H. Spencer Banzhaf has a very cool piece in the new Journal of Economic Perspectives on the intellectual history of the concept of the value of a statistical life (VSL). This evidently owes some debt to work at the RAND Corporation, where analysts were addressing the “classic problem” of maximizing damages to the enemy subject to a budget constraint. The proposed solution of sending up lots of vulnerable decoy planes to distract the Soviets, however, hit a snag with the Air Force:

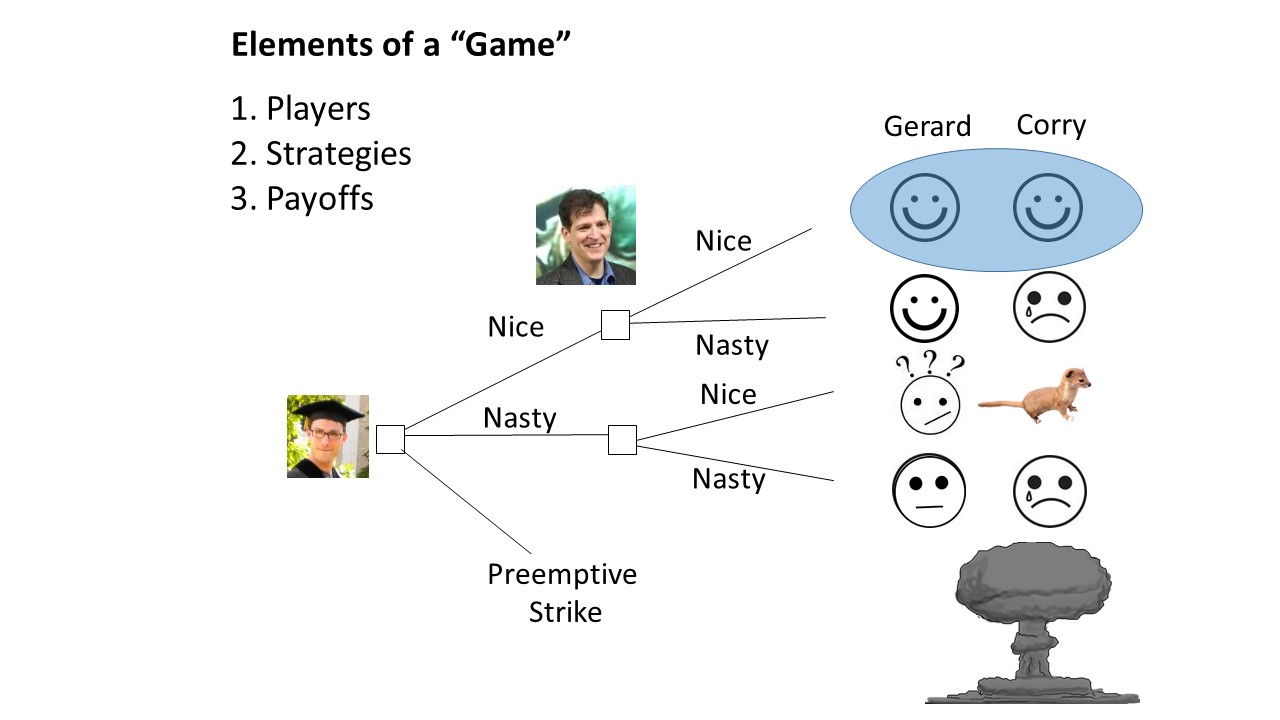

While RAND was initially proud of this work, pride and a haughty spirit often go before a fall. RAND’s patrons in the US Air Force, some of whom were always skeptical of the idea that pencil-necked academics could contribute to military strategy, were apoplectic. RAND had chosen a strategy that would result in high casualties, in part because the objective function had given zero weight to the lives of airplane crews. In itself, this failure to weigh the lives of crews offended the US Air Force brass, many of whom were former pilots.* (Banzhaf 215).

In response, some of the big thinkers at RAND, including legendary UCLA economists Jack Hirshleifer and Armen Alchian, went to work framing the problem.

In our society, personnel lives do have intrinsic value over and above the investment they represent. This value is not directly represented by any dollar figure because, while labor services are bought and sold in our society,human beings are not. Even so, there will be some price range beyond which society will not go to save military lives. In principle, therefore, there is some exchange ratio between human lives and dollars appropriate for the historical context envisioned to any particular systems analysis. Needless to say, we would be on very uncertain ground if we attempted to predict what this exchange ratio should be.

But picking out what the exchange ratio should be is exactly what the Value of Statistical Life is all about. So, eventually, Thomas Schelling picked up on the problem with Ph.D. student Jack Carlson, culminating in Schelling’s 1968 piece, “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” exploring tradeoffs in willingness to pay for reductions in microrisks. According to Banzhaf, Schelling’s contribution was to make the connection between public policy tradeoffs between lives and equipment and individual decisions involving risk (e.g., taking “hazard pay” that provides a premium for taking more dangerous assignments) (Banzhaf 222).

Earlier this term I gave the Freshman Studies lecture on Schelling’s Micromotives and Macrobehavior and spoke extensively about microrisks, though I was not aware of this particular contribution. I guess I will put that incorporate that if I give another talk next year.

References after the break.

* Banzhaf also gives us a taste of public choice to go along with that: “But moreover, that failure led RAND’s program to select cheap propeller bombers rather than the newer turbojets the US Air Force preferred” (215).