-scholar. In addition to being a gifted mathematician, he is a man of varied intellectual pursuits — a champion of the Freshman Studies program, an avid community reader, and probably a lot of other things he doesn’t tell me about.

For us down on Briggs 2nd, he has established himself as a pillar of our I&E Reading Group, having plowed through the likes of Schumpeter, Kirzner, and now Drucker. We look forward to reading and discussion with him for years to come.

So a warm congratulations from your friends in the economics department!

And they’re off… 2011 Commencement

We say farewell to our seniors with a repost from last year.

In our continuing attempt to understand the world around us, today we will talk about the tradition of wearing cap & gowns for graduation ceremonies.

Well, the first thing you need to know is that this dates back nearly 1000 years, and the academy is a notoriously conservative place. In the words of F.M. Conrford, in his advice to young academics, “Nothing should ever be done for the first time.”* The corollary is that once we get started on something, it’s tough getting us to stop.

With that in mind, Slate.com tackles the regalia question for us:

Standard fashion around 1100 and 1200 A.D. dictated long, flowing robes and hoods for warmth; the greater a person’s wealth, the higher the quality of the fabrics. This attire went out of style around the Renaissance. But sumptuary laws, often designed to prevent people from dressing above their class, kept academics (who were relatively low in the social hierarchy) in simple, unostentatious robes through the 16th century. Thereafter, academics and students at many universities wore robes for tradition’s sake. At Oxford, robes were de rigueur until the 1960s and are still required at graduation and during exams.

And, of course, the Americans played along:

When American universities sprang up in the 17th and 18th centuries, they adopted many Oxbridge academic traditions, including robe-wearing… Continue reading And they’re off… 2011 Commencement

“No more gorillas in hysterical herds”

On Sunday, former Senator Russ Feingold will pick up an honorary degree and deliver our Commencement speech as our seniors prepare to march off in glory. Feingold was a notoriously independent voice, as evidenced by his lone vote against the PATRIOT Act. Illustrating the odd second dimension of American politics, this week Tea Party hero, Rand Paul, nearly derailed the reauthorization of the PATRIOT Act by fundamentally siding with Senator Feingold’s position on the encroachment of federal power.

Indeed, the libertarian press shed a tear for Feingold, even comparing him to the incomparable Wisconsin icon, Robert LaFollette.

As H.L. Mencken wrote of the original LaFollette:

There is no ring in his nose. Nobody owns him. Nobody bosses him. Nobody even advises him. Right or wrong, he has stood on his own bottom, firmly and resolutely, since the day he was first heard of in politics, battling for his ideas in good weather and bad, facing great odds gladly, going against his followers as well as with his followers, taking his own line always and sticking to it with superb courage and resolution.

Suppose all Americans were like LaFollette? What a country it would be! No more depressing goose-stepping. No more gorillas in hysterical herds. No more trimming and trembling. Does it matter what his ideas are? Personally, I am against four-fifths of them, but what are the odds?…You may fancy them or you may dislike them, but you can’t get away from the fact that they are whooped by a man who, as politicians go among us, is almost miraculously frank, courageous, honest and first-rate.

So farewell to Feingold.

Indeed, I bet civil libertarians miss Senator Feingold on the floor, as he and Paul would have made for interesting bedfellow. Here’s Lynne Kiesling at Knowledge Problem on some recent trends in security versus liberty tradeoffs.