One of my more clever colleagues was telling me how impressed he was with the noticeable effects of our Freshman Studies curriculum, even extending well beyond affecting just Lawrence students and faculty.

How can he be so sure?

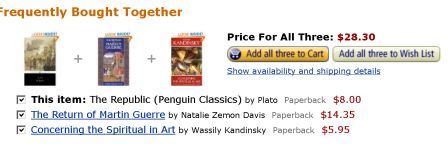

Just check out the similarities between this year’s Freshman Studies reading list and the frequently bought together books at Amazon.com.

So, how do you like that? Some guy camped out in the mountains looking to pick up a copy of The Republic is suddenly prompted to buy a copy of Martin Guerre?

We should have negotiated a lower price.

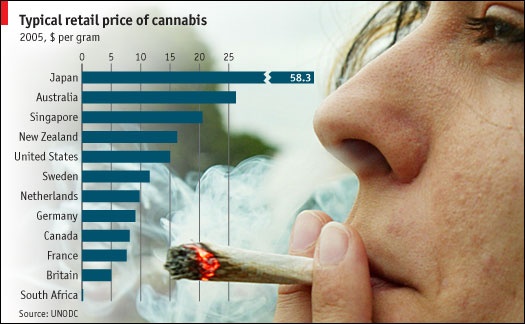

It is a good couple of weeks for those interested in the economics of (and innovation in) illicit drug markets. First, HBO started up its mega super miniseries,

It is a good couple of weeks for those interested in the economics of (and innovation in) illicit drug markets. First, HBO started up its mega super miniseries,

We would like to engage students who have a good understanding of micro theory and are interested in innovation and entrepreneurship. The readings dovetail nicely with my Economics 400 (IO) and 450 (theory of the firm) courses.

We would like to engage students who have a good understanding of micro theory and are interested in innovation and entrepreneurship. The readings dovetail nicely with my Economics 400 (IO) and 450 (theory of the firm) courses.