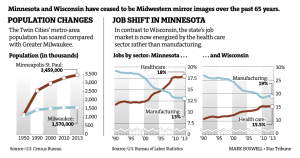

Those of you interested in international financial markets probably noticed there have been some rather dramatic changes in the the major stock indices over the past week. The US benchmark Dow Jones Industrial Average stood at 17, 345 last Thursday and subsequently plummeted to 15,666 at the close of business Tuesday. Following a turbulent Friday and some bad news from China on Monday, the Dow went into a free-fall on Monday, losing over 1,000 points before closing 588 points lower.

On Tuesday, the Dow seemed to regain some of its mojo, soaring 442 points in early trading. That mojo was a no-go, however, and by the end of the day the Dow had shed another 205 points. Ouch.

On Wednesday things really did turn around, with the Dow closing 619 points higher, the third-largest gain ever in absolute terms. As of this writing on Thursday, the Dow is up another 200 points, continuing to scratch back some of the losses from last week. (Wait, now it’s only up 150 points, better post this picture before it changes again):

The causes of these wild gyrations are quite varied, and would be difficult to explicate before the market moves a hundred points in either direction (that is, even if we knew what all of those causes were, which I’m not convinced that we do). The question for the decision maker is what do these market fluctuations mean to you?

Well, many flesh-and-bone economists will tell you with a straight face that you are either in the market or you’re not, so if you want to get out now, you shouldn’t have been in the first place. If you are in, you should just sit tight.

Although that might seem preposterous to you, what economists will tell you is that the idea that you can either predict or time the market is even more preposterous. More on this after the bump: Continue reading In your life expect some trouble, when you worry you make it double…