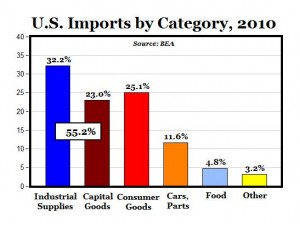

No doubt you have heard (okay, perhaps I have some doubts) about the blackouts rolling across Texas this past week. Blackouts occur, of course, because the quantity of power demanded at a point in time exceeds the quantity of power supplied, leaving some folks literally in the dark. And out in the cold.

So, the key question is why power supply was insufficient. Michael Gilberson of Texas A&M provides a preliminary analysis of why Texas power producers failed to meet demand. The first reason is that it was very cold, so the demand for power increased. The cold also caused the power to decrease (!) as power plants themselves suffered outages due to frozen pipes at large coal-fired plants (didn’t their mothers ever tell them to leave the water dripping?).

Actually, that isn’t really the first reason. The real reason is likely Texas’ famous electricity isolationism; that is, the state deliberately lacks to infrastructure to export or to import electricity. Why would they pursue such a policy? To avoid federal (i.e., inter-state) regulation.

Here’s another explanation along the same line.

That electricity markets tend to be very complicated to understand, but supply and demand fundamentals are not.

Invited experts also play critical roles in the program‘s core courses, including Innovation. These experts also help the program grow, expanding opportunities for students to engage in real-world entrepreneurship and innovation, through structured practical opportunities to take their course-based projects to commercialization, or internships in businesses or nonprofits that foster entrepreneurship or innovation. The NCIIA grant will help pay for travel expenses of several highly regarded experts who will contribute to the next offering of the Innovation course. The expectation is that students who take I&E courses will gain knowledge and cognitive skills that will equip them to be “change agents.” Combined with LU‘s emphasis on critical thought and information synthesis, the conceptual and practical knowledge gained through these courses will prepare students to undertake imaginative and ambitious innovative and entrepreneurial activities.

Invited experts also play critical roles in the program‘s core courses, including Innovation. These experts also help the program grow, expanding opportunities for students to engage in real-world entrepreneurship and innovation, through structured practical opportunities to take their course-based projects to commercialization, or internships in businesses or nonprofits that foster entrepreneurship or innovation. The NCIIA grant will help pay for travel expenses of several highly regarded experts who will contribute to the next offering of the Innovation course. The expectation is that students who take I&E courses will gain knowledge and cognitive skills that will equip them to be “change agents.” Combined with LU‘s emphasis on critical thought and information synthesis, the conceptual and practical knowledge gained through these courses will prepare students to undertake imaginative and ambitious innovative and entrepreneurial activities.